Women have not just added new courses tothe curriculum. They have helped changethe way material is taught.

be making the young man so uncomfortable, she pointed out, was that a woman was speaking so frankly at Dartmouth.

Twenty-five years into coeducation, women and their perspectives are no longer a novelty on either side of the lectern. Women compose about half of the student population, 29.5 percent of all faculty, and 27.4 percent of tenured faculty the highest proportion of female teachers in the Ivy League. But the changes women have wrought are more profound than the numbers. Courses on gender and feminist theory introduced to the College by women, for the most part now run throughout the curriculum, influencing scholarship well beyond the Women's Studies Program. And the very way that courses are taught has changed as well.

At the dawning of coeducation, however, the College focused on what Dartmouth could do for women's minds, not what women's minds would do for Dartmouth. Dean of Faculty James Wright recalls the coeducation discussions that took place almost as soon as he arrived in 1969: "I think a part of it was a recognition that if schools like Dartmouth were going to do what we thought of ourselves as doing, which was to educate and empower young people to assume positions of responsibility in our society, then we had a responsibility to educate and empower more than just men," says Wright. "I don't think anyone could have predicted just how significantly women would enrich the intellectual life here. It was seen as a matter of fairness."

Early on, in fact, the College made no pretensions of what women wanted in the first place. Welcoming the first coeducational class at the 1972 Convocation, President John Kemeny cautioned Dartmouth against presupposing women's needs. "It remains to be seen whether the academic interests of Dartmouth women might not be closer to those of Dartmouth men than, let's say, those of Harvard men," Kemeny told the assembled students. He bluntly told the faculty not to advise women students to enter "the feminine professions."

Women certainly were not entering a feminine place. After 200 years of single-sex education, faculty and students employed a "certain kind of masculine connivance," says classics professor Edward Bradley, who came to Dartmouth in 1963. "Men alone young men and a male teacher could avail themselves in the classroom of a larger shared sense of their maleness, such as to get the class's attention by referring to something that touched slightly on the erotic. This opportunity for men to slouch intellectually was simply taken away from them when women came."

Women who came to teach faced another side of Dartmouth masculinity. Forty of the 281 faculty were women in 1973. When they came up for tenure, they were rejected at a higher rate than their male peers. Student evaluations were the main reason, says Marianne Hirsch, professor of French and Italian and of women's studies. The women lecturers failed to "fit the image of the guy in a tweed suit, with a loud voice and a pipe," she says. History professor Mary Kelley, who now routinely turns up on lists of best teachers, recalls a male student who came to class when she started teaching in 1977 and said, "Oh, you're a woman, I'm not taking your class." Says Kelley, "I thought it was a joke. I'm sure he didn't."

A practical solution arose when speech lecturer Merelyn Reeve volunteered to teach junior faculty women how to develop their skills as public speakers. "It wasn't a question of trying to imitate the ideal male teaching style," says Hirsch, one of Reeve's early faculty students. "It was a question of finding your own style." Reeve's classes were so successful that men soon asked to join them.

Two decades later, both men and women professors embody a range of teaching styles, from brash theatricality to formal erudition to the Socratic method. "There's an expanded sense of what makes a good professornot simply the model of an avuncular male lecturer, " says Dean Wright. Observes English professor Don Pease, "Women are often better in smaller classrooms, getting students to discuss a book on an intimate level, in a way that many men would be unable to do."

Some professors adopt styles that reach out particularly to women. History professor Annelise Orleck's approach comes out of the women's movement's emphasis on breaking down "social hierarchies." She incorporates discussion into every class. When she does lecture, she uses what she calls a "permeable" style in which she encourages questions. "When you do this, you take certain risks because you can't guarantee you will get across all you want to," Orleck admits. "But, then, studies show that students remember most when they participate the most. They remember what they say, not what you say."

Physics professor Delo Mook has tried to use a more female-friendly teaching style to get through to women students, who tend to drop out of sciences more readily

than men. Mook recalls seeing a woman who had just flunked one of his exams comparing notes with a male student. "It turned out he had done just as badly as she had. Her attitude was, 'Should I go on with engineering?' His attitude was, 'Ah, the profs an asshole,' and he dropped the exam in the trash basket. Classic example of the difference in gender upbringing. He didn't succeed, so it's someone else's fault. She didn't succeed, so she internalized it."

