"In the end, George Kennan's influence stemmed from his willingness to relinquish the heady satisfactions of power that were his as an insider in order to preserve his moral authority as an outsider."

LAST SEPTEMBER I SPOKE AT Convocation of another of my heroes: George F. Kennan, whose accomplishments as a Russian historian and a principal architect of postwar American foreign policy are especially noteworthy today.

Some of Dartmouth's incoming freshmen undoubtedly found it reassuring to learn that a man who would become such a prominent American intellectual entered Princeton poorly prepared academically (he described himself later as "the last student admitted") and that his academic performance there was undistinguished.

Not knowing what else to do after graduation, he entered the Foreign Service; the State Department immediately sent him overseas. When the United States recognized the Soviet government in 1933, Kennan, not yet 30, accompanied America's first ambassador to Moscow.

During World War II Kennan served in the American embassies in Lisbon and Moscow before returning to the United States as director of the State Department's Policy Planning Staff. From 1946 to 1950, as one of the government's acknowledged experts on Soviet affairs, Kennan engaged in the day-to-day formulation of foreign policy at the most senior levels.

His influence soared with the publication, in July 1947, of his famous "Mr. X" article in the journal Foreign Affairs. The essay, published under the pseudonym X, expressed reservations about resting American foreign policy upon the hope of building trust with the Soviet Union. Arguing that conciliation and appeasement would not work because of Russia's instinctive sense of insecurity and its commitment to world domination, he called for a policy of containment based upon "the adroit and vigilant application of counterforce at a series of constantly shifting geographical and political points." The proposal became the underpinning of the Truman Doctrine, the Marshall Plan, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, and the Berlin airlift. For the next 40 years, containment remained a firm, if controversial, cornerstone of American foreign policy.

Yet Kennan was repelled by the virulence of the anti-communist rhetoric of the Cold War decades and by the headlong acceleration of the nuclear arms race. As he often stated, he preferred to emphasize the importance of following a rational, disciplined foreign policy based upon a recognition of the balance of power and a respect for the zones of vital interest of the contending superpowers.

As could be expected, his criticisms of American foreign policy were not well received in the State Department. Never, perhaps, was Kennan more acutely aware that he was both an insider to the making of foreign policy and an outsider to the foreign-policy establishment than the day in 1953 when Secretary of State John Foster Dulles informed him that, after 27 years, his career in the Foreign Service was at an end.

Having thus been forced to retire at an early age, Kennan embraced scholarship as his principal vocation. He joined the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton, where he wrote more than 20 books, including a history of Soviet-American relations during World War I and his memoirs, for each of which he received a Pulitzer Prize.

During the later decades of his life, Kennan was deeply disturbed by "the obvious deterioration in the quality both of American life itself and of the natural environment in which it had its being, under the impact of a headlong overpopulation, industrialization, commercialization and urbanization of society." Even the exercise of foreign affairs he increasingly found to be, as he wrote, "an empty one; for what use was there, I had to ask, in attempting to protect in its relations to others a society that was clearly failing in its relation to itself?" He scorned the war in Vietnam as a monumental error giving farther evidence of America's moral decadence and intellectual inco mpetence. And he disapproved of what he regarded as the self-indulgent behavior and values of the student left during the turbulent years of the 19605.

Burdened by a growing feeling of intellectual loneliness, Kennan sought "in the interpretation of history a usefulness I could not find in the interpretation of my own time." Adopting the outsider status of a scholar, he conscientiously distanced himself from the immediacy of events precisely so that he could better contribute to understanding them.

In the end, George Kennan's inestimable effectiveness and influence stemmed from his daunting integrity, his refusal to trim his views to fit the fashion of the moment, and his willingness to relinquish the heady satisfactions of power that were his as an insider in order to preserve his moral authority as an outsider.

We live today in a society of self-promotion and networking, a culture obsessed with who's in and who's out, who's hot and who's not, a country mesmerized by the meretricious tinsel of fame. If our society truly cares about excellence, we must celebrate those heroes and heroines who achieve the disciplined dignity of intellectual independence. The life of George F. Kennan provides an elevating example of such heroic achievement.

I hope that all Dartmouth students will identify for themselves persons whose idealism inspires their best effort and whose examples supply them with the strength to stay the course. And I hope, too, that they find Dartmouth College forever a commonwealth of liberal learning that directs their attention to heroic lives and nurtures their growth as wise and humane citizens of this country and the world.

George Kennan

This essay was adapted from the presidents 1991 Convocation address. A useful source was David Mayers's kennan and the Dilemmas of U.S. Foreign Policy.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

