Time was when there were no more exciting words than the countdown to lift off. From the sixties through the early eighties, Americans sat glued to their televisions to witness each blastoff. We were there when Apollo 11 reached the moon, and listened, chilled, to the terrifying suspense of unlucky Apollo 13. We were there for the first Space Shuttle missions, the first space walk. We counted down for Challenger, then watched replay after replay of the explosion. We held our breaths when Shuttle missions resumed two years later. And then many Americans shifted focus. (When was the last time you actually scheduled time to watch a Shuttle launch?) Has space exploration really become so routine that we take it for granted, or is something else going on?

In a freshmen seminar on Space Politics, physics professor Mary Hudson takes students from the earliest Cold War days of the American space program to today's increasing tensions between space aspirations and down-to-earth budget battles. "These students were not even born when Neil Armstrong walked on the moon," she notes. "I try to get them into the present milieu." Hudson has taught the course three times now, with full enrollments. The course tends to attract students who have relatives in the aerospace industry, who have visited the Air and Space Museum, or been to space camp, Hudson notes.

She takes them back to 1957 when the Soviet Union placed the world's first satellite, Sputnik, into orbit. The United States gasped, awed at the scientific achievement the launch represented, horrified that we hadn't done it first. "The United States in the fifties was complacent about being in technological first place. We underestimated the Russians," says Hudson. Armed with Werner von Braun's know-how, the United States had been working on a satellite program since 1955, in anticipation of the 1957-58 International Geophysical Year of scientific cooperation. But there we were, caught with our feet on the ground. Concerned about setting a precedent for overflying other countries with rockets developed by the military, President Eisenhower had stalled in favor of a civilian space program. "The Soviets just did it," Hudson says. But as soon as Sputnik went into orbit, the United States felt pressure to catch up. It rushed the launch of the navy's Vanguard satellite, which failed. Von Braun and the army succeeded with the Explorer satellite in January 1958. Six months later, Eisenhower and Congress created the civilian National Aeronautics and Space Agency, which consolidated rival army, navy, and air force programs and separated out the nation's scientific goals from its military agenda.

The Cold War value of civilian space exploration was not lost on President Kennedy. In 1961, just weeks after the Soviets' Yuri Gagarin became the first human in space, Kennedy announced that we would place a man on the moon before the end of the decade. "It had to be a real leap because we were starting from behind," says Hudson. Kennedy's determination led the nation to pour money and endiusiasm into the resultant Apollo project. "Itwas before the Great Society and Vietnam," Hudson says. "People gave far more than they were paid. People worked overtime because they were excited." Kids across the nation caught the dream, too. "How are we ever going to beat the Russians?" became a rallying cry in high-school science classes.

The science was ultimately responsible for why we won the moon race, says Hudson. While the Russians used heavy fuels, American scientists developed an energyefficient system that used liquid hydrogen and oxygen. American technology had pulled ahead.

Glowing from its lunar success, the United States regarded future manned space travel as a given. NASA's proposal for a reusable shuttle seemed like a viable next step, and President Nixon threw the country's backing behind it. Hudson explains that NASA justified the Shut- Shut-tie's gargantuan expense with the expectation that every space venture would use it. "The Shuttle became our only launch vehicle," she says.

But total dependence, the experts agree, turned out to be a mistake. The Shuttle, which orbits at 500 kilometers above the earth, literally isn't up to some of the space tasks it has to undertake. For example, satellites that must be placed 30,000 kilometers above Earth to achieve the fixed relative position necessary for 24-hour communications require an extra boost. Moreover, says Hudson, "many small satellites don't require putting human life at risk." The very concept of a space shuttle diverted attention from risk to routine. "Just the name itself was a bill of goods," Hudson says. "It's a dangerous business."

