The academy once showed how to separate the great from the mere mortal. Now the emphasis is on the student, and the object is 'Visual literacy'

THE three-year-old at Dartmouth's Hood Museum of Art is unintimidated by the display the Lathrop Gallery. She strides among towering fern figures and slit drums from the Pacific Island nation of Vanuatu. "They like me," she pronounces. She turns a corner into a suite of galleries hung with twentieth-century art and fixes her gaze 011 a large painting. That's... She pauses and statesjudicially: "orange."

From the mouths of babes. Le mot just, thinks a benighted adult standing nearby. The work, Ellsworth Kelly s 1987 print Untitled (Orange), is, uh, an orange shape on a white background. It is big. Child and adult hightail it to the Native-American exhibit.

Louise Hamlin, a painter and professor in Dartmouth's studio art department, shows no surprise. "People go through museums like they go through magazines, she notes. "They get into their museum stroll"—she demonstrates the familiar saunter—"and pass each piece. And they usually only see the most superficial thing about a work, generally its subject matter."Hamlin and most other art educators believe that museum browsers deny themselves one of art's great benefits: its ability to slow down our visual apparatus, to make us see the world with new understanding.

Art clearly has much in common with the rest of the liberal arts—whose central purpose, when you think about it, is to increase one's attention span. There was a time when art education, like the liberal arts in general, existed mainly to put the finish on gentlefolk. Art courses handed down the canon and fostered "taste"—discrimination between great and mediocre, between genius and scribbling. There are professors still, at Dartmouth and at other colleges, who see value in conveying genius. But most faculty today—even those who tout the "greats"—-will tell you there are many other skills for happy lingering in front of an Untitled(Orange); there are many ways to "teach art," and there are few better places for viewing these many ways than at Dartmouth's ten-year-old Hood Museum.

MOST PROFESSORS will also tell you that the need for slowing-down skills has never been greater. "I call it 'remote-control ditto syndrome,'" says Victor Walker, a drama professor who has taken students to the Hood as part of his course on the image of the African American in popular culture. "Because we live in this MTV age, our younger people are accustomed to visual and sound bites, to a medium where the average image lasts 1.3 seconds. To place themselves in a position where they stand there and engage themselves in apiece of art is like, 'What?'" he says, mimicking their disbelief. "To them it's like asking them to write a 50page term paper in a week.'

"We're bombarded by visuals, and we use our visual skills to navigate our world," observes Lesley Wellman, Hood curator of education. "But people rarely are taught a more detailed, analytic approach to looking. Our society was not set up for us to spend a lot of time with these images, so people often don't get to the point of going through layers and layers and figuring out what visual clues mean."

As for how to get through those layers, one might start with the basic tool called the Inquiry Method, developed by museum educators working primarily with children and young adults. Inquiry is a mainstay of the Hood's museum-education program, which oversees 12,000 visits a year from Hanover-area schoolchildren and their families. Wellman demonstrates the difference between this method and the standard mini-lecture a docent might give. She stands in front of a Vanuatu slit drum that dominates the entrance to the Lathrop Gallery. "Now, with the Lecture Method, I might tell you this is a slit gong drum from Vanuatu, formerly the New Hebrides, probably created early in this century, so many feet tall, and it's a musical instrument but probably also represents ancestors," says Wellman, counting her points on her fingers. "I've just shared six facts. If I walk away, you might remember three, because it's really hard to retain facts unless you have a frame of reference. If you've just been studying Oceanic art, what I said would make sense to you. But for the average visistor—who probably doesn't even know what 'Oceanic' means—I just recited six facts that they may or may not retain. But I haven't taught them any skills. So now if I disappeared into thin air, and they turned to the next object, they would be waiting for someone to tell them the next six facts.

