Sex, Lies... and a Pulitzer Prize

In 1995 Nigel Jaquiss ’84 left a Wall Street career to take a stab at journalism. This year he was rewarded for his investigative report of a former governor’s indiscretions.

Sept/Oct 2005 DAVID MCKAY WILSONIn 1995 Nigel Jaquiss ’84 left a Wall Street career to take a stab at journalism. This year he was rewarded for his investigative report of a former governor’s indiscretions.

Sept/Oct 2005 DAVID MCKAY WILSONIN 1995 NIGEL JAQUISS '84 LEFT A WALL STREET CAREER TO TAKE A STAB AT JOURNALISM.

THIS YEAR HE WAS REWARDED FOR HIS INVESTIGATIVE REPORT OF A FORMER GOVERNOR'S INDISCRETIONS.

Nigel Jaquiss stood in the grand rotunda at Columbia University's Low Library, mingling with the titans of journalism as light poured in from windows too feet above the polished marble floor. Wearing a dark striped suit that hadn't been out of his closet in eight years, Jaquiss glanced around the room.

"It's all the big guys and Willamette Week" he said. It seems sort of incongruous."

The occasion was the Pulitzer Prize winners' luncheon last May. Jaquiss, a reporter for the 90,000-circulation Week in Portland, Oregon, was on hand to pick up his prize as the first reporter from an alternative weekly to win the coveted journalism honor.

The gala came a year after Jaquiss had written his expose on former Oregon governor Neil Goldschmidt's sexual abuse of his children's babysitter in the 1970s while he was Portland mayor. Through court documents and interviews, Jaquiss pieced together a gripping tale of sex, power and politics that was first published on the weekly's Web site.

For Jaquiss, 42, the award highlights a journalism career that began in the late 1990s after Jaquiss had already enjoyed a successful run on Wall Street as an oil commodities trader. Both of his career choices had unlikely beginnings.

At Dartmouth Jaquiss majored in English and wasn't much good at economics. As a senior he had no clue about a post-graduation career. But he did have a father who promised to pay for a summer trip to Europe if he landed a job before receiving his diploma. So Nigel dutifully interviewed with on-campus recruiters from such disparate employers as the Central Intelligence Agency, the Peace Corps and Cargill, the international agricultural giant. Finally, Jaquiss, who'd worked on farms growing up in Indiana, clicked with the Cargill recruiter. He got the job. He scored the trip to Europe. And in the fall of 1984 he entered Cargill's training program to become a commodities trader.

During the next 11 years, including four in Singapore, he worked in the fast-paced oil market for Cargill, Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs and Greenwich Energy Partners. "Oil trading is a lot like reporting," says Jaquiss. "You spend most of your time on the phone, finding out who knows what, and who is lying. You sit there sucking in information from your computer screen, reading Bloomberg, Reuters. And you place bets, buying North Sea oil, selling it in north Texas or in the Middle East."

Though Jaquiss became adept at predicting the price of a barrel of oil, after a few years he grew dissatisfied, realizing the decision he made his senior year was not a decision he had to live with for the rest of his life. His parents' deaths—he lost his 57-year-old father to a heart attack and his mother was 59 when she died of lung cancer—taught'him, in a very per-dreams are attained.

By then he'd married Meg Remsen '84, whom he'd started dating after paddling together on the Ledyard Canoe Clubs annual Trip to the Sea canoe voyage from Hanover to Long Island Sound their senior year. Their first child, Hannah, was born in 1995.

"I could have stayed in the oil business," says Jaquiss, who now has three children. "It was lucrative, but it wasn't really fulfilling. I decided to test myself and do what I really wanted to do, which was write. I was 33, had a child and some money in the bank. I figured I'd try it for five years."

He consulted with his wife, who'd listened for several years to his grumbling about commodities trading. 'After he'd been in the business for six years, it was like every year, he'd ask me 'Do you think we have enough money saved so I can quit?"' says Remsen. "He kept asking the question, and for years, he kept working. Then, after the birth of Hannah, he decided he didn't want such a high-stress business, though what he ended up doing seems to have more stress."

