A Sluggo's Sister Chooses Dartmouth

MARCH 1997 Gail Sullivan '82, T'87, and Robert Sullivan '75Bob Speaking:

I got out in '75, on schedule, having had a ball. Gail got in in '77 and I said to her, "That's great! Congratulations!!!"

Ours mine and Gail's and our brother Kevin's was one of those first generation to go away to college families, and so we knew nothing of other schools. But I, at least, knew about Dartmouth—big time. And I knew about women at Dartmouth. Or so I thought. Or so I feared.

coeducation and year-round operation, and other things that we, at 18 and 19 and 20, would actually get to vote on. Mine had been the transitional class the forgotten, unequivocally non-historic class. Admitted all-male, we spent freshman year with one another guys, and with the termtransfer gals from the Seven Sisters, whom we liked for liking Dartmouth. We also spent the year, 1971-72, in intense political debate. There was Cambodia, of course, and Vietnam and all that, and then there was CYRO

Remember those referenda, fellow oldtimers? Ha! Like the Trustees were going to listen to us! We voted at the Hop, didn't we? Wherever. Who won? Does anyone remember? Didn't C win and YRO lose? That's the way I recall it. Doesn't matter. Talk about vox clamantis en deserto! Deserto a la mode. Women were in, year-round operation was in, and we were told: "Deal with it, bubba!"

I see that the implication of the prior paragraph paints me a Neanderthal. In truth, I fell short of that noble designation, though if you had accused me of falling short back then I would've put up my dukes. But there is evidence: A year after the CYRO vote, there was another ballot. Heorot was deciding on whether or not we should sink coeds (for those who don't know Greek: That last phrase is vigorously feminist). I was in the beleaguered superminority, but, yes, I voted GIRL. (Remember that meeting, Jon Low? Remember, Dave Bracken? Was there anyone else?) That's why I always liked Heorot. I mean, as opposed to, say, Humpty Dump or the Nu. Can you non-Heorotians believe that Heorot Heorot! ever for a second considered sisters? Well, we did. We had imagination.

But let's not get off on a Heorot jag, for goodness sake. The point is, I had a sister, the aforementioned Gail, and she was and is a sister that I thought (and still think) very well of.

Gail was the brains in the family. (Like that's hard to believe!) And so, sure, of course she would want Dartmouth, and Dartmouth her. But Harvard wanted her too. Why, then, this unreasonable early-decision decision for Big Greenerhood?

Let's ask her.

Gail Speaking: Well, it was your fault. Youknow that. Don't put it on me, like it was somefailing.

I'll explain to the others... .My introduction to Dartmouth came in 1971 when my brother started his freshman year. I immediately wanted to go there too, mainly because, at 11 years old, I still wanted to copy almost everything my brothers were doing, and because I had come to the conclusion, having visited Bobby, that Dartmouth had to be the most beautiful college in the country.

Now back in 1971, I realized there were obstacles. Primarily, Dartmouth wasn't accepting women. But that didn't change my mind about wanting to attend. Nor did anything else I learned about the place during the seven years between my brother's matriculation and my own.

After the women-eligible question had been wisely rectified by the powers-thatwere in Hanover, I watched closely to see if this, indeed, was the place for me. I heard about "all nighters," and came to know that the finals schedules were, at best, painful. I watched as Bobby....

Bob Speaking: Stop calling me Bobby!

Gail Speaking: Everyone in the family callsyou Bobby.

Bob Speaking: But no one else does. Everybodyat Dartmouth called me Sully.

Gail Speaking: Well people at Dartmouth calledme Sully too, so that wouldn't really make sense inthis piece, to have two Sullys going back andforth.

Bob Speaking: But even you call me Sully!

Gail Speaking: And you call me Sully!

Bob Speaking: That's my point!!

Gail Speaking: You can't be Sully and I can'tbe Sully. Wouldn't work. I'll try to call you Bob.

Bob Speaking: Do, or I'll start callingyou GayGay. Remember Gay-Gay?

Gail Speaking: All right, BOB. Now let mecontinue....

