Charles Collis Professor of HistoryChair; Latin American and Caribbean Studies

WHEN I ENTERED Dartmouth in 1982, David McLaughlin had taken over the reins of the College from John Kemeny, The Preppie Handbook was required reading, and the word "yuppie" was about to be soundbitten onto the minds of a generation. It was Reagan's America, but I was still a romantic. I expected college to be an intellectual battleground along the lines of Berkeley or Kent State. When I arrived at Dartmouth from my native Montana, in what I considered to be a particularly jaunty military fatigue jumpsuit, I might just as well have been coming from Mars.

I said at the time that I was having a hard time being a woman at Dartmouth, but what was more true is that I had a hard time being a Dartmouth woman—that confident, comfortable corollary of the Dartmouth man: hard-working, athletic, pleased just to be there. (And where the hell did the women all get those bulky blue sweaters with the white dots all over them? Had they been issued in secret before I arrived?) The fact is, I wasn't at all sure I could survive. And then I met Marysa Navarro.

I knew just by looking at her that she was an agitator. Her hair was graying even then, but she got angry and she laughed loudly. She was passionate. At the time, she was the chair of the history department, and it was common knowledge on Webster Avenue that she was a tough grader. She made the frat boys nervous, and I liked her for it. If this Argentinian native could survive Hanover, then I damn well could.

I didn't take an elective with Navarro until my senior year, but in fact her presence was everywhere. Indeed, I learned that I owed my presence at Dartmout in no small part to her. I had her for "Women and Revolution in the Third World," which she team-taught with Leo Spitzer. The class proved to me that Dartmouth was not the myopic country club I'd been fond of denouncing.

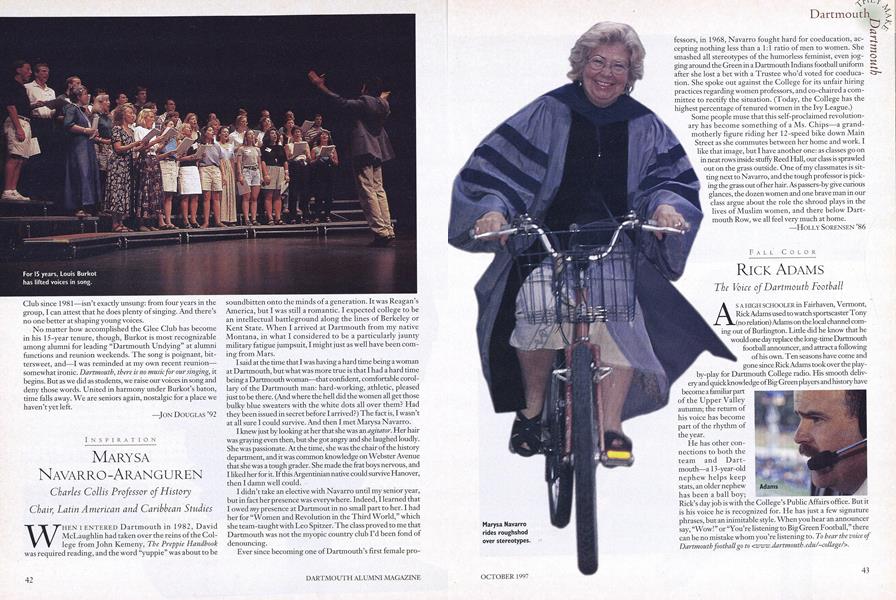

Ever since becoming one of Dartmouth's first female professors, in 1968, Navarro fought hard for coeducation, accepting nothing less than a 1:1 ratio of men to women. She smashed all stereotypes of the humorless feminist, even jogging around the Green in a Dartmouth Indians football uniform after she lost a bet with a Trustee who'd voted for coeducation. She spoke out against the College for its unfair hiring practices regarding women professors, and co-chaired a committee to rectify the situation. (Today, the College has the highest percentage of tenured women in the Ivy League.)

Some people muse that this self-proclaimed revolutionary has become something of a Ms. Chips—a grandmotherly figure riding her 12-speed bike down Main Street as she commutes between her home and work. I like that image, but I have another one: as classes go on in neat rows inside stuffy Reed Hall, our class is sprawled out on the grass outside. One of my classmates is sitting next to Navarro, and the tough professor is picking the grass out of her hair. As passers-by give curious glances, the dozen women and one brave man in our class argue about the role the shroud plays in the lives of Muslim women, and there below Dartmouth Row, we all feel very much at home.