The Inquiry Method, by contrast, is built on asking visitors to use their eyes. "The first question I'd ask is 'What do you see?' They might say, 'lt's really tall.' 'How tall? I'm five-footsix and I'm standing next to it. How tall do you think it is? Oh, at least 12 feet tall. What else do you see?' 'I see a face.' 'How do you know it's a face?' 'Well, there are the eyes, the nose, the mouth.' What's just happened by asking 'What do you see?' 'What else do you see?' 'How do you know?' is that the visual evidence is there and the people are doing the looking and figuring it out for themselves." After a period of such direct observation, Wellman might encourage her charges to compare the slit drum with another work of art, such as the Kandinsky in the next gallery, and note what is similar or different about the two. Or she might ask them to guess something about how, when, or by what sort of people a piece was made, or with what materials, or how it might have been used—all before looking at the label to see how well they guessed.

What is taking place seems simple on the surface but can profoundly shift the underpinnings of the experience. Visitors are learning what they can see on their own, and how the knowledge they walked in the door with can help them decipher art. A museum changes from a place where someone else has all the answers, to one where the visitor knows things, or knows how to discover them. It is a quiet sort of radicalism, intent on throwing open A museum doors to those who have felt them closed because of class or educational background. "One of the things we're trying to do in museum education is empower people to feel comfortable using museums as resources," says Wellman. "You can come to a museum and learn about all different people, all different periods, all different cultures. Museums offer a way to travel, intellectually and emotionally. You also can learn more about yourselfwhy do I like one thing and not another?' Who needs this empowerment? Try the typical Dartmouth student. Three years ago, senior James Bloom '93 did a formal study of why relatively few students came to the Hood. One oft-cited reason: intimidation. Many students expressed fear of museums. They were afraid people would come up and ask them questions. They conveyed the sense that art museums divided people into insiders and outsiders and that they themselves, Ivy League students, the creme de la creme of the American educational system, were among the outsiders.

THIS INTIMIDATION APPEARS to be a legacy of the arthistory tradition, which got its start among American universities a century ago. The discipline first entered higher education as a taxonomy of art styles, and as a means of separating the artistic wheat from the chaff, and the insiders from the outsiders. Art theorists developed A sets of formal criteria based on artistic elements in order to allow a ranking of the premier examples of each style. By definition, some schools of art gained much attention, others were overlooked; some artists were deemed important, others were ignored. And Formalism the creed that art should be judged only by its formal, aesthetic characteristics—ruled.

This mode of art history had its problems. Its apparent susceptibility to corruption was one. Declaring an artist to important just happened to inflate the market value of that artist s work, and some of the top critics were selling the stuff. Bernard Berenson, the world's leading expert on the Italian Renaissance at the turn of the century, was dealing in the same art whose value he was helping to drive up.

Attacks against Formalism heated up in the 19305, when Marxist art historians charged that the method was "bourgeois mystification." Over the following decades, increasing numbers of critics took issue not only with Formalism as a set of aesthetic criteria but with the whole notion of evaluating art aesthetically.

While Formalism has gone to the junkyard of ideas, some feel it should be kept for parts. Art history professor Robert McGrath, who has taught at Dartmouth since 1963, still believes in drawing students' attention to what he considers great art; but he avoids any claim of an absolute standard. "When I was being educated and coming up through the academy, we had what we thought was a pretty firm fix on value and quality,' McGrath says. Quality was essentially what people with power and knowledge said it was, people like myself. That's the way everything is done in the world—there is no absolute truth, there are these agreements among people with power, authority, knowledge, who achieve a kind of consensus, what we call an interim truth. Rembrandt is considered great. Rembrandt will be great as long as those of us who possess those criteria still exist, and people still believe us. Still, he sees a need to understand art's formal elements and how a work fits into the evolution of artistic styles and techniques. "When Michael Jordan goes up in the air and spins three times and slam-dunks the basketball, everyone can see that, and they recognize an act that nobody else could do. When Cezanne represents Mont Ste.-Victoire in a way that no one before or after him has been able to do, it's harder to recognize. Everyone who goes to basketball games recognizes the significance of a slam dunk. Not everyone who goes to a museum recognizes that Cezanne represents the culmination of certain kinds of formal investigations that have been going on for a long time in art." McGrath feels that this ability to distinguish is central to an education. "Life is about making choices, it's about evaluating things. I would argue in a moment of sentimental weakness—I rarely would do this before my students that art does enrich one's life, the aesthetic experience, the ability to enjoy the Beautiful. It's a constantly transforming experience. Taste is a curious phenomenon. It's like a pearl necklace. You have to go through each step in order to acquire certain tastes. To use a very crude analogy, you don't go from Coca-Cola to dry martinis without passing through sherry and vermouth. Good taste—and there are "those who would challenge any such notion the ability to surround yourself with, to experience beautiful things, is a wonderfully enriching thing." McGrath hastens to add that art history—his own courses included—teaches other things as well. "It's an intellectual discipline, it's cultural history, it s social history, it'sa good humanist discipline."