As I was saying, I knew finals were a bear, and watched as Bob (God we never call you Bob!) as this guy named Bob struggled through Ulysses over Thanksgiving holiday. But I figured tribulations such as these would not, could not be unique to Dartmouth. As to things more exclusively Green, I was introduced, as an observer, to beer pong, and even to Heorot's Medieval Banquet....

Bob Speaking: You came to a Banquet!?!?!?

Gail Speaking: I saw your pictures.

Bob Speaking: I showed you pictures?!?!?!?

Gail Speaking: You seemed proud of them.

Bob Speaking: Geeeez, Louise!

Gail Speaking: Anyway....

I saw all this stuff at a not-too distant remove, but still wanted to attend college in Hanover. First of all, I wanted to experience some academic rigor—l really did. And seeing Bob sweat as he did indicated there were rigors to be found in the Upper Valley. And then, the fraternities didn't seem all that bad; the people in them seemed, in fact, very nice. And finally there lingered that beauty thing, that intangible. I had fallen in love with Mt. Moosilauke, the Dartmouth Skiway, and homecoming bonfires.

I'm a little embarrassed to admit that my reasoning for wanting to attend Dartmouth didn't go much deeper than that. I was reflecting on this shallowness recently after I spoke with a high school senior a guy who was trying to decide between Dartmouth and the University of Pennsylvania. He rightly had given a lot of thought as to how the two experiences would differ, how each would impact his career, his life. He asked many good, detailed questions. I compared his well-developed inquiry to my own, bygone decision-making process. I think, in retrospect, that I should have at least considered the fact that I would be attending a school that was in only its seventh year of coeducation and was still 75 percent male. (I think I should have considered this in particular, since the only education I had known in the previous 12 years was at an all-girls school run by nuns.) But I don't remember wondering at all how "the ratio" might impact me, except perhaps in a few positive ways, such as how easy it would be to make the swim team. I mean, how many good swimmers could there possibly be in a class with just 316 women?

Bob Speaking: Okay, Sull GAIL TransitionTime. A couple brief words here about theyears intervening.

As I said, I got out in' 75, Gail got in in '77 and would arrive on campus in the fall of'78. It seems to me, the Dartmouth that we saw during our cumulative decade wandering the Hanover Plain was a community in vigorous, forced evolution. It was trying to travel from its Neanderthal period to its Modern Man period Modern Man and Woman period with nothing in between, no Rhodesian Man, no Solo Man, no Steinheim Man, no Swanscombe Man, no Cro-Magnon Man. Dartmouth wanted to time-travel epochs in a trimester. Impossible? Dartmouth thought not. And Dartmouth was, I think in retrospect, right to go about the evolution of its singular species this way.

It created some tension when I was there, and some stupidity. I remember the hazing of women. I recall resentment at what they were doing to the bell curve. I even believe, looking back, that there was pressure on them to be "Dartmouth men." One Saturday afternoon I played in a game of mixed, full-tackle rugby, during which a small woman got her back broken; read into that whatever you will. A lot of us in the original class of '75 drank too much, so we thought a cool woman was one who drank too much too. A bunch of guys not Heorotians, not us got blitzed one night and wreaked some pretty serious havoc in the halls of Woodward. Bad stuff. And this was the stuff I was worried about when young Gail started telling Mom and Dad about how she'd like to go to Dartmouth some day too, just like Bobby.

But it seems to me and I aver that this is not colored by the murky gray haze of reminiscence that all of this nonsense changed pretty quickly. Kemeny let it be known that poor behavior was unacceptable, and Dartmouth people are, after all, pretty smart. By the time I graduated, the men and the increasing numbers of women were brothers and sisters, by and large we're all in this together,up here in the woods, clamantising in de unitas.And while we're at it, Let's BeatHarvard! My dorm, Hitchcock, was one of those hyper-liberal room-by-room dorms: Your neighbor was of the other sex, no matter which sex you were. And by junior year I found myself pals with a lot of my neighbors. I remember sitting out on the back roof of Hitchcock on spring evenings, talking things over with Laurie Keeshan '75—we called her Laurie, not The Keeshmonster or Cap'n's Daughter—things that I would never broach with Stumpy or Grit or Melon or Doc Perverto. This was good, I found. Different, but perfectly good.

