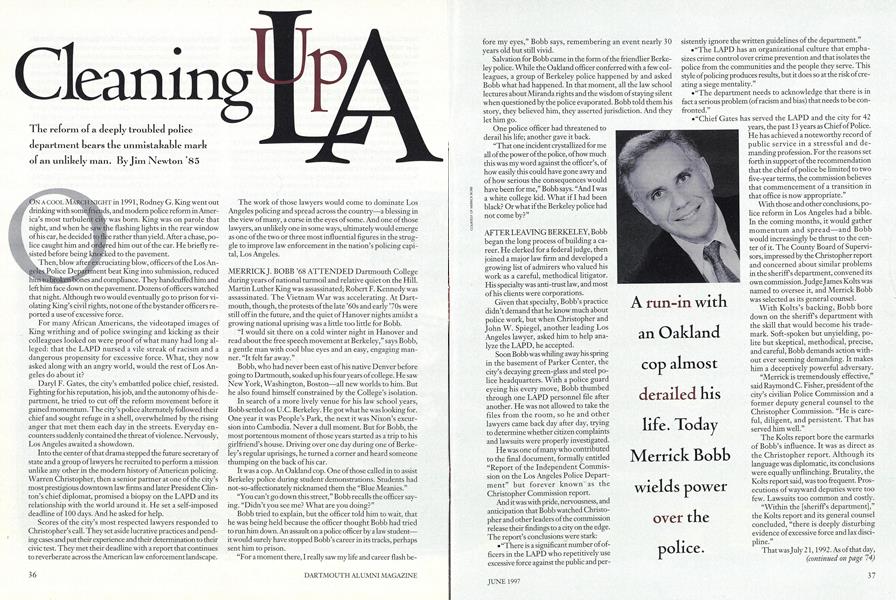

The reform of a deeply troubled police department bears the unmistakable mark of an unlikely man.

ON A COOL MARCH NIGHT in 1991, Rodney G. King went out drinking with some Is, and modern police reform in America's most turbulent city was born. King was on parole that night, and when he saw the flashing lights in the rear window of his car, he decided toffee rather than yield. After a chase, police caught him and ordered him out of the car. He briefly resisted before being knocked to the pavement.

Then, blow afte excruciating blow, officers of the Los Angeles Police Department beat King into submission, reduced him to broken bones and compliance. They handcuffed him and left him face down on the pavement. Dozens of officers watched that night. Although two would eventually go to prison for violating King's civil rights, not one of the bystander officers reported a use of excessive force.

For many African Americans, the videotaped images of King writhing and of police swinging and kicking as their colleagues looked on were proof of what many had long alleged: that the LAPD nursed a vile streak of racism and a dangerous propensity for excessive force. What, they now asked along with an angry world, would the rest of Los Angeles do about it?

Daryl F. Gates, the city's embattled police chief, resisted. Fighting for his reputation, his job, and the autonomy of his department, he tried to cut off the reform movement before it gained momentum. The city's police alternately followed their chief and sought refuge in a shell, overwhelmed by the rising anger that met them each day in the streets. Everyday encounters suddenly contained the threat of violence. Nervously, Los Angeles awaited a showdown.

Into the center of that drama stepped the future secretary of state and a group of lawyers he recruited to perform a mission unlike any other in the modern history of American policing. Warren Christopher, then a senior partner at one of the city's most prestigious downtown law firms and later President Clinton's chief diplomat, promised a biopsy on the LAPD and its relationship with the world around it. He set a self-imposed deadline of 100 days. And he asked for help.

Scores of the city's most respected lawyers responded to Christopher's call. They set aside lucrative practices and pending cases and put their experience and dieir determination to their civic test. They met their deadline with a report that continues to reverberate across the American law enforcement landscape.

The work of those lawyers would come to dominate Los Angeles policing and spread across the country a blessing in the view of many, a curse in the eyes of some. And one of those lawyers, an unlikely one in some ways, ultimately would emerge as one of the two or three most influential figures in the straggle to improve law enforcement in the nation's policing capital, Los Angeles.