The other things get far more attention from art historians today. One of the newest and youngest members of Dartmouth's art-history department, Adrian Randolph, shares with McGrath an expertise in Renaissance art. But Randolph is uninterested in taste. "I think you can make someone like anything," he says. "People attempt to create social ties by liking certain things. If you go to museums, like a certain kind of art, you're making a statement about who you feel similar to. Reactions are certainly very tractable, because how else can you explain that the nineteenth century didn't care about Botticelli until someone discovered that Botticelli was the center of the universe in fifteenth-century painting? It's only because certain people promote an image of what is good or bad; that's how taste fluctuates throughout history."

Instead of taste, art historians are focusing on more tangible, critical skills. For example, when visiting assistant professor Jane Carroll gives a lecture on a luminous eleventh-century German manuscript, she does not focus on its beauty as an art object. She talks instead about the central figure of Christ in the piece. She explains that the Holy Roman Emperor was thought to be Christ's representative on Earth. Unlike most images of Jesus during that period, the Christ in the manuscript looks imperial, with a shaven face and royally purple garb. "We look at this image of Christ and we know right away we're being told he's important, he's all powerful, he connects directly to us, everybody else is subservient to him, and that's all there in the composition and the colors and the way they're presented," Carroll says later. She does not expect students to walk away remembering the manuscript for the rest of their lives. Instead, she hopes that "they come away understanding that wherever they go they are aware that visual images send a message to us, unconsciously sometimes, and I hope they remember enough to try to decode images."

"VISUAL LITERACY" is the phrase you hear most from art educators. Timothy Rub, the Hood Museum's director, thinks it is crucial. "If the institution is committed to preparing students to understand the world critically, wouldn't you want your students equipped to understand images, what they mean, how they work, what messages they contain, and how they convey them? You need to think of this as important as understanding a text or solving a quadratric equation.

Carroll and Randolph agree. They would like to see art history become more of a study of visual culture as a whole, or to at least be more mindful of the cultural context of the objects it studies. A side effect of this broadening of art education toward general culture study is a blurring of the lines between art history and anthropology. The Hood has been a key site for shifting well-worn boundaries between art objets and "material culture, "including historical, archaeological, and ethnographic artifacts. Before the creation of the Hood, Dartmouth housed its collection of "fine" art in Carpenter Hall while Wilson Hall was home to the anthropological/archeological collection, a potpourri of prehistoric pot shards, everyday and ceremonial objects from non-Western societies, and such eerie items as a child mummy. The Hood now houses the two collections, redefining many of the former Wilson Hall objects as "ethnographic art."

This change has not sat easily with all the anthropologists and archeologists. qSome professors grumble about the white-glove treatment that an art museum is obligated to give its objects. "We had some shrunken heads from South America that we would bring into class," remembers anthropology professor Kirk Endicott. "Now they can't leave the museum." Actually, the Hood is better than most in allowing access to objects. A student who wants to see a piece up close can have it brought out of storage for private viewing. Classics professor Jeremy Rutter notes that research projects by undergraduates have beefed up previously scanty information on the museum's Roman coins and other ancient Mediterranean objects. Students poring over a tired-looking pot in storage discovered it had been painted by a noted Grecian artist in the fifth century B.C. They worked with the Hood to have the pot cleaned, restored, and photographed. It is now on permanent display in the Hood's Kim Gallery.