Citing the book Women''s Ways of Knowing, which he coteaches in a women's studies class with English senior lecturer Priscilla Sears, Mook says that women often make emotional connections to what they are studying. So he tries to put more warmth and emotion into his physics teaching. He asks students to say what they feel about his lecture, and he shows joy when someone who has been struggling starts to get a foothold. Perhaps most importantly, he rewards such success by asking women students who have devised new ways of understanding class material to place their explanations on a computer file for other students. While Mook's emphasis is on teaching women better, he says that men also benefit. "I've had people call from the Thayer School and say, 'My God, what are you doing? I've never had students do so well in field theory before.'"

In government classes, a traditional bastion of go-for-the-throat debate, women senior thesis students began a practice in the early 1990s of meeting for snacks and commiseration. The next year government professor Lynn Mather convinced the department to sponsor regular, informal gatherings for all its honors thesis students, male and female, and a tradition began. The get-togethers allow the seniors to "gripe about how hard it is, and once people realize it's hard for everyone, they can get up and move on," said Mather. "We keep the harderedge thinking, but what's wrong with holding hands? We all need our hands held!"

Indeed, encouragement has always been at the base of traditional Dartmouth mentorship. Before coeducation, professor-student interaction was less formal and more social. Professors would put up students' dates on big weekends and invite choice students over for cross-country skiing and home-cooked meals. That system no longer exists, if for no other reason than the high cost of housing near campus, which has driven faculty to outlying areas. Instead, the College has encouraged more formal forms of mentorship such as the Presidential Scholars program, which links students and professors in research projects.

In 1990 chemistry professor Karen Wetterhahn and then assistant dean of engineering Carol Muller 77 founded the Women in Science Project, a mentoring program tailored to encourage women to major in science, math, and engineeringfields traditionally dominated by men. WISP offers research internships, runs seminars for men and women, and provides students with e-mail links to scientists nationwide. Since WISP began, the proportion of female science majors at Dartmouth has increased from 15 to 24 percent; in 1996, women majors outnumbered men in biology and earth sciences.

Although most of its programming is open to all students, WISP reserves its first-year internships for women. Engineering professor Ursula Gibson '76 questions the wisdom of providing different science experiences for men and women. "I teach a technology class, and I can divide students up in terms of their initial performance better by their extracurricular activities than by gender," she says. "Those who take part in more active, aggressive activities are more willing to jump in and take risks." She suggests that programs like WISP might be based more appropriately on a measure of students' selfconfidence rather than on gender.

"Self-confidence is only one issue women face in science," counters Wetterhahn. "There are other issues as well, such as lack of hands-on experience." She maintains that science is the real winner. "I think the more people you have in science, the more ideas you have, and the more ideas you have, the quicker you move forward. I don't see it as a gender issue, I see it as having different people involved, a better mix."

Where women's intellectual impact has been greatest and, for some, most controversial, is in the actual content taught in the classroom. "Much of the expansion of knowledge in the past 25 years, especially in the social sciences and humanities, has taken place because of the nature of inquiries women have brought to many disciplines," says Dean Wright, a historian. At Dartmouth, "virtually every department has courses that have resulted from some of this new inquiry," he adds.

Indeed, the College offers some 70 courses that cover gender issues or feminist analysis. Faculty research on gender has covered subjects ranging from the place of early modern women in the development of a concept of French national identity to free speech and rights conflicts to the "virgin" metaphor used by Spanish conquistadors. Students are doing gender-focused research on their own. Recent senior theses and projects have looked at women and fairy tales in seventeenth-century France, the role of women's organizations in supporting women who run for Congress, and Vietnamese female Francophone writers.

This intellectual upwelling happened fairly recently in College history. Twenty-five years ago, academic feminism and its progeny, gender studies, were barely on the national horizon, let alone the Hanover Plain. Syllabi contained so few works by women that Blanche Gelfant even raised eyebrows when she taught Willa Cather. In 1978 women faculty, led by historian Marysa Navarro and English professor Brenda Silver, created the Women's Studies Program. Participating faculty challenged one canon after another, pushing departments to develop new courses and re-examine traditional reading lists. "Why should reading Virginia Woolf cause someone to have a conniption fit that we might not read James Joyce?" asks German professor Ulrike Rainer. "To me, of course, you can read both. Why not?" Historian Mary Kelley says that in the early years of the program, "I would get on my student evaluations comments along the line of, 'She's a wonderful teacher despite the fact that she's a feminist.' I couldn't understand why this was feminist, to simply include half the population."