MERRICK J. BOBB '68 ATTENDED Dartmouth College during years of national turmoil and relative quiet on the Hill. Martin Luther King was assassinated; Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated. The Vietnam War was accelerating. At Dartmouth, though, the protests of the late '6os and early '70s were still off in the future, and the quiet of Hanover nights amidst a growing national uprising was a little too little for Bobb.

"I would sit there on a cold winter night in Hanover and read about the free speech movement at Berkeley," says Bobb, a gentle man with cool blue eyes and an easy, engaging manner. "It felt far away."

Bobb, who had never been east of his native Denver before going to Dartmouth, soaked up his four years of college. He saw New York, Washington, Boston all new worlds to him. But he also found himself constrained by the College's isolation.

In search of a more lively venue for his law school years, Bobb settled on U.C. Berkeley. He got what he was looking for. One year it was People's Park, the next it was Nixon's excursion into Cambodia. Never a dull moment. But for Bobb, the most portentous moment of those years started as a trip to his girlfriend's house. Driving over one day during one of Berkeley's regular uprisings, he turned a corner and heard someone thumping on the back of his car.

It was a cop. An Oakland cop. One of those called in to assist Berkeley police during student demonstrations. Students had not-so-affectionately nicknamed them the "Blue Meanies."

"You can't go down this street," Bobb recalls the officer saying. "Didn't you see me? What are you doing?"

Bobb tried to explain, but the officer told him to wait, that he was being held because the officer thought Bobb had tried to run him down. An assault on a police officer by a law student it would surely have stopped Bobb's career in its tracks, perhaps sent him to prison.

"For a moment there, I really saw my life and career flash be fore my eyes," Bobb says, remembering an event nearly 30 years old but still vivid.

Salvation for Bobb came in the form of the friendlier Berkeley police. While the Oakland officer conferred with a few colleagues, a group of Berkeley police happened by and asked Bobb what had happened. In that moment, all the law school lectures about Miranda rights and the wisdom of staying silent when questioned by the police evaporated. Bobb told them his story, they believed him, they asserted jurisdiction. And they let him go.

One police officer had threatened to derail his life; another gave it back.

"That one incident crystallized for me all of the power of the police, of how much this was my word against the officer's, of how easily this could have gone awry and of how serious the consequences would have been for me," Bobb says. "And I was a white college kid. What if I had been black? Or what if the Berkeley police had not come by?"

AFTER LEAVING BERKELEY, Bobb began the long process of building a career. He clerked for a federal judge, then joined a major law firm and developed a growing list of admirers who valued his work as a careful, methodical litigator. His specialty was anti-trust law, and most of his clients were corporations.

Given that specialty, Bobb's practice didn't demand that he know much about police work, but when Christopher and John W. Spiegel, another leading Los Angeles lawyer, asked him to help analyze the LAPD, he accepted.

Soon Bobb was whiling away his spring in the basement of Parker Center, the city's decaying green-glass and steel police headquarters. With a police guard eyeing his every move, Bobb thumbed through one LAPD personnel file after another. He was not allowed to take the files from the room, so he and other lawyers came back day after day, trying to determine whether citizen complaints and lawsuits were properly investigated.

He was one of many who contributed to the final document, formally entitled "Report of the Independent Commission on the Los Angeles Police Department" but forever known as the Christopher Commission report.

And it was with pride, nervousness, and anticipation that Bobb watched Christopher and other leaders of the commission release their findings to a city on the edge. The report's conclusions were stark:

"There is a significant number of officers in the LAPD who repetitively use excessive force against the public and persistently sistently ignore the written guidelines of the department."

"The LAPD has an organizational culture that emphasizes crime control over crime prevention and that isolates the police from the communities and the people they serve. This style of policing produces results, but it does so at the risk of creating a siege mentality."

"The depar" The department needs to acknowledge that there is in fact a serious problem (of racism and bias) that need to be confroned."

"Chief Gates has served the LAPD and the city for 42 years, the past 13 years as Chief of Police. He has achieved a noteworthy record of public service in a stressful and demanding profession. For the reasons set forth in support of the recommendation that the chief of police be limited to two five-year terms, the commission believes that commencement of a transition in that office is now appropriate."