Some lingering friction between art historians and anthropologists lies in the very definition of art. "We would define art as a very unusual category of material culture, one that almost ostentatiously has no practical use," says Endicott, speaking for anthropologists. "There actually are few societies that have anything analogous to fine art. The idea of a totally nonfunctional object that is to be contemplated for its aesthetic qualities is a very Western idea." On the other hand, non-Western objects combine the functional with the spiritual and aesthetic. The Hood's large collection of Oceanic art (art from the Pacific Islands) offers thousands of examples. In each piece there is a tension between the individual artist's style and use of the vocabulary of symbols the artist has acquired from the culture. "If you carved an image of a cult figure, certain things had to be there," explains Tamara Northern, curator of the Hood's ethnographic collection. "If they weren't there, the intended functionality of the object, to protect or help you in some way, would bejeopardized." Anthropologists and archeologists join with many art historians when they look at objects as iconography—visual attributes that communicate about a culture. "If you look at a work of ethnographic art and you only think of how it was used—that's the famous anthropologist's question—you haven't asked why it looks a given way," says Northern. "If you don't know that, you can't make the leap from the age you see to its cultural context." Take the ancient Roman habit of cutting images of the emperor off at the neck. Modem coins still follow this tradition. The bodies of Roman statues would be made separately from the heads. When the emperor changed, the sculptor would simply stick on a new head. This practice departed from Greek statuary, in which the head was an integral part of the body. "The Greeks thought the body to be part of a person's identity," says classicist Jeremy Rutter. "The Romans—the body is irrelevent, it's the head that important. That's culture." We see culture also in the prominent navels of the Hood's New Guinea ancestor boards, depicting the power associated with that part of the body. The face on each board, on the other hand, represents a specific ancestor—a way of extending memory across the generations, as we would use a photograph of our great-grandparents.

ALL THIS TALK about getting at what lies beneath art threatens to obscure what goes on at the surface of a piece. Painter Louise Hamlin is most moved by observing what the artist did with the material. "How does a piece look?" asks Hamlin. "Is the paint smooth or bumpy or thin or thick? Was it put down with precision or with gusto? When you're looking at a Vermeer you know it's different than a de Kooning even though you're not thinking about the differences between seventeenth-century Dutch painting and twentieth-century American painting. It's how the two paintings are different in a physical sense. One, the Vermeer, has a quality of stillness, an unfussy precision. The other has an exuberance and luscious color. Looking at such varied works informs the eye and broadens the senses, she says. "It can influence your life as importantly as any cultural theory." Which, of course, brings us back to a central tenet of Formalism: that what you need for responding to a work of art is in the work itself.

Arguments about how to approach art and objects cannot help but benefit the student. In fact, the Hood staff is working to make the Hood a classroom for literature, history, math, and science, using the collection to benefit disciplines beyond the traditional constituencies of visual studies, art history, anthropology, and the classics. Fellowships funded by a Mellon Foundation grant allow faculty to spend teaching-free time getting to know the Hood collection. The museum's Harrington Gallery is set aside for exhibits that relate to specific classes, and the Hood staff attempts to time other exhibits to coincide with related classes. Faculty and students have collaborated with Hood curators on a long list of exhibits outside the Harrington Gallery, and five students are chosen for year-long internships at the museum to work with curators.

