With Russia's first post Soviet presidential election scheduled to take place in June, government Professor Thomas Nichols is challenging conventional academic wisdom that a strong president threatens a developing democracy.

Many experts believe that the successful presidential democracies of the United States and France are exceptions to the rale. After all, look at the post-colonial dictatorships of Latin America. But that theory does little to explain the realities of eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, says Nichols, who is currently on sabbatical to study the origins of Russian presidentialism.

Contrary to the widespread belief that presidential elections can be

Socailly divisive, Nichols contends that presidentialism is the result of social instability, not its cause. A strong leader may in fact help consolidate a democracy, he argues. Separation of powers in a presidential system can add stability by making laws more difficult to pass or repeal. "This is particularly appealing to societies where there is little trust, or where competition between political groups hasn't been institutionalized—which pretty much sums up the former Soviet Union," Nichols says. "If you fear other groups in your own society, the slow and cumbersome nature of a presidential arrangement makes a lot more sense than the rough and tumble of a more unpredictable parliamentary situation."

No matter who triumphs in June, he predicts, the real winner will be democracy.

This art's weightynature buoyed itscampus position.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

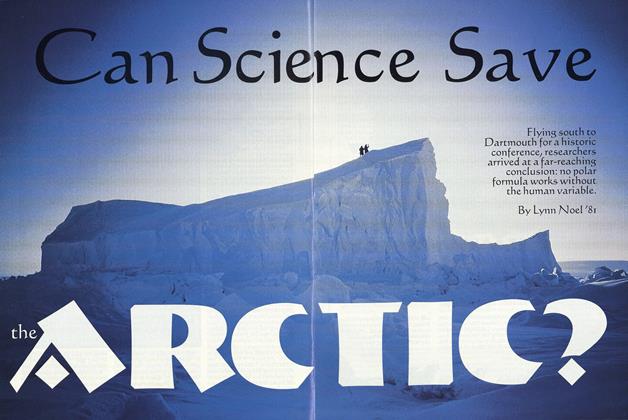

Cover StoryCan Science Save the Arctic?

March 1996 By Lynn Noel '81 -

Feature

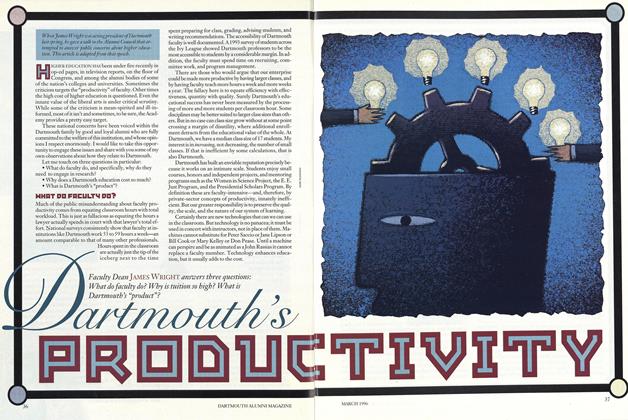

FeatureDartmouth's Productivity

March 1996 By James Wright -

Feature

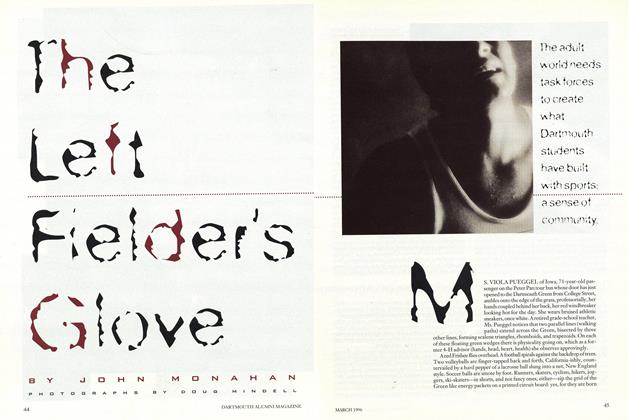

FeatureThe Left Fielder's Glove

March 1996 By JOHN MONAHAN -

Feature

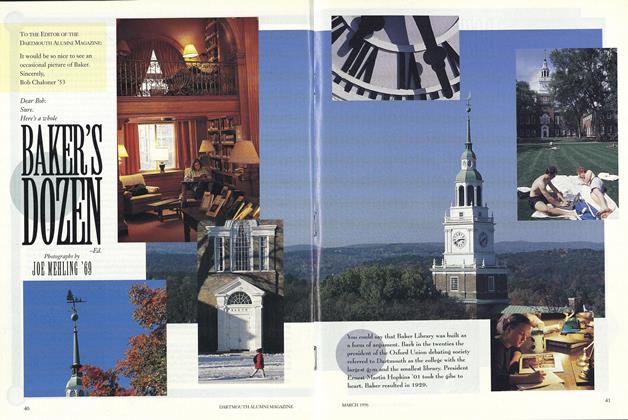

FeatureBAKER'S DOZEN

March 1996 -

Article

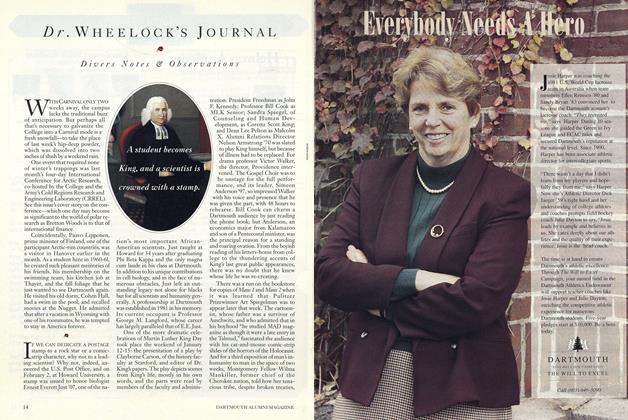

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

March 1996 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleSpace Politics

March 1996 By Karen Endicott