With those and other conclusions, police reform in Los Angeles had a bible. In the coming months, it would gather momentum and spread and Bobb would increasingly be thrust to the center of it. The County Board of Supervisors, impressed by the Christopher report and concerned about similar problems in the sheriffs department, convened its own commission. Judge James Kolts was named to oversee it, and Merrick Bobb was selected as its general counsel.

With Kolts's backing, Bobb bore down on the sheriffs department with the skill that would become his trademark. Soft-spoken but unyielding, polite but skeptical, methodical, precise, and careful, Bobb demands action without ever seeming demanding. It makes him a deceptively powerful adversary.

"Merrick is tremendously effective," said Raymond C. Fisher, president of the city's civilian Police Commission and a former deputy general counsel to the Christopher Commission. "He is careful, diligent, and persistent. That has served him well."

The Kolts report bore the earmarks of Bobb's influence. It was as direct as the Christopher report. Although its language was diplomatic, its conclusions were equally unflinching. Brutality, the Kolts report said, was too frequent. Prosecutions of wayward deputies were too few. Lawsuits too common and costly.

"Within the [sheriffs department]," the Kolts report and its general counsel concluded, "there is deeply disturbing evidence of excessive force and lax discipline."

That was July 21, 1992. As of that day, Los Angeles had its blueprints for law enforcement reform. And it had all the incentive a city and county could want: the smoldering wreckage of shops, strip malls, and stereo stores, looted and burned in the riots that had torn through the city just three months earlier.

As a lawyer to one commission and as chief counsel to the other, Bobb stood at the center of an exploding civic debate. The studies had revealed deep problems. Now the task was to solve them.

Unlike the Christopher Commission, which did its report and then dissolved, the Kolts Commission left a lingering representative. Bobb agreed to serve as special counsel to the county and to provide regular updates on the status of reform at the sheriffs department. Sheriffs officials say that his presence is a mixed blessing. They both dread and appreciate his reports"The days before one comes out is a tense day around here," assistant sheriff Mike Graham jokingly concedes but they acknowledge that Bobb's influence has profoundly shaped the development of the department.

Not everyone is a fan. But then, you can tell a lot about a man by the enemies he makes. One of Bobb's critics, if not enemies, is former LAPD chief Daryl Gates. "Here's a guy who's made a career out of misinformation," says Gates, who remains deeply bitter about Bobb and the reform movement more broadly. "As a taxpayer of the city of Los Angeles, I resent the hell out of it. I have to pay for that idiot."

And as for the nation's taxpayers? They look to L.A. and wait anxiously. Every day, it seems, a new police department is in trouble. The New York Police Department has helped shepherd a historic drop in crime, but is facing new lawsuits and complaints about use of force by its officers. Philadelphia is racked by corruption Same with New Orleans. Indianapolis and Denver have their problems. The list goes on. "Everywhere you look," says Bobb. "It's part of the general story of what happens in large, urban areas. It's part of a story we all know."

A run-in with an Oakland cop almost derailed his life. Today Merrick Bobb wields power over the police.

JIM NEWTON is a reporter for The Los Angeles Times, where he covers city hall.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryWorries of a Premed

June 1997 By Tyler Stableford '96 -

Feature

FeatureMountain of Ghosts

June 1997 By WD. Wetherell -

Article

ArticleOf Appointments and Disappointments

June 1997 By "E. Wheelock." -

Article

ArticleA Cubicle of One's Own

June 1997 By Noel Perrin -

Class Notes

Class Notes1993

June 1997 By Christopher K. Onken -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

June 1997 By Brooks Clark

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Alumni Council's 50th Year

JULY 1963 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWe were Stardust, We were Golden

October 1993 By David Prentice '69 -

Feature

FeatureTHE 5 MINUTE GUIDE TO THE COLLEGE GUIDES

Nov/Dec 2000 By JON DOUGLAS '92 & CASEY NOGA 'OO -

Cover Story

Cover StoryNO HOLDS BARD

MARCH 1994 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeatureTHE FIRST FIFTY YEARS

OCTOBER 1963 By SIDNEY C. HAYWARD '26 -

Feature

FeatureQuebec in the Modern World

JULY 1964 By THE HON. JEAN LESAGE, LL.D.