A recent visitor heard the whispers of conversation between disciplines when she asked director Rub for some clues about Untitled (Orange). The painting was part of a show that Rub himself had curated as the museum's chief specialist on twentieth-century art. The show represented prints the Hood had collected in the past decade to add to its already extensive collection. The Orange artist, Ellsworth Kelly, was an important figure in post-war American art, Rub explains. One of a generation of minimalists who emerged in the late 1950s and early '6os, Kelly wanted to "reduce the perceived world to a series of simple, quite elegant geometric forms and fields of usually unmodulated, pure color. I think that one important thing that happened in modern art starting early in the twentieth century was the development of pure abstraction, in which art is relieved of its descriptive function and can express certain values, ideas, feelings in purely abstract form, using the means available to the artist in which pure line, pure shape, pure color—in which various compositional features, the slant of a line, the tilt of an arc in a certain direction—become the very meaning. It is purely abstract the way music is abstract. And that is a dominant theme in twentieth-century art." Rub goes on to point out, stroke by stroke, line by line, arc by arc, the composition of Orange.

A few weeks later, at the behest of the three-year-old, the visitor sits on her living room floor, playing with flat plastic pieces of varying geometric forms and contrasting colors. Too much blue there," she thinks, shifting the pieces around. "Some smaller pieces here. Less obvious symmetry." The three-year-old makes her own decisions. They play for almost an hour. The phrases "pure form" and "relieved of its descriptive functions' float into the woman's consciousness. "Ellsworth, you gem, you absolute mensch," she thinks, reaching for another orange triangle. Given a clue, a conceptual tool or two, who could fail to fall in love with pure abstraction?

To a three-year-old, Ellsworth Kelly's Untitled (Orange) is very...orange.

The Hood is a center for White Mountain art, including Regis Gignoux's composite view.

Jerry Lathrop

In 1963 Edward Joseph Ruscha mythologized Route 66 with his Standard Station,Amarillo, Texas.

Reliquary figure crafted in nineteenth-century Gabon by the Obamba people. Curators now recognize artifacts as art.

Yves Klein wanted to "see...what was visible of the absolute" when he painted this Hood piece.

The African power emblem shows why "people think some objects have magical powers," says anthro's Endicott.

Thom Betterton '94 paints Sol LeWitt's art.

Drama prof Victor Waiker took his class to the Hood to see AfricanAmerican painter Romare Howard Bearden's collage.

Metcalf's TheFirst Thaw is afavorite newacquisition ofthe Hood's Rub.

The FranklinFamilyCollection ofOceanic Art isone of theworld's largest.

Dartmouth artist Esme Thompson calls Terry Winters's use of paint "sensuous."

A standout Hood Western is Frederic Remington's luminous ShotgunHospitality.

August Lopez '97 co-curated NativeAmerican art.

Elecizar is to Green cultists what this gope is to New Guineans.

A Scratch Museum The single most important inspiration for a Dartmouth art museum was Churchill "ierry" Lathrop, who joined the art-history faculty in 1929 and became head of the College collections, such as they in 1935. He took charge of ail of 200 pieces. Lathrop increased the holdings more than a hundredfold, adding the College's first contemporaryart, non-Western art—and prints, which Lathrop had the foresight to collect before they became worth a tortune. Among his many adoring students was young Nelson Rockefeller'30, who gained a lifelong passion for (and awesome collection of) modern art. lathrop died last December.

Poise 'n the Hood The Hood Museum's architect, Charles Moore, started out with a contract but no site. There were several possibilities, none of them ideal. Moore worked with a committee of 30 people from the College to decide where to put the building. The final choice created an even bigger problem: How to use an oddly shaped space between Romanesque Wilson Hall and the 1960s modernist, inyour-face Hopkins Center. Moore's solution, a brick, sweetly domed building tucked way back from Wheelock Street, seems to exist in the fourth dimension. It is hard to find even when you stand in front of it; then it opens up like a pop-up book when you walk through the entrance. Awarded numerous prizes when it first opened, the building is considered one of Moore's best.