In 1995 Jaquiss quit Wall Street. He spent six months writing a novel—what he calls a "literary thriller"—based loosely on his experience in the oil-trading world. As with many first novels, publishers didn't bite.

Though he had never written for his high school paper or TheDaily D at Dartmouth, Jaquiss turned to nonfiction. On the suggestion of a journalist friend and classmate, Viva Hardigg '84, he enrolled at Columbia Universitys School of Journalism for a one-year masters program. He studied under Pulitzer-winner James Stewart and fell in love with writing in-depth articles on public affairs.

"He pounded into my head the power of documents, which are the cornerstone of good investigative reporting, says jaquiss. "He also told me the importance of finding an editor who would make you better and force you to improve."

Without a single published story, Jaquiss moved west and found a job at Willamette Week. It's a free weekly that offered Jaquiss a fraction of his Wall Street salary but gave him the opportunity to write magazine-length investigative pieces on a fairly regular basis. Within a few years Jaquiss had received national recognition, winning an award from the Education Writers Association for his investigation of Portlands worst performing middle school. Jaquiss found school officials had known for years that students were subjected to unhealthy levels of radon and toxic mold. The school was closed the day his story appeared and has never reopened.

Results of that magnitude convinced Jaquiss he'd made the right career choice. "In trading, I was acting purely in my own self-in-terest, while in journalism, I'm acting in the public interest," he says. "That sounds corny, perhaps, but it feels like I'm contributing more than just filling my own wallet. Ultimately, there's more psychic reward in delivering something in the public interest.

Jaquiss has made a name in the Northwest as a reporter with keen understanding of the intersection between the forces of the free market and government authorities who have power over economic development. He has detailed the nature of public-private partnerships in Portland and exposed conflicts-of-interests between officials' public duties and their private business dealings. "Nigel can synthesize information and make connections as well as anybody I know," says Willamette Week editor Mark Zusman. "He believes in the value of documents. He'd rather get a source document than an interview. People can lie. Numbers don't.

One of those documents led Jaquiss to his Pulitzer. He found it while researching a story about the business dealings of Goldschmidt, who had been named to the board of a state utility that was seeking to purchase an electric company. During one interview, a state lawmaker told Jaquiss she had part of a document about a rape case involving Goldschmidt's former babysitter.

Jaquiss traveled to Oregon's Washington County to obtain all the court records and then made requests for court records in other Oregon counties. He learned that in 1988 the former babysitter had been assaulted and raped; court documents from that case, which led to the rapists conviction, indicated the victim had been counseled previously for being sexually abused on a regular basis for three years, starting when she was 14.

The records did not name Goldschmidt, but Jaquiss had suspicions. "There never was a 'smoking gun' document, he says. But it jibed with all the stories Id heard."

Jaquiss finally met the victim, then 42, in Las Vegas, hoping she would confirm the abuse: She didn't, unwilling to break a confidentiality agreement she had struck with Goldschmidt when he offered her $350,000, paid out in installments through 2015, after shed hired a lawyer to bring a lawsuit. That left Jaquiss in a difficult position: He had an explosive story about one of Oregon's most powerful figures, but it was based on court documents that didn't name Goldschmidt, and the story was denied by the victim and her mother.

Undeterred, Jaquiss kept pushing, conducting interviews with Portlands political and corporate elite about Goldschimdt's past. He wrote the story, with denials from Goldschmidt and an open spot for his response. A week before its planned publication in the May 12, 2004, edition of the Week Jaquiss placed another call to Goldschmidt's lawyers to tell them it was ready. Goldschmidt then resigned as chairman of the Oregon Board of Higher Education and called a meeting with the editors of The Oregonian, Portlands daily.

