"Things get better" we told the tradition-minded.And so they have.

ONE OF MY STRONGEST MEMORIES from my first few weeks at Dartmouth is that sinking feeling of being unsure where I was headed. I never knew whether I was in the right classroom, the right building often I felt as though I wasn't even at the right college. (One of my aunts in Brooklyn wasn't so sure either. "You're going to school in New Hampshire?" she asked me. "You're pregnant, right?")

But then came the moment after I had been on campus for awhile, when another poor, dazed, lost soul actually asked me for directions. She thought I knew what I was doing, and when I could answer her questions about the location of the reserve reading room I realized that, in fact, I did know what I was doing. It just didn't feel like it until then.

I get the same feeling reading this issue called the Dartmouth Alumnae Magazine, which brings a distinctively female voice to the cry in the wilderness. The boundaries of "The Dartmouth Experience" are inevitably revised and refigured when they are experienced by newcomers to the northern territories. New people come and give directions.

Still, we need to be reminded now and then that women have actually colonized the joint. The masculine experience tends to be considered universal, which is why women need to get their stories out. Early in the coeducational era, the tales we heard as students about the history and character of the College were ones, necessarily, about men.

This is not a big shock. For a couple of centuries the College had prided itself on making men out of boys. It certainly made a woman out of me. It also made a feminist out of me, which is to say that I subscribe to the radical belief that women are human beings. It was at Dartmouth that I came across one of my favorite passages by the essayist and novelist Virginia Woolf, concerning the way she was barred from entering even the libraries at Oxford and Cambridge, let alone the classrooms. Here was one of the century's greatest authors and she was kept out of the library because the male students and scholars couldn't bear to be disturbed by a woman and they found women essentially disturbing. Woolf wrote how dreadful it is to be locked out. But then it occurred to her that it is "far more dreadful to be locked in."

At mid-seventies Dartmouth I wasn't always sure whether men should be let out. I was introduced to "Dartmouth's in Town Again, Run, Girls, Run" on my freshman trip. We were voted an "eight" as my friends and I walked past Mass Hall on the way to Thayer; collectively, we accepted this as a reasonable, if not generous, score. It didn't occur to us to offer our own signs and numbers as we slid over these established thresholds or to do anything but ignore the guys who shouted out phrases encouraging us (how can I put this politely?) to have their children. This is not necessarily a useful oratorical skill in late twentieth-century America; to the extent that women no longer get public ratings on campus, men have benefited from the change as well.

Before such an enlightened time, I was learning a thing or two myself. "When our fathers were here there were no women," the men used to tell me.

"When your grandfathers were here there were no electric lights," I told them back. "Things get better."

And so they have. In my mind I carry a reminder of this: an image ofus women as we walked to Thayer on an uncharacteristically warm March evening in 1976. Laughing, we seem to be pushing past our predecessors the men in wigs, the boys in tighttrousers, the returning G.I.'s still awkward in their civilianclothes. We "coeds" were not asking to be let in. That was Dartmouth's decision. Having come in through a oncelocked door, wewere helping to show the way out. The students who cameafter us are doing the same thing. This issue tells some of our stories as a collective act of giving directions.

Regina Barreca, a professor of English at the University of Connecticut,is this issue's guest editor. Her latest book is The Erotics of Instruction, due out this spring.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Sluggo's Sister Chooses Dartmouth

March 1997 By Gail Sullivan '82, T'87, and Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