To best measure the quick progress that was made, consider Kemeny. On campus at least, if not among those big-bucks adults out there who were juicing the nascent Dartmouth Review, he had gone, in three short years, from being a symbol of something bad or at least radical to being perceived, generally, as a visionary. A sage. A Big Green Moses.

By senior year we were, in dorm debates, chiding later-comers to the chosen land. (Amherst stayed all-male too long, I believe, and there were one or two others.) We called them anti-progressive, recalcitrant.

And so by the time Gail prepared for her northward journey, packing her records and books into the Chevy from which my books and records had only recently been unpacked, I was, if still a bit concerned, if still going Hmmmmm a la Marge, I was essentially....

What was I, Gail? Do you remember?

Gail Speaking: You were proud, I rememberthat. Happy for me. Not worried too much, Idon't think. I think you were convinced that itwas a different enough place, that it was safe foryour little sister.

And I found a good, safe place. I found things I expected—the rigor, the aesthetic and things that surprised me, too.

What I found at Dartmouth right off the bat was a bunch of good women swimmers. In fact, there were a lot of talented women in just about every field. Although I'm sure I experienced my share of freshman jitters, they were not female freshman jitters. I never felt outnumbered by men. It seemed that all around there were women leaders: president of the Dartmouth Outing Club, managing editor of The Dartmouth, all the usual resume items that lead to a C&G tap. Perhaps women were succeeding because they were striving that much harder to excel, in the way minorities often do to prove their worth. For me, if that was a motivating factor, it was subconscious. In fact, I remember early on at Dartmouth I took a lot of math and science classes, the kind of intro courses many students took during their freshman year....

Bob, should we reminisce about our respectivecalculus experiences?

Bob Speaking: Oh, absolutely. And then we'llproceed to Shakespeare and Marlowe, Miltonand....

Gail Speaking: Okay, okay. Enough.

In any event, in those freshman classes on those high-stress tests days, I was clearly just another student, another walking ID number, another breathing Hinman box address. It was simply impossible to feel I was suffering any discrimination.

A couple of concessions: Maybe my experiences within an all-women dorm Woodward, Bob! and on a women's sports team colored my perceptions on equality and inequality somewhat. And maybe it was that times had already changed. I have heard reports that it was not as easy for women in earlier classes to fit in, and I don't doubt the reports. But I can only speak for myself, and in 1978 I immediately felt an equal member of my freshman class. Dartmouth did not feel oppressive. I've witnessed much more genderbias in my post-Dartmouth days. I would tend to agree with Bob though it always pains me to agree with Bob that Dartmouth seemed to move pretty fast at changing things, at changing itself, back in the seventies.

Of course, there was room for improvement. I would have liked more women professors. Fraternities were great fun, but also had a dark side. Social alternatives were limited.

Bob Speaking: Not as limited as they had been.Gail Speaking: Really?

Bob Speaking: Yeah, in retrospect I would say so.Basically, we had the frats. Dorm parties and thefrats. The things at the Hop were okay freshmanyear, but they seemed hopelessly old-fashionedlike a mixer out of Fitzgerald or something. Theywere boys' schoolremnants.

So there were those things. And then of course,we road-tripped. That was an alternative, and itwas fun no question. But would we have done itif there had been more choices in Hanover? No.

The road-tripping is an interesting thing to lookat. You see, we formed these frat-guy habits, and thatwas part of the reason for the early tension. It's senioryear, and we're still road-tripping to Colby,because it is our habit and because we have old friendsthere. Well, what did this look like to others on campus to the women, and to some in the underclasses?Insulting and hidebound behavior, that's what itlooked like.

But you guys in the subsequent classes honedother instincts entirely. You built on amended traditions.

Remember that Winter Carnival when I visitedyou?

Gail Speaking: Yeah.

Bob Speaking: Entirely different. Entirely differentfrom ours. Ours were somehow more...desperate.Yours were more airy. Yours were brighter.We ate in Thayer or took our dates out for a bigmeal at the Bull's Eye. That spaghetti-fest you guyshad—it was a healthier thing, a vibrant communalscene. Yours was a friendlier Carnival, I thought.Ours were almost entirely nocturnal. I never wouldhave entered that Carnival cross-country ski racethat you and I entered that year. No way, no how.