Kelley attracted many takers when, as John Sloan Dickey Third Century Professor of the Social Sciences from 1991 through 1996, she offered modest grants to help faculty add the study of women and gender to existing courses or design new courses drawing on those topics. The funds supported such topics as Latin American women's history and women and men in medieval and Renaissance Europe. A grant also helped geography professor Adrian Bailey add recent feminist scholarship in a course called "Population Geography." Government professor Nelson Kasfir used the funds to consult with experts on African women. His colleague Thomas Nichols added consideration of gender issues to a course on Soviet and post-Soviet politics. History professor Judith By field '80 developed a new course on women and the state in Africa.

Women's studies, now 18 years old, reports healthy enrollments (last fall's intro course had 96 women and 23 men) a marked difference from the late seventies and early eighties, when class sizes were so small that the College easily could have pulled the plug on the program. What is more, the study of women and gender issues has spread beyond the program's courses. For example, the social sciences and sciences now recognize the fallacy of generalizing about whole populations while studying only male subjects or using gender-biased datagathering methods. "It's no longer a political issue to be a woman here and to teach women's products in many fields," says associate dean Mary Jean Green. "You don't have to be a political activist."

John Collier'72, Th'77, a Thayer School professor, recalls an incident from his undergraduate years when a friend came to him in a panic. The friend was about to go on his first date with a woman. "He asked me, quite seriously, 'What do you talk about with a girl?' He hadn't the slightest clue."

A male student in the nineties is likely to discuss ideas with a woman. "Now," says Collier, "there's a continuity and interaction and ability to build friendships, to learn that women have different perspectives that are very useful to know about."

Sometimes the idea of male-female perspectives goes too far, however, says Collier's engineering colleague Ursula Gibson. She maintains that the divide between men and women is wider than ever. Women students seem "very tuned into male-female tensions and gender awareness," Gibson says. "When I was here, I felt like an individual, I judged others as individuals, and for the most part I think I was judged that way. It's almost as if the pendulum has gone past the ideal point."

But English professor Don Pease argues that "distinctions of gender, class, ethnicity, and other traits will not and should not fade with time, no matter how strong one's desire for unification. These are not unifiable fault lines and never should be," he says. "It is unethical for those fault lines to disappear. If they do, so does the awareness of the difference."

A quarter century after the arrival of women, Dartmouth may still be straggling to find the right balance. But in one sense the College has come of age. These are the straggles of a decidedly coeducational institution.

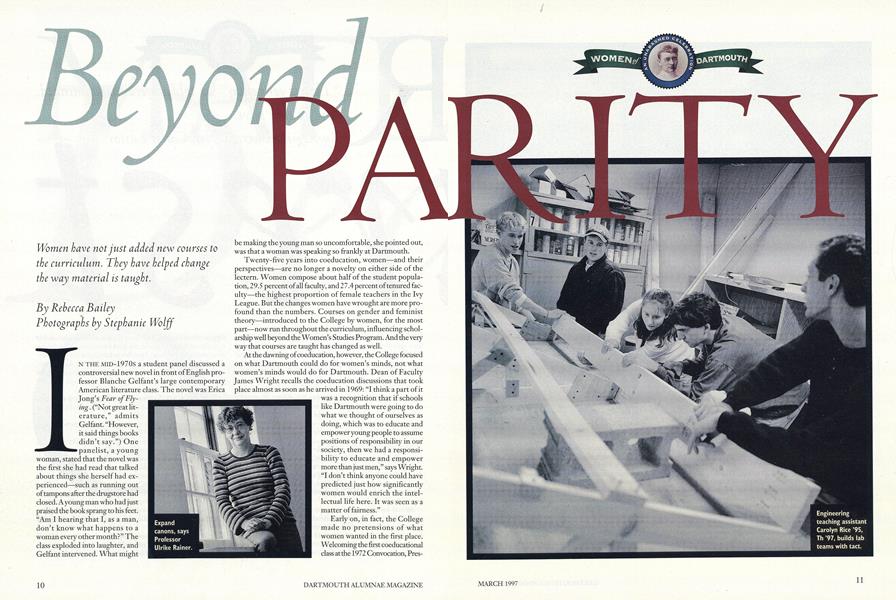

Expandcanons, saysProfessorUlrike Rainer.

Engineering teaching assistant Carolyn Rice '95, Th '97, builds lab teams with tact.

Priscilia Sears andDelo Mook co-teachlinks betweenphysics, literature,and feminism.

Biology majorAna Baptista '98is a rule, notan exception.