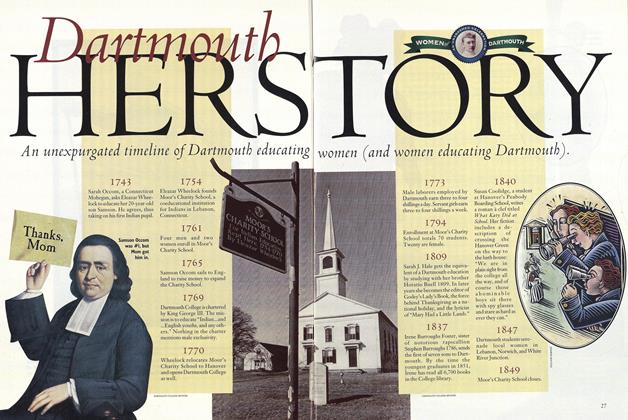

FeatureDartmouth HERSTORY

March 1997 -

Feature

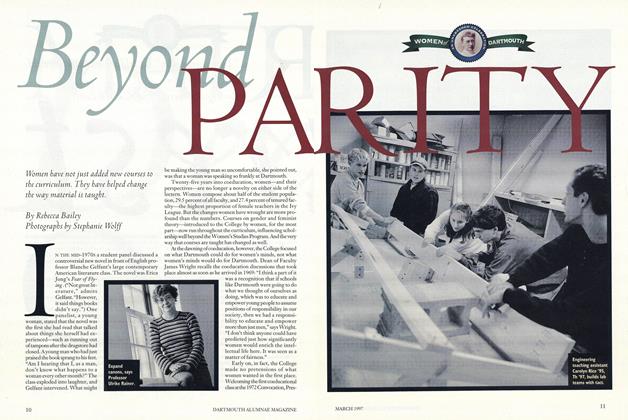

FeatureBeyond PARITY

March 1997 By Rebecca Bailey -

Feature

FeatureKnowing Squat About the Woods

March 1997 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Feature

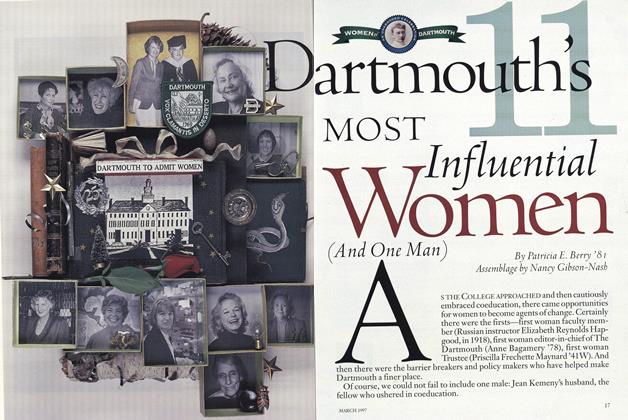

FeatureDartmouth's Most Influential Women Influential Women

March 1997 By Patricia E. Berry '81 -

Feature

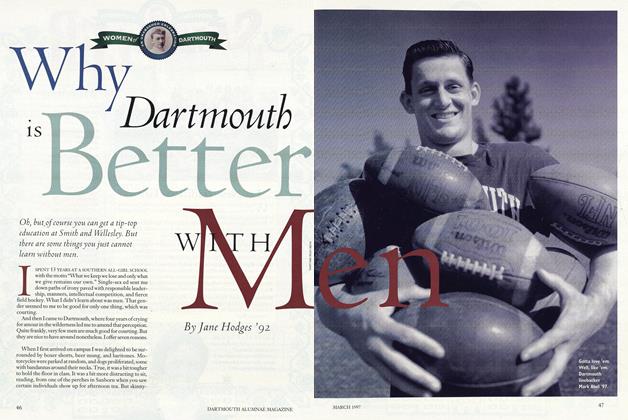

FeatureWhy Dartmouth is Better with Men

March 1997 By Jane Hodges

Regina Barreca '79

-

Feature

FeatureThey Used to Call Me Snow White... But I Drifted

June 1992 By Regina Barreca '79 -

Feature

FeatureThe Next Bus Home

September 1993 By Regina Barreca '79 -

Feature

FeatureTau Iota Tau and Other Brassy Memories

FEBRUARY 1994 By Regina Barreca '79 -

Feature

FeatureAfter Eleven Commencing

June 1995 By Regina Barreca '79 -

Feature

FeatureAfter the FALL

JANUARY 1998 By Regina Barreca '79 -

Feature

FeatureThe Good Sport in Me

March 1998 By Regina Barreca '79

Features

-

Feature

FeatureTrustees Reenact 1770 Board Meeting

DECEMBER 1970 -

Feature

FeatureIt Was A Dartmouth Jinx All the Time

November 1960 By AMOS N. BLANDIN '18 -

Feature

FeatureA Delicate Balance

November 1975 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

FeatureMystery on the Mountain

SEPTEMBER 1987 By Daniel Q. Haney -

Feature

FeatureToday: Views of an Embattled Oilman

April 1974 By WILLIAM K.TELL JR.