Gail Speaking: But we were still playing beerpong.

Bob Speaking: Well, that's what evolution'sabout. You retain your most advanced traits. Youhold on to your classics. Beer pong just may be theopposable thumb of a Dartmouth education.

Gail Speaking: How did you feel, visiting ourCarnival?

Bob Speaking: Elated, frankly. Confident foryou, confident for the College.

And as one who had been followed there....Offthe hook. Off the hook with you. Off the hook withthe Vents.

Gail Speaking: Do you think the place has continued to change?

Bob Speaking: Yeah, from what I've seen . I mean,the people still seem larger than people at other colleges,and healthier. Not that there's ever been aDartmouth type exactly, but...we always used to resistthat notion, even in the pre-intellectual-lonerera... but there's something intrinsic that the most blatant and forceful alterations of ethos and student-bodycomposition can't seem to chip away at.

Gail Speaking: Which is good, I think. You canchange greatly, and greatly remain the same. Aninstitution that can do that is a pretty soulful institution.

It's strange...! know my Dartmouth was fardifferent from yours, and from today's. I mean,yours was all-male at first, and today's is half femalethat's a difference, no doubt about it. But tome, Dartmouth, when I got there, did not seem adifferent Dartmouth than Bobby's....

Bob Speaking: Hey!

Gail Speaking: Than the OLD Dartmouth.Nineteen seventy-one, 1978, today, tomorrowa beautiful college filled with talented people.

Bob Speaking: Nothing more.Gail Speaking: Nothing less.

Gail Sullivan is an executive with the GilletteCompany in Boston. Her brother is a senior editorat Life and the author of Flight of the Reindeer.

Gail wasthe BRAINSin the family. (Like that's hard to believe!) Andso, sure, of courseshe would wantDartmouth, andDartmouth her.

Seeing Bob sweatas he did indicatedthere wrer Rigorsto be found in theUpper Valley.

"Beer PONG just may be the opposable thumb of aDartmoutheducation"

"You can CHANGE Greatly, and greatly remainthe same"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

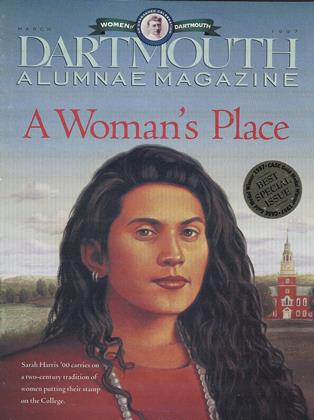

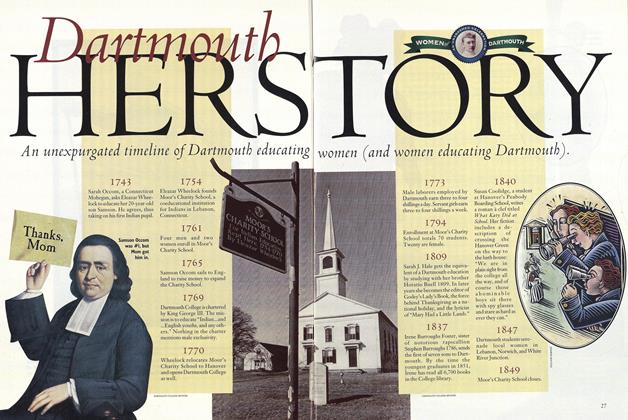

FeatureDartmouth HERSTORY

March 1997 -

Feature

FeatureBeyond PARITY

March 1997 By Rebecca Bailey -

Feature

FeatureKnowing Squat About the Woods

March 1997 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Most Influential Women Influential Women

