When it came to art, the Stone Age rocked.

Two million years after our ancestors fashioned the world's first tools, visiting professor of art history Steven Kangas holds up a rock about the size of a baseball. It looks like a chunk of flint. It is a chunk of flint. It is also part of the continuum between tools and art, Kangas tells his prehistoric-art class at the Hood Museum, where they are viewing artifacts. The rock is the solid core that remained after someone long ago broke off all the outer edges. The core made an excellent pounding tool. Even without farther shaping, the jagged flakes of flint struck from it could be used as knives. But as our ancestors sharpened their skills as well as their tools, they achieved something even more wondrous than utility: they made their tools beautiful.

By the peak of the Old Stone Age or Paleolithic some 20,000 years ago, some tools were so finely shaped that the strike pattern resembled laurel leaves. Some were so delicately rendered that they were actually too thin to be functional, Kangas tells his students. He shows them other tools made from bone and antler— "the plastic of the age" as he puts it—decorated with engravings. Then he holds up a baton, a straight piece of antler with a fish carved into it. Why modify a tool souch beyond strictly functional elements? Kangas asks. "Is it becoming art?"

While humans are often defined as the toolmaking animal—a definition weakened by evidence that chimps and even crows fashion simple tools—some archaeologists and art historians contend that it is art that distinguishes modern humans from earlier antece dants. Neanderthals, those much-maligned early Homosapiens who lived in the Middle Stone Age roughly 35,000 years ago, made some 80 kinds of tools. But so far no Neanderthal "art" has turned up, though researchers strongly suspect that Neanderthals dabbled in body painting. Contrast that to Cro-Magnons, like us defined as Homosapiens sapiens, of the Upper Paleolithic. They made more than 100 tool types, including those thin laurel-leaf blades. And they filled permanent galleries with their art: the spectacular cave paintings at Altamira, Lascaux, and at least 230 other sites in Europe and Russia.

Researchers are as puzzled as they are awed by the cave paintings. Bison, mammoths, horses, cattle, deer, cave lions and bears, and other animals are so realistic they are instantly recognizable to us moderns. Less easy to understand are the spots and squares and other designs that accompany the wildlife art. According to Kangas, interpretations about what the Paleolithic artists were doing and why require prudence. Noting that "students tend to jump to a story where there isn't one," he tries to get them to think about what is possible to say and what is not. "The reading of visual stories has to be based on evidence. We have to recognize the limits of interpretation and recognize when it goes beyond evidence."

Accordingly, he takes students through a variety of theories and evidence about cave art. There is the argument, for example, that since prehistorical art is profuse and exists at all, it must mean something. Perhaps it was part of a communication system early humans used to inform each other about game movements. After all, many of the animal paintings capture a sense of motion. On the other hand, however, reindeer are rarely pictured even though the numerous bones at habitation sites show that the animals were frequendy hunted. Perhaps, another theory suggests, cave art was religious. The animals might indicate animistic worship; the less representational designs might reveal a symbolic system. The large galleries filled with paintings could have been a kind of chapel, while the small art-filled recesses might have been used for small initiation rites. Still other interpretations suggest that the cave paintings are merely an early example of art for art's sake—or at least representation for representation sake, if Paleolithic folks didn't actually have a sense that they were doing anything more than playing with creativity.

Portable prehistorical carvings merit similar interpretive caution, Kangas warns. Take the case of "Venus" figures, so called for their lack of arms. Found in many sites throughout Europe and Russia (the most famous is Austria's Venus of Willendorf), the stone carvings of the female torso follow a characteristic form: a bowed and faceless head and exaggerated breasts, genitals, and thighs. Many also feature a large belly, perhaps pregnant, perhaps merely fat. The Venuses are often interpreted as fertility figures. "These ideas go beyond the evidence, says Kangas, whose own research on the first metal-using societies in the Middle East from 6,000 years ago brought him face to face with slim female figurines. "Somehow the idea of mother goddess didn't fit."

The whole idea for a class in prehistoric art came from Kangas s discomfort with such interpretations. Indeed, not all Venuses appear young and pregnant, ranging instead from fat to thin, adolescent to middle and old age. The Venuses might well have been ritual objects or instructional aids—perhaps even early porn.

Pondering the difference between female and male figures is more instructive, Kangas says. The bowed and featureless Venus faces contrast markedly with male images carved from ivory and depicted with full-featured faces and cative stances. The contrast runs through art right up to the present. Kangas actually shocked some members of his class when he showed a slide of the Vanity Fair cover of a pregnant and naked Demi Moore looking directly into the camera. "It has taken 30,000 years for women to be pictured pregnant with their heads up," he deadpans.

Imagine what another 30,000 years could do for art.

According to experts, the art at Lascaux is the signature of true humans.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

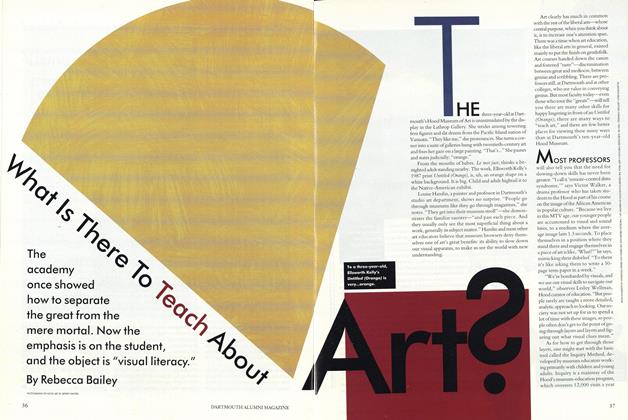

Cover StoryWha is There to Teach About Art?