Marysa Navarro rides roughshod over stereotypes.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

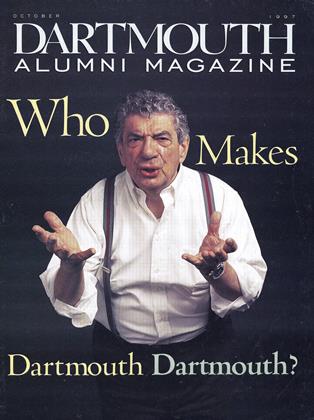

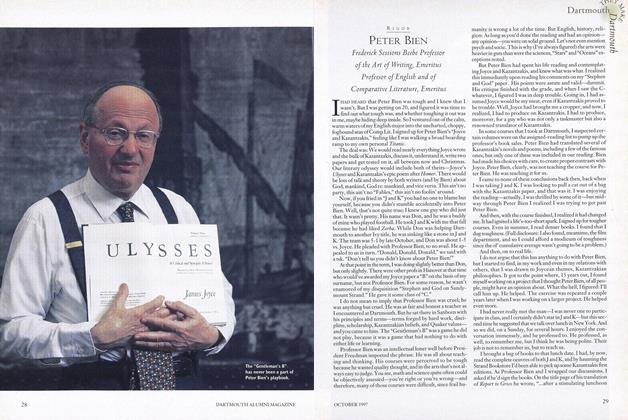

Cover StoryPeter Bien

October 1997 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryM. Lee Pelton

October 1997 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Cover Story

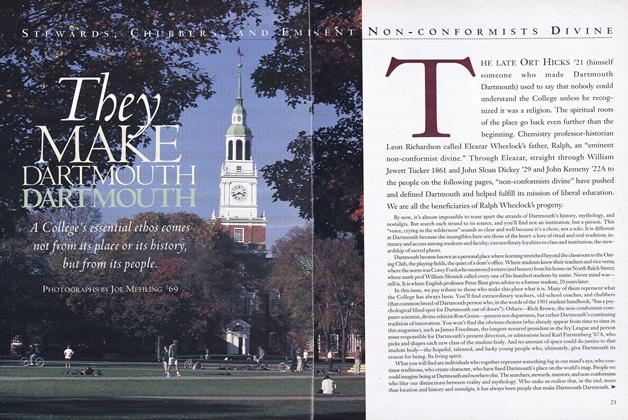

Cover StoryThey Make Dartmouth Dartmouth

October 1997 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWilliam Cook

October 1997 By Heather McCutchen '87 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryChris Miller '97

October 1997 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryDartmouth Dogs

October 1997 By Robert Nutt '49

Holly Sorensen '86

Features

-

Feature

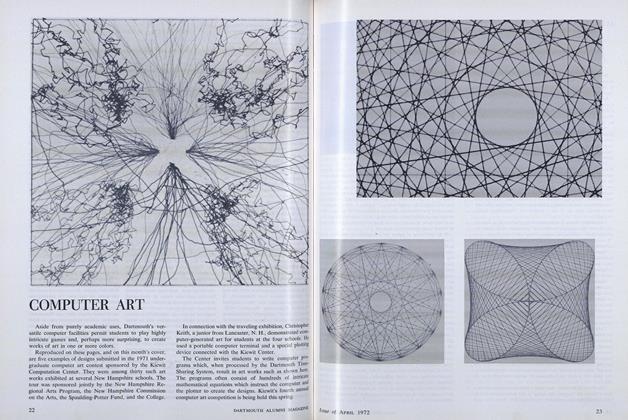

FeatureCOMPUTER ART

APRIL 1972 -

Feature

FeatureTHE HUNTERS, OR THE SUFFERINGS OF HUGH AND FRANCIS, IN THE WILDERNESS.

January 1975 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO MOLD YOUR CHILD INTO IVY MATERIAL

Jan/Feb 2009 By HOWARD GREENE '59 AND SON MATTHEW GREENE '90 -

Feature

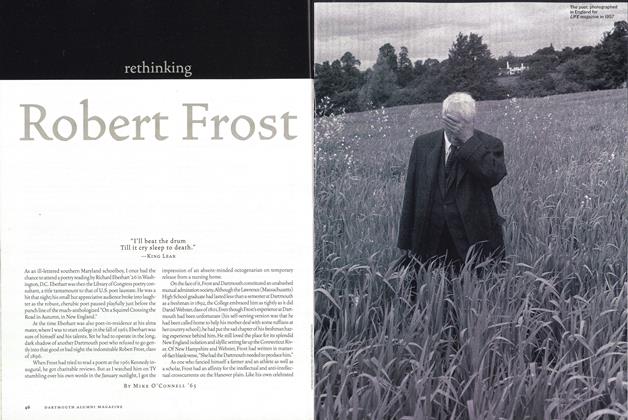

FeatureRethinking Robert Frost

Nov/Dec 2003 By Mike O'Connell ’65 -

Feature

FeatureThe First 25 Years of the Dartmouth Bequest and Estate planning Program

September 1975 By Robert L. Kaiser '39 and Frank A. Logan '52