Jaquiss caught wind that Goldschmidt had confessed to The Oregonian that he'd had "an affair" with "a high school student." The reporter quickly fashioned a shortened version of his story for the weekly's Web site to avoid being scooped by the daily. A longer version followed a few days later, and in December 2004 Jaquiss wrote an in-depth article that detailed how Goldschmidt s sexual improprieties were kept secret so long. (To read the prize-winning story, go to www.wweek.com/story.php?story=5091.)

Goldschmidt, an attorney, subsequently resigned from the Oregon bar and left his lucrative consulting firm. His portrait was also removed from the walls of the state capitol. Having sex with an underage girl is considered statutory rape, but the statute of limitations had long run out before Jaquiss made public Goldschmidt's relationship with his babysitter. "My story brought justice for the victim," Jaquiss says. "And on a bigger scale, it demonstrated that nobody is above scrutiny, nobody is above the law. A lot of people knew the secret, and it seemed like two standards applied—that powerful and successful people could get away with anything."

The Pulitzer award brought him $10,000 which he'll use to pay his children's school tuition, plus a whirlwind of interviews and speaking engagement offers. A Hollywood screenwriter has purchased the rights to the story and a slew of Oregonians are calling with their tales of personal woe, backroom political machinations and unbridled corporate greed. The Goldschmidt story, after all, is last year's news, and Jaquiss is well aware that his editors want to know what he has cooking for next week.

"I keep trolling for the next good one," says Jaquiss. I'm working on a couple of threads that deal with small municipal misfeasance that could grow into something big. When you are writing about the intersection of public policy and private development, there will always be something there."

Headline News With his wife, Meg, anddaughter Nell lookingon, Jaquiss sheds a tearupon learning he'd wonthe Pulitzer in April.

"In trading, I was acting purely in my own self-interest,while in journalism, I'm acting in the public interest."NIGEL JAQUISS

David McKay Wilson, a New York-based journalist, writes abouteducation for The Journal News in White Plains, New York.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryVoices Crying (and Laughing) in the Wilderness

September | October 2005 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

Feature

FeatureSoviet Union

September | October 2005 By ROBERT SULLIVAN ’75 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYBand of Sisters

September | October 2005 By Maura Kelly ’96 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTENo Quieter Bed

September | October 2005 By James Zug ’91 -

Interview

InterviewThe Archivist

September | October 2005 By Sue DuBois ’05 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

September | October 2005 By BONNIE BARBER

DAVID MCKAY WILSON

-

Feature

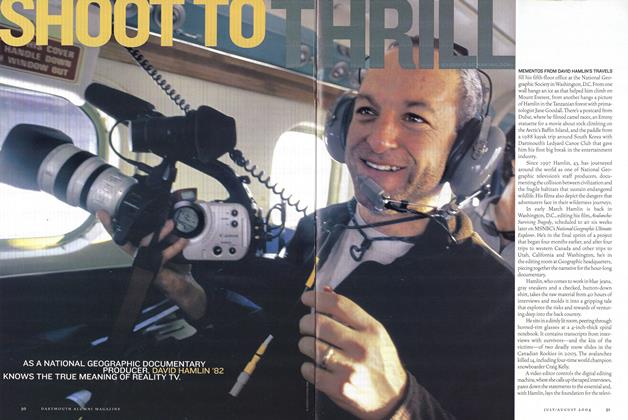

FeatureShoot to Thrill

Jul/Aug 2004 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

Cover Story

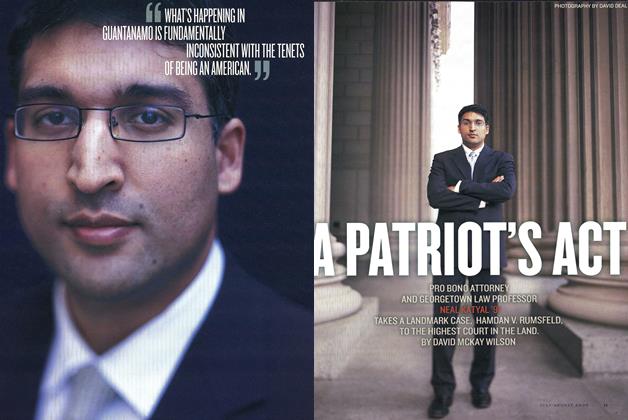

Cover StoryA Patriot’s Act

July/August 2006 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDESea Change