Musing On-Line It is four o'clock in the morning, prime studying time, and an art-bistory student has a term paper due when the sun comes up. Desperately needing a quick visit to Picasso's blue period, he does not fling himself weeping on locked library doors. Instead, he mouseclicks from his room into Dartmouth-created software called Artemisia to zero in on images from art-history lectures. The Hood staff is digitizing some of its own holdings, including works by Joan Miro, Max Ernst, and Wassily Kandinsky. Armed with a color Mac rather than a shovel, an archaeology student con even dig up images of 150 of the ancient coins from the museum's collection. The UltimatePaint-by-Number Artist Sol LeWitt designed this 1990 mural covering a whole wall at the Hood. But others did the actual pointing, including Thorn Betterton '91 and Torin Porter '93. The title gave instructions: A wall divided into 3 equal vertical sections / the left and right sections: divided into 15 horizontal bands ofequal width / the middle section divided into 12 vertical bands of equalwidth i each band received a combination of 3 of 4 possible colors / the colorsbeing yellow, red, blue and grey. The method recalls the great Renaissance studios. The idea, not the hand, "becomes the machine that makes the art," says LeWitt.

Name Dropping The Hood Museum's 60,000 pieces include works by Pablo Picasso, Joan Miro, Frederic Remington, John Singleton Copley, Francisco Jose de Goya, Georgia O'Keeffe, Alfred Stieglitz, Edgar Degas, Edouard Manet, Eugene Delacroix, Frank Stella, Rembrandt, Ansel Adams, Jose Clemente Orozco, Andy Warhol, Christo, Frederick Church, Wassily Kandinsky, James Whistler, Joseph Turner, Edward Hopper, David Hockney, Mark Rothko, Albert Bierstadt, Albrecht Durer, Paul Cezanne, Thomas Eakins, Paul Gauguin, George Inness, Paul Klee, Henri Matisse, Amedeo Modigliani, Louise Nevelson, Katherine Porter, Paul Revere, John Singer Sargent, Gilbert Stuart, Jacques Lipschitz, Emil Nolde, Paul Cadmus, George Braque, Mary Cassatt, Max Ernst, Samuel F.B. Morse, Maxfield Parrish, Auguste Rodin, and Edouard Vuillard. Dartmouth alumni represented in the collection include Paul Sample '21, Theodor Geisel '25, Ralph Steiner '20, Bruce Beasley '61, Thomas George '40, Peter Michael Gish '49, Ethan Allen Greenwood 1806, Albert Gallatin Hoit 1829, and Joseph Steward 1780. The Hood has works by such Dartmouth faculty as Varujan Boghosian, Matthew Wysocki, Richprd Ellis Wagner, and Ben S. Moss. To name just a few.

Cool Stuff fromAround the World In addition to being a museum.for art—both Western and non-Western the Hood is also the repository for the College's anthropological and historical collections. : Oceania (Pacific islands) Number of objects: 1,826 Cool stuff dog's teeth necklace, octopus lure, grass skutsNative North America Number of objects: 2,081 Cool stuff: stone vases, arrowheads, bag of oyster shells Native South American Number of objects: 105 Cool stuff: ear of corn, human effigy whistle blowgun Native Central American Number of objects: 280 Cool stuff jar with monkey handles, spindle whorl, stone armadillo Inuit Number of objects: 1,098 Cool stuff: walrus bristles caribou: hoof snow goggles, container made of whale stomach AfricaNumber of objects 938Cool stuff, clove dish rhinoceroshide whip belly har p, cigarettes Egypt Number of objects: 150Cool stuff, mummy mummy pillow, scarabs GreekNumber of objects 158 Cool stuff: first-century A. D. lamp With gladiator's armor design; casts of seals and gems from 300 B.C.300 A.D., amphora Asian Number of objects: 950 Cool stuff: cowrie shell from the Nicobar Islands, Chinese bamboo pillow, Chinese shadow puppets, Burmese jungle-creeper bean Australia Number of objects: 64 Cool stuff boomerangs, stone tools. emu-feather shoes EuropeNumber of objects 909 Cool stuff: a piece from Captain Cook's ship, mosaic fragments from Adrian's Villa, ashes from Pompeii

