"The biggest mistake,' Dorothy Day said, "is to play things safe in this life and end up being moral lailures."

IT WAS ATA CONVOCATION ceremony that President John G. Kemeny '22 A welcomed the class of 1976, the first class to which Dartmouth had admitted women as first-year students. I am pleased to announce that the 1997-98 academic year—the year that marks the 25th anniversary of coeducation will be dedicated to his memory.

I want to initiate this celebratory year by talking about an extraordinary woman, Dorothy Day, who spent her rich 83 years straggling to answer the question that lies at the heart of a liberal education: How should I live my life? For Day the question was how to translate her Catholicism into her daily existence. For 47 years, from 1933 until her death in 1980, Day led the Catholic Worker movement-a movement dedicated to bearing living witness to the teachings of Jesus Christ by fighting for social justice.

As founding editor of The Catholic Worker newspaper, Day consistently articulated a vision of cooperative labor, racial and economic equality, decentralized power, and pacifism. But she refused to dwell only in the realm of theory. Committing herself to living with the poor, she resided in the first of many Catholic Worker "hospitality houses" St. Joseph's House on New York's Lower East Side where she and her fellow Catholic Workers offered food, shelter, conversation, and empathy to society's outcasts.

After only two years at the University of Illinois, Day put her formal education behind her. Inspired by the class-conscious writings of jack London and Upton Sinclair, she became a reporter for a Socialist newspaper, The Call. She joined the bohemian world of Greenwich Village, coming to know Max Eastman, Michael Gold, John Reed, Emma Goldman, Margaret Sanger John Dos Passos, Eugene O'Neill, and Hart Crane, with whom she debated art, literature, philosophy, politics, and sexual morality.

In 1927, at the age of 30, she and her common-law husband, an anarchist and atheist, had a daughter. It was a sense of overwhelming joy and gratitude at the birth of her daughter that caused Dorothy Day to join the Catholic Church. It was then, she insisted, that her life truly began. Still, the question remained: How was she to transform Catholicism from ritual and faith into acts that were practical and relevant to the poor?

Peter Maurin, an idealistic social activist, a journalist, and a devout Catholic, persuaded Day to start The Catholic Worker. Funded with $57 scrounged from friends, the monthly tabloid's first edition of 2,500 copies was published on May Day 1933 in Day's tiny tenement apartment and hawked for a penny a copy amid the soapbox speakers and heckling factions of Union Square. By the end of the year circulation had increased to 100,000. Even today, the price of a copy is still a penny, and the editorial policy remains the same: grass-roots Christianity, pacifism, and social justice.

In 1933 Day and Maurin opened St. Joseph's House for the destitute, the hungry, the homeless, and the unemployed. It was the first of many such hospitality houses across the country. Serving at St. Joseph's House fulfilled Dorothy Day's deep yearning to lead an active Christian life. She was suspicious of paternalistic reformers who moralized about the poor and sought to change their behavior. Genuine Christian charity, she believed, came with no strings attached. "Who are we to change anyone," she asked, "and why cannot we leave them to themselves and God?" She was opposed to the welfare bureaucracy, which she saw as impersonal, unsympathetic; and degrading.

It is difficult from the largely secular perspective of our time to grasp the depth and significance of Dorothy Day's faith. Today the religious foreground has largely been claimed by the political right. Day claimed Christianity for the religious left. Whether feeding striking longshoremen on the New York waterfront, joining the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in the fight for voting rights in Mississippi, or standing on picket lines in California with Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers, Day believed that she was supporting the central tenets of Catholicism: radical love, a losing of the self for others, the dignity of labor, voluntary poverty, a shared responsibility for the common good, and a rejection of violence.

As I consider how Dorothy Day chose to live her life, I am struck by the firmness of her convictions as well as by the depth of her faith, by the extent of her self-understanding as weE as by the nature of her compassion for others. "The biggest mistake, sometimes," she once said, "is to play things very safe in this life and end up beingmoral failures."

Dorothy Day never played things safe. She did not attain moral perfection she knew that no human could do that but she did achieve what Willa Cather defined as happiness: "to be dissolved into something complete and great." In answering the question "How should I live my life? " in the way that she did seeking sanctity rather than celebrity, enlarging the boundaries of human love, and choosing to do good rather than to live well Day bore witness to how a life of idealism and character can be lived.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

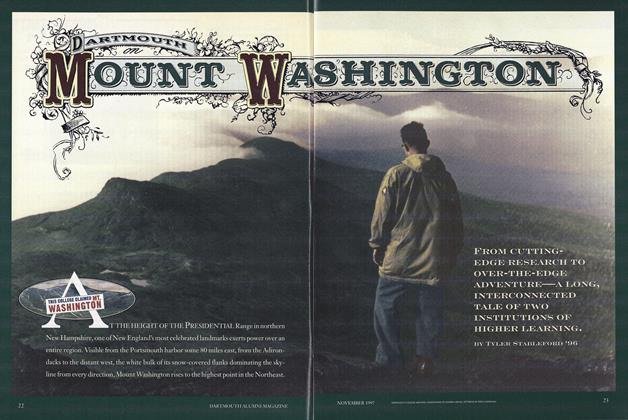

Cover StoryDartmouth on Mount Washington

November 1997 By Tyler Stableford '96 -

Feature

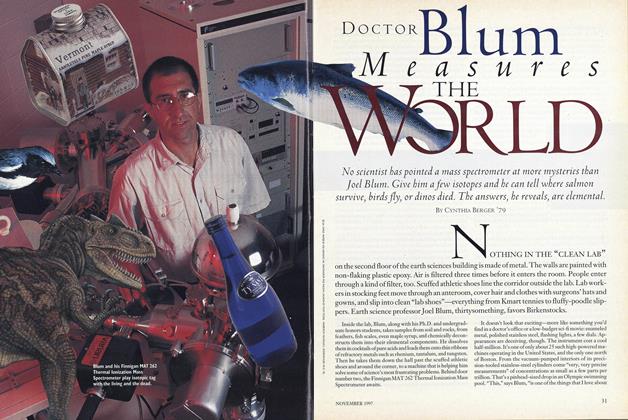

FeatureDoctor Blum Measures the World

November 1997 By Cynthia Berger '79 -

Feature

Feature"Hi. My Name's John. I'm a Zero."

November 1997 By Jeanhee Kim '90 -

Article

ArticleThe Truth, The Half Truth, and Nothing of the Truth

November 1997 -

Article

ArticleThe President Steps Down

November 1997 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleThe Collis Silverware Mystery

November 1997 By Noel Perrin

James O. Freedman

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorPresents Accounted For

June 1994 -

Article

ArticleMY HEROES

MARCH 1991 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleON PERSONAL DISTINCTION

OCTOBER 1991 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe Idealist a Leader

February 1993 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticlePreparing for Contingencies

December 1995 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleStaying Out of the Groove

SEPTEMBER 1997 By James O. Freedman

Article

-

Article

ArticleCONSECRATION OF BISHOP SUMNER

February, 1915 -

Article

Article172nd Commencement

June 1941 -

Article

ArticleHANOVER'S DORMITORY TOWN

May 1962 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20 -

Article

Article1943 Fund Report of Thayer School

January 1944 By F.H.Munkelt '08 -

Article

ArticleSOME OLD DARTMOUTH CUSTOMS

April 1934 By Oscar M. Ruebhausen '34 -

Article

ArticleCharles Proctor

November 1940 By The Editor