May 1996 By Rebecca Bailey -

Feature

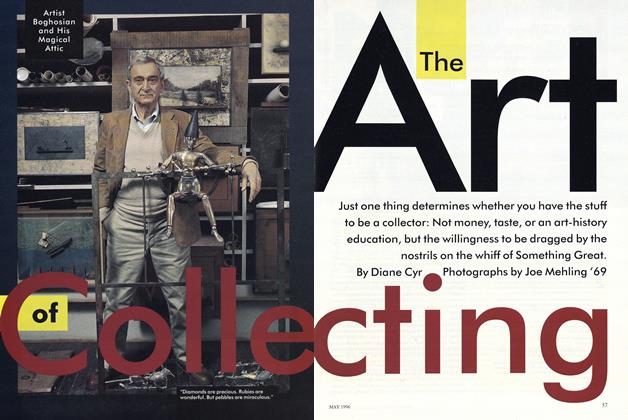

FeatureThe Art of Collecting

May 1996 By Diane Cyr -

Feature

FeatureA Mini-Seminar On Two Hood Pieces

May 1996 -

Feature

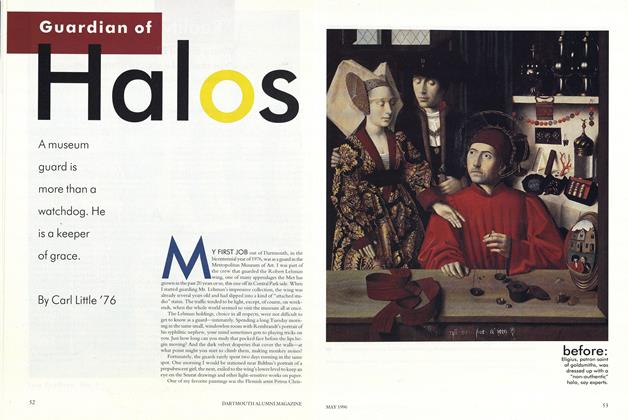

FeatureGuardian of Halos

May 1996 By Carl Little '76 -

Feature

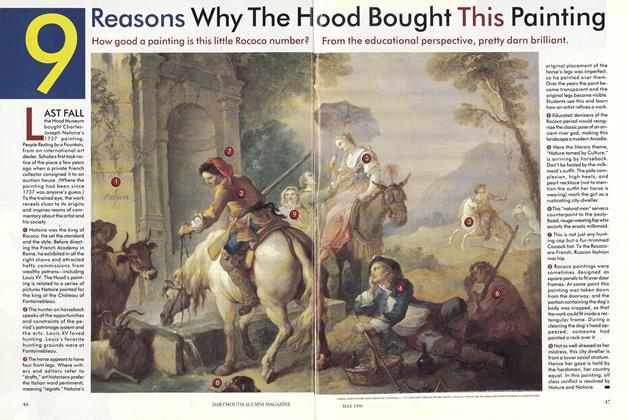

Feature9 Reasons Why the Hood Bought This Painting

May 1996 -

Article

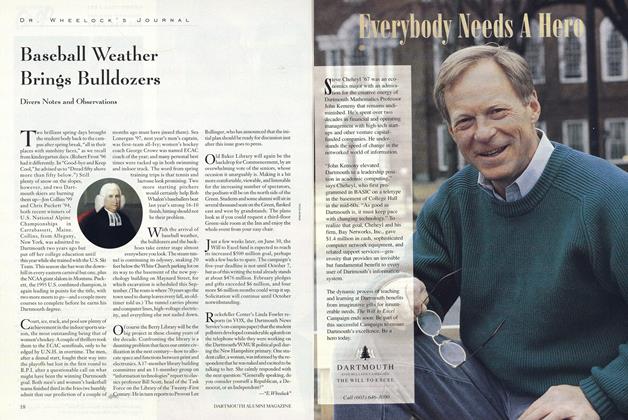

ArticleBaseball Weather Brings Bulldozers

May 1996 By "E. Wheelock"

Karen Endicott

-

Feature

FeatureRooming with Style

NOVEMBER • 1987 By Karen Endicott -

Cover Story

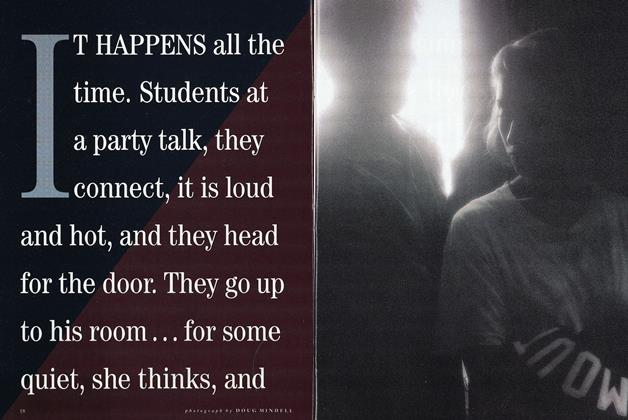

Cover StoryThen lings get ugly

NOVEMBER 1992 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleSlesnick by the Numbers

SEPTEMBER 1994 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleThe World's a Game

April 1995 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleWHAT the ELDERS WROTE

October 1995 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleJapan's Ambivalent Story

OCTOBER 1988 By Mary Scott, Karen Endicott