Jan/Feb 2009 By David McKay Wilson -

Feature

FeatureCampbell’s Coup

Jan/Feb 2010 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

SCIENCE

SCIENCEKing Bee

Nov/Dec 2011 By David McKay Wilson -

Sports

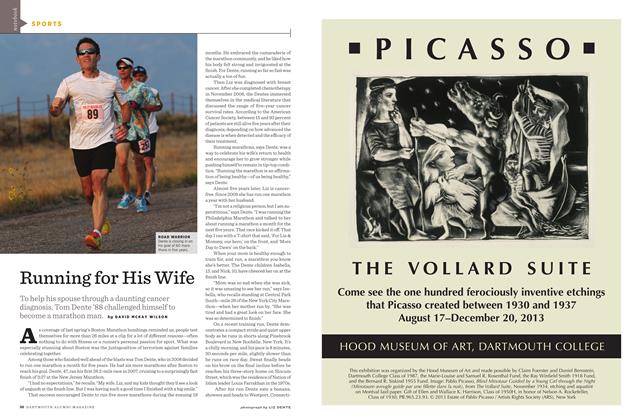

SportsRunning for His Wife

September | October 2013 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON

Features

-

Feature

FeatureClassnotes

JAnuAry | FebruAry By DARTMOUTH COLLEGE LIBRARY -

Feature

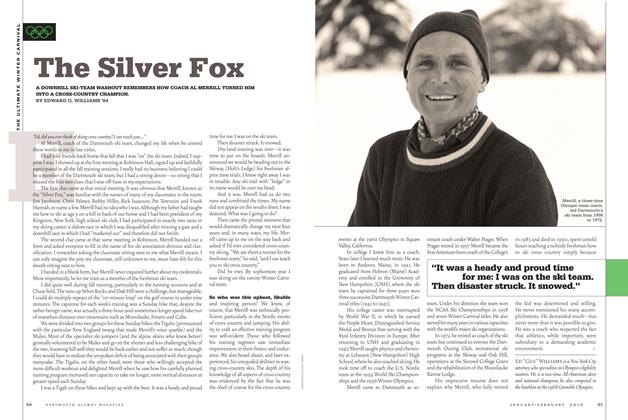

FeatureThe Silver Fox

Jan/Feb 2010 By EDWARD G. WILLIAMS ’64 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPrivy Counselor

MARCH 1995 By Jay Evans '49 -

Feature

FeatureStaying Clear

SEPTEMBER 1996 By Jeanet Hardigg Irwin '80 -

Feature

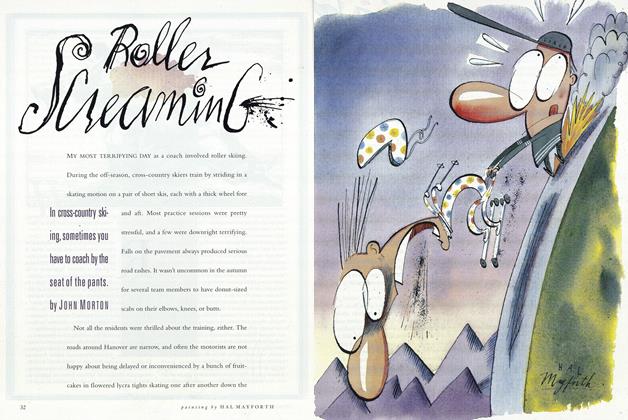

FeatureRoller Screaming

February 1993 By John Morton -

Feature

FeatureOUR PASSIONATE PREFERENCE

FEBRUARY 1991 By Joseph D. Mathewson '55