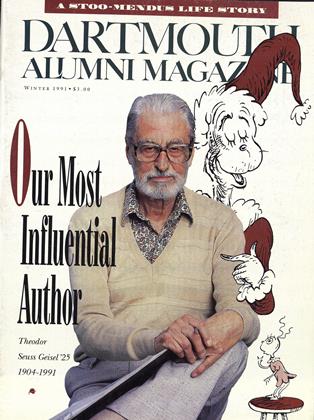

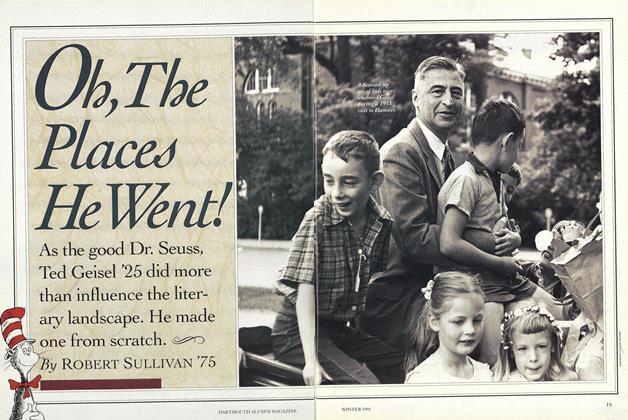

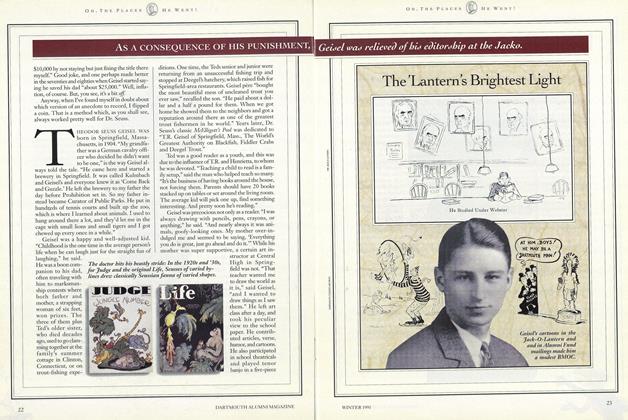

Cover StoryOh, The Places He Went!

December 1991 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

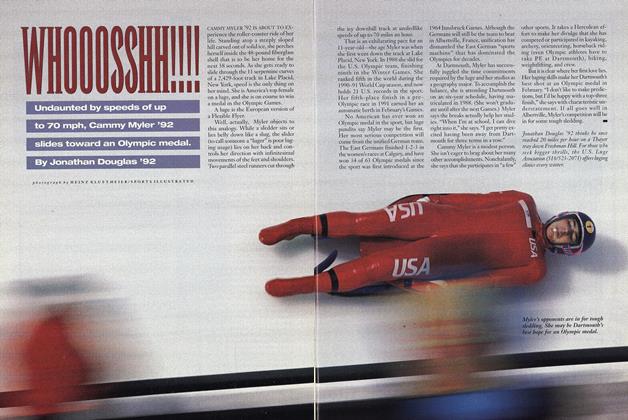

FeatureWHOOOSSHH!!!!

December 1991 By Jonathan Douglas '92 -

Cover Story

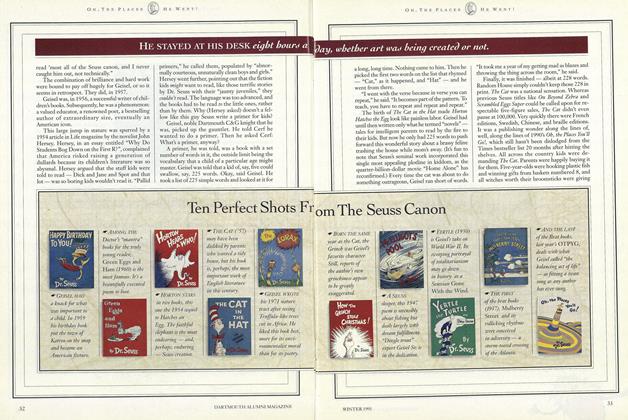

Cover StoryTen Perfect Shots From The Seuss Canon

December 1991 -

Cover Story

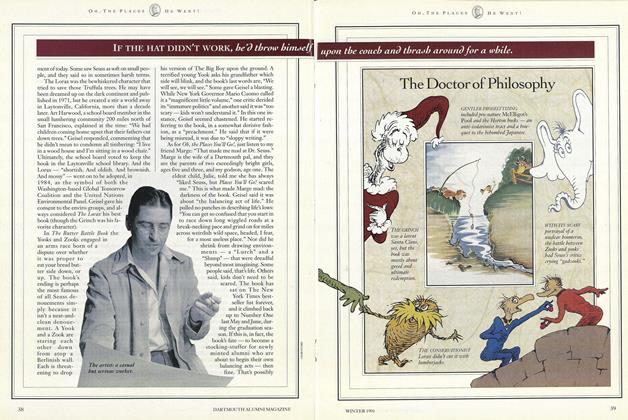

Cover StoryThe Doctor of Philosophy

December 1991 -

Cover Story

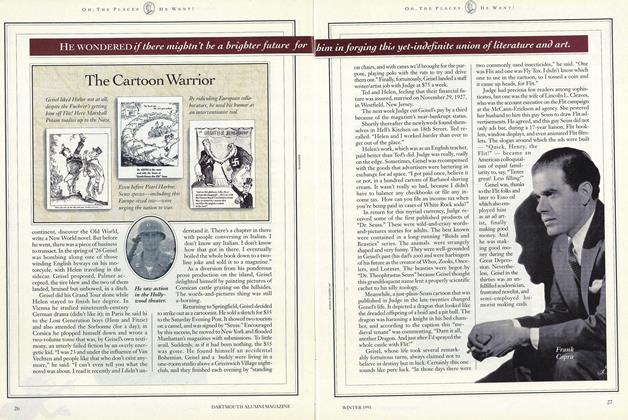

Cover StoryThe Cartoon Warrior

December 1991 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe 'Lanterns' Brightest Light

December 1991

James O. Freedman

-

Article

ArticleCOACHES AND PRESIDENTS

OCTOBER 1990 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleA ROBUST INTELLECTUAL

APRIL 1991 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleA Comprehensive Overhaul

October 1992 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe Idealist a Leader

February 1993 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleWhen Knowledge Cures

October 1995 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe Liberating Arts

MAY 1996 By James O. Freedman