The 1986 Challenger disaster tragically proved the point. "NASA had become so blase about dangerous activity because it had assumed that there couldn't possibly be a failure," Hudson asserts. Noting that Challenger was the first glimpse of the space program that many current students had, Hudson splits the class into two groups to study the mission's technical and management sides. The management aspect is a shock for them after learning about the brilliant dedication behind Apollo. The technical side proves equally troubling. "Solid rocket boosters are like strap-on Roman candles. Once you light the fuse, you can't shut it off," Hudson says. Even after post-Challenger modifications—and new procedures whereby anyone in management can stop a launch if a problem is suspected—the Shuttle remains "the same poor design."

Moreover, Hudson says, many scientific projects suffer from poor design because they had to be made to fit into the Shuttle's cargo bay; before the Shuttle, launch vehicles were designed to fit the payload, not vice versa. What's worse, the scientific community was forced to delay several projects, including its planetary explorations, during the two years the Shuttle was grounded. The Galileo probe that flew past Jupiter in December, for example, originally had been scheduled for launch in 1986. Not until 1989 were Earth and Jupiter again in proper alignment. Then there was NASA's Hubble Telescope, with its faulty mirror, forcing Shuttle astronauts to make an expensive—but spectacular—house call in space. Says Hudson, "NASA turned disaster into a thing they tout—that astronauts can go up and fix things."

Still, NASA—like the American public—knows it can no longer afford to take public support for granted. The long-envisioned Space Station, for example is, Hudson says, "a mission in search of a raison d'etre." The cost for such a project makes less and less sense, given that we are no longer competing with the Russians, whose Mir space station has been in orbit since 1986. "We both emptied our bank accounts in the Cold War," she says.

But it's hard to keep space dreams down. Ending her class with the question "Should we go to Mars?" Hudson gets her answer: "They're ready to go into training programs and do it."

What goes up not always should.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

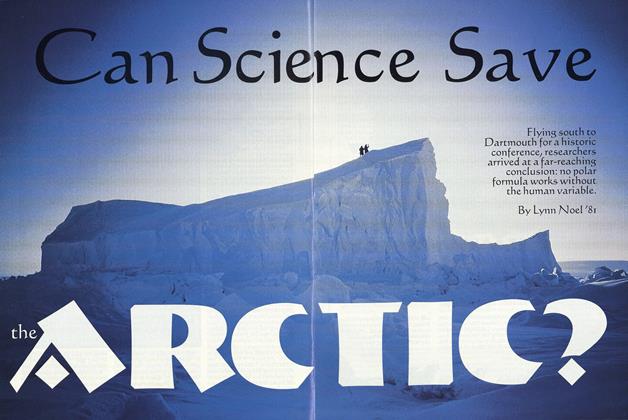

Cover StoryCan Science Save the Arctic?