Who Said That? Match the wisdom with the sage. 1. "We need religion for religion's sake, morality for morality's sake, art for art's sake." 2. "One picture is worth a thou sand words." 3. "Life is short, the art long..." 4. "But the Devil whoops, as he whooped of old: 'It's clever, but is it Art?'" 5. "The greatness of art is not to find what is common but what is unique." 6. "Every genuine work of art has as much reason for being as the earth and the sun." 7. "There are more valid facts and details in works of art than there are in history books." 8. "The first virtue of a painting is to be a feast for the eyes." 9. "Painting isn't an aesthetic operation; it's a form of magic designed as a mediator between this strange hostile world and us, a way of seizing the power by giving form to our terrors as well as our desires." a. Hippocrates b. Isaac Bashevis Singer c. Charlie Chaplin d. Pablo Picasso e. Chinese proverb f. Ralph Waldo Emerson g. Rudyard Kipling h. Victor Cousin i. Eugene Delacroix Charlie Chaplinwas not silent when the subject was art. What did he say? Answers:6-f 1-h 7-c 2-e 8-i 3-a 9-d 4-g 5-b

HangingSpecial exhibitions can "literallyhelp redefine the configurationof a period," says art historyprofessor Robert McGrath.They're also a lot of work. TheHood's solution: students.McGrath and the museum firstbrought in an art-history class tohelp write the catalog for anexhibition on White Mountain artin 1988. Since then studentshave helped curate a dozenmore exhibitions, ranging fromancient sculptures to a recentshow of contemporary Native American self-images. In 1992Kathleen Merrill '92 went a stepfurther, solely curating an exhibition onlandscape paintings as a senior fellowship project.

Wheelock in aCult House Walk into a men's cult house in New Guinea (sorry, ladies, they really are for men only) and you confiont a host of ancestor boards—gope boards-propped against the walls. Highly stylized but carefully individualized, each board represents a separate clan ancestor. People set food and valuables in front of the boards as offerings to the powerful ancestral Spirits. "It's an attempt of the living to control the world around thern," says visiting professor of anthropology Robert Welsch. "It's also a way of extending memory way back. Americans choose other ways to leave their offerings, but they too have their ancestor houses. For many years the third floor oi Wilson Hall was lined with portraits of Dartmouth's presidents and famous alumni, including the classic paintings of Eteazar Wheelock and Daniel Webster. "This was Dartmouth's ancestor house," maintains Hood Museum director Timothy Rub.

Writer REBECCA BAILEY plays artfully on the floor in South Strafford, Vermont.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