Women are no longer a political issue at Dartmouth, says Dean Mary Jean Green.

Jennifer Daniel '97 shows the old College new moves.

Reberca Bailey's last article for this magazine, "A Billion Dollars,"appeared in the November issue.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

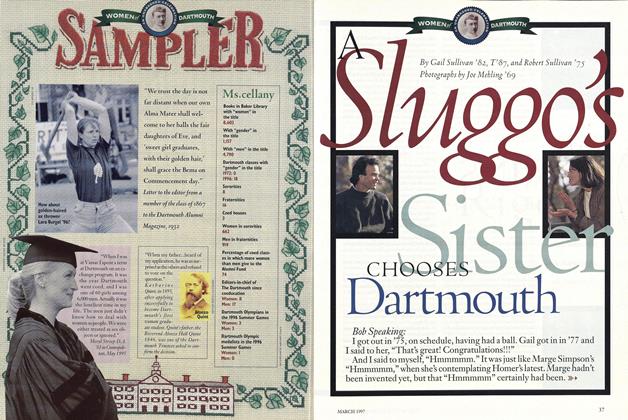

FeatureA Sluggo's Sister Chooses Dartmouth

March 1997 By Gail Sullivan '82, T'87, and Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

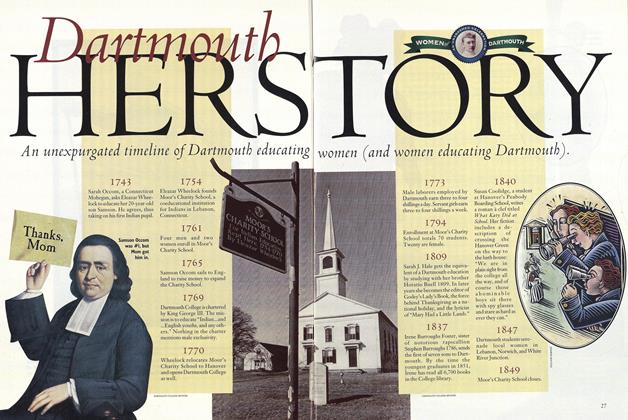

FeatureDartmouth HERSTORY

March 1997 -

Feature

FeatureKnowing Squat About the Woods

March 1997 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Most Influential Women Influential Women

March 1997 By Patricia E. Berry '81 -

Feature

FeatureWhy Dartmouth is Better with Men

March 1997 By Jane Hodges -

Cover Story

Cover StoryMater Dearest

March 1997 By Regina Barreca '79

Rebecca Bailey

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryWha is There to Teach About Art?

MAY 1996 By Rebecca Bailey -

Feature

FeatureA Billion Dollars

NOVEMBER 1996 By Rebecca Bailey -

Article

ArticleFace To Watch

MAY 1997 By Rebecca Bailey -

Article

ArticleA Small Volume, Yet...

JUNE 1997 By Rebecca Bailey -

Feature

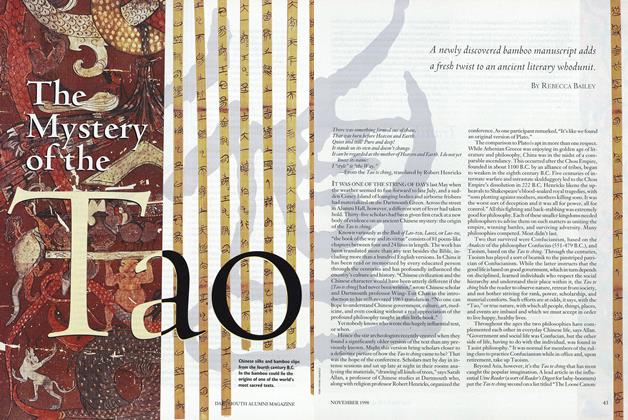

FeatureThe Mystery of the Tao

NOVEMBER 1998 By Rebecca Bailey

Features

-

Feature

FeatureOne Answer for India

APRIL 1971 -

Feature

FeatureANGLOPHILIA HITS THE CAMPUS

MAY 1966 By ARTHUR N. HAUPT '67 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe President Makes His Case

FEBRUARY • 1988 By James O. Freedman -

Feature

FeatureThe Road Not Taken

April 1977 By JOHN S. MAJOR -

Feature

Feature1850: the crisis of Union 'No sir! No sir! There will be no secession'

MARCH 1982 By Michael Birkner -

Feature

FeatureBACK TO THE BOOKS

FEBRUARY 1964 By R.J.B.