March 1996 By Lynn Noel '81 -

Feature

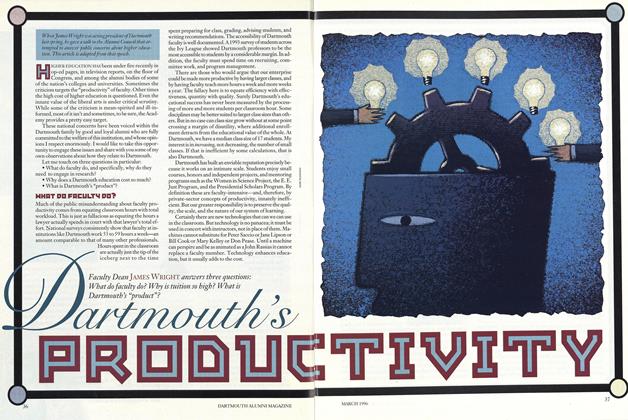

FeatureDartmouth's Productivity

March 1996 By James Wright -

Feature

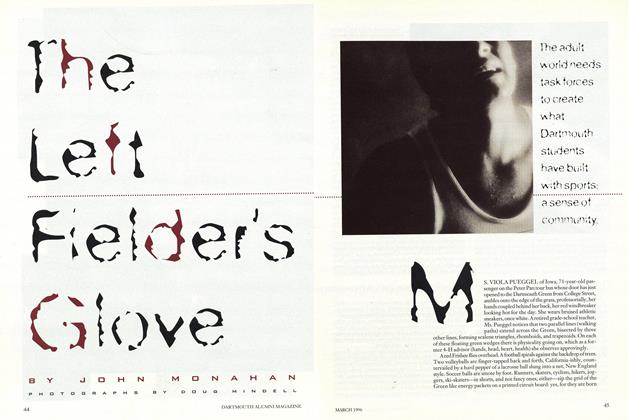

FeatureThe Left Fielder's Glove

March 1996 By JOHN MONAHAN -

Feature

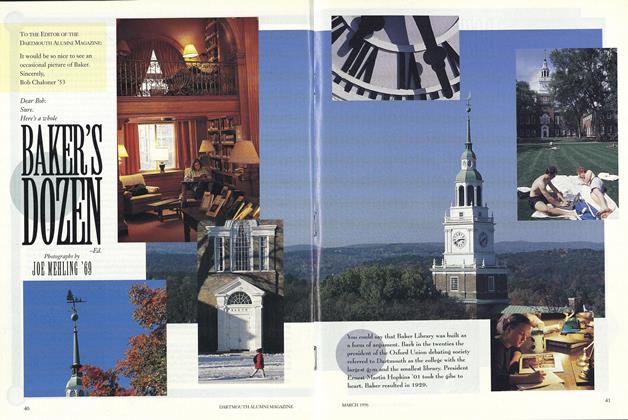

FeatureBAKER'S DOZEN

March 1996 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

March 1996 By "E. Wheelock" -

Class Notes

Class Notes1984

March 1996 By Armanda Iorio

Karen Endicott

-

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

MAY • 1988 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleDaedalus with a Power Glove

OCTOBER 1994 By Karen Endicott -

Article

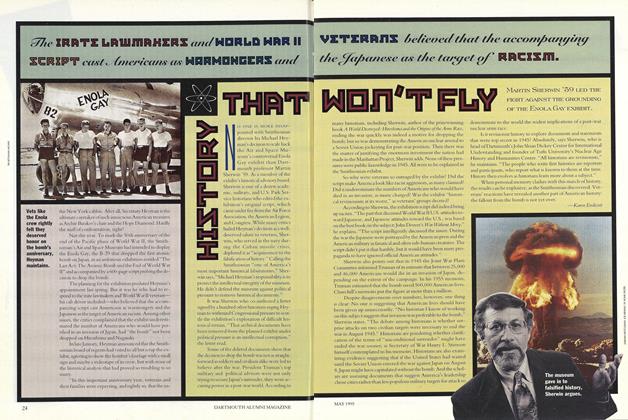

ArticleHISTORY THAT WON'T FLY

May 1995 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleCopper Crown

October 1995 By Karen Endicott -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMWhy the Play’s Still the Thing

May/June 2001 By Karen Endicott -

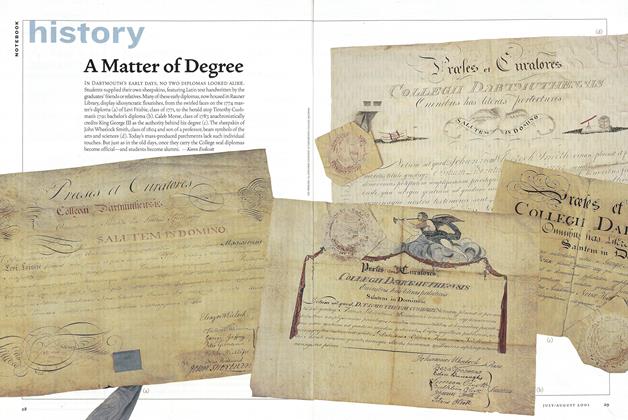

HISTORY

HISTORYA Matter of Degree

July/August 2001 By Karen Endicott