March 1997 By Patricia E. Berry '81 -

Feature

FeatureWhy Dartmouth is Better with Men

March 1997 By Jane Hodges -

Cover Story

Cover StoryMater Dearest

March 1997 By Regina Barreca '79

Features

-

Feature

FeatureBronx County Chairman

APRIL 1968 -

Cover Story

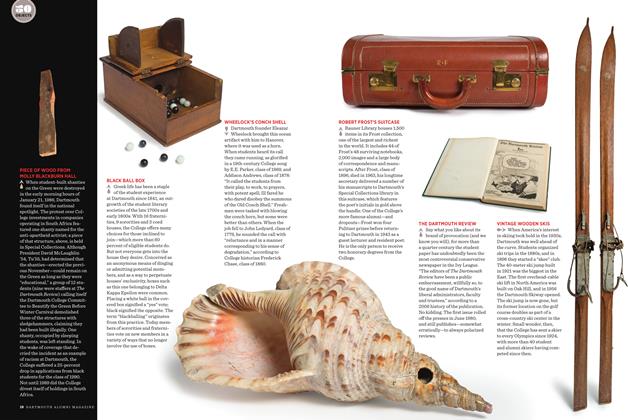

Cover StoryBLACK BALL BOX

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

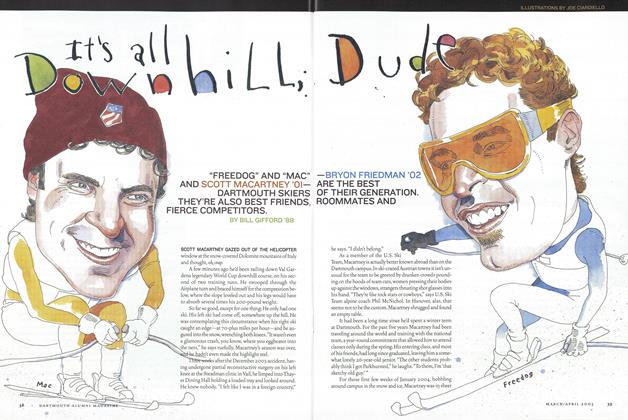

FeatureIt’s All Downhill, Dude

Mar/Apr 2005 By BILL GIFFORD ’88 -

Feature

FeatureTo Screenwriting Born

November 1982 By Budd Schulberg '36 -

Feature

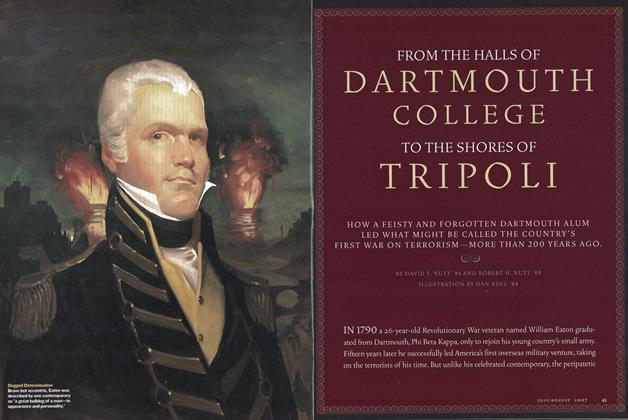

FeatureFrom the Halls of Dartmouth College to the Shores of Tripoli

July/August 2007 By DAVID T. NUTT ’44 AND ROBERT H. NUTT ’49 -

Feature

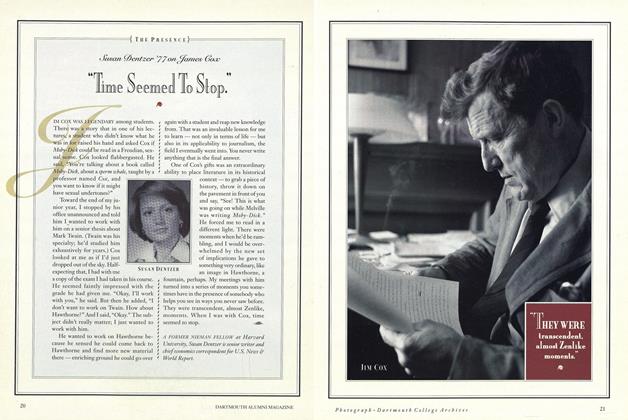

FeatureSusan Dentzer '77 on James Cox

NOVEMBER 1991 By Jim Cox