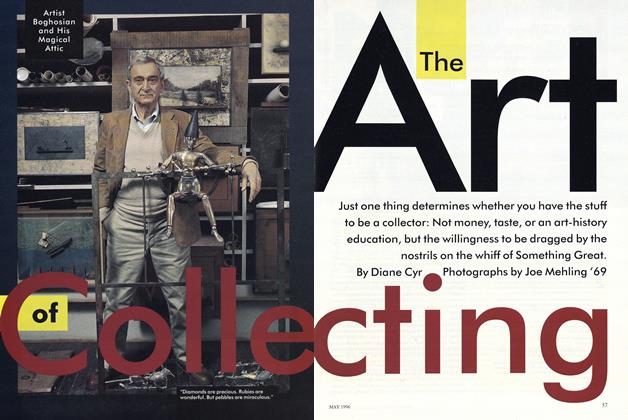

FeatureThe Art of Collecting

May 1996 By Diane Cyr -

Feature

FeatureA Mini-Seminar On Two Hood Pieces

May 1996 -

Feature

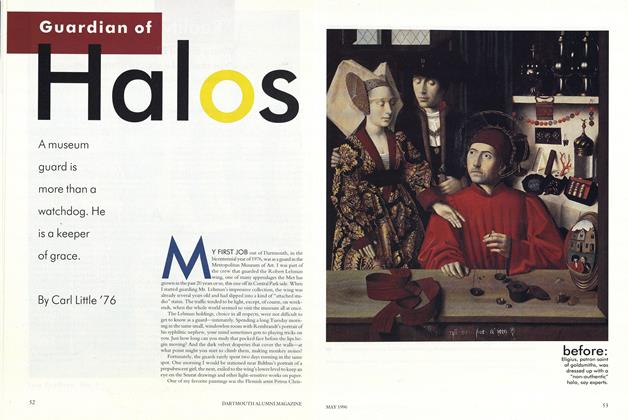

FeatureGuardian of Halos

May 1996 By Carl Little '76 -

Feature

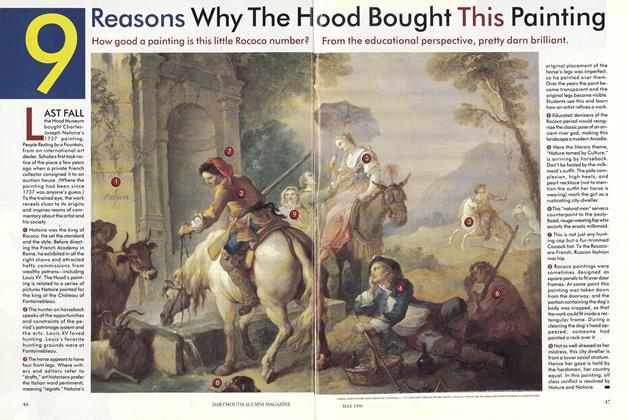

Feature9 Reasons Why the Hood Bought This Painting

May 1996 -

Article

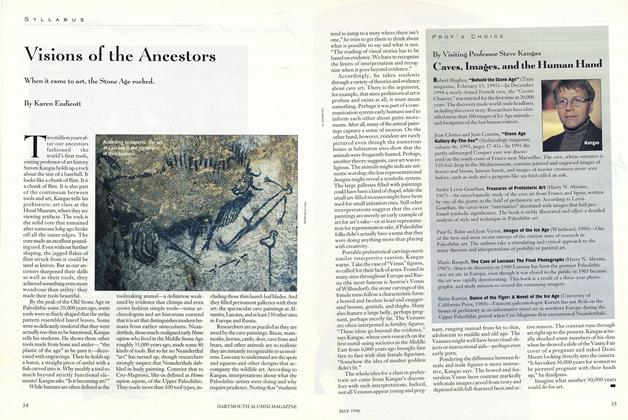

ArticleVisions of the Ancestors

May 1996 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleBaseball Weather Brings Bulldozers

May 1996 By "E. Wheelock"

Rebecca Bailey

Features

-

Feature

FeatureArt Collector and Author

APRIL 1968 -

Feature

FeatureSecond Panel Discussion

October 1951 By ARTHUR L. GOODHART -

Feature

FeatureThe Impact of Defense on the Economy

May 1961 By GEORGE E. LENT, PROFESSOR -

Feature

Feature"Love in a Cold Climate" and Other Cures for the Winter Blahs

JANUARY/FEBRUARY • 1987 By Lee Michaelides -

Feature

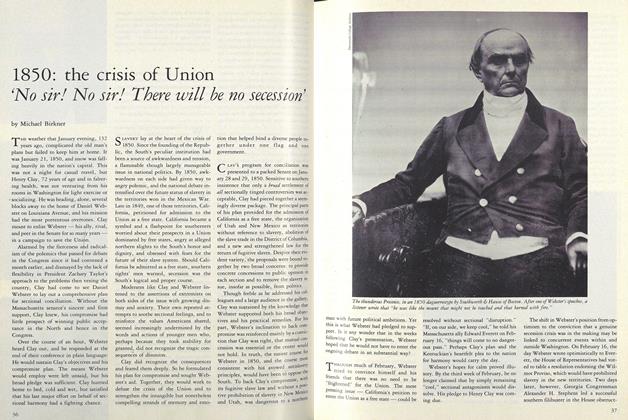

Feature1850: the crisis of Union 'No sir! No sir! There will be no secession'

MARCH 1982 By Michael Birkner -

Feature

Feature'A need for someone who holds my views'

November 1979 By William M. Hill