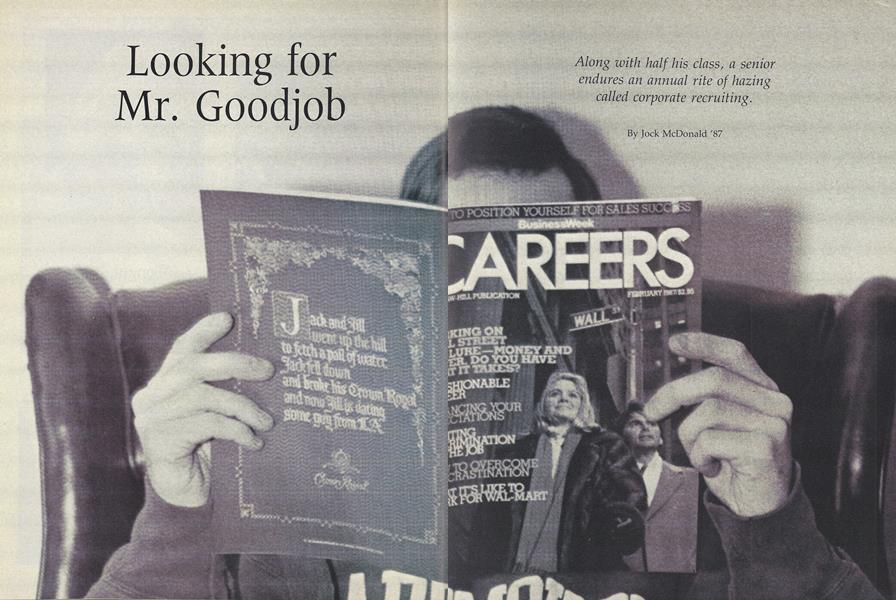

Along with half his class, a senior endures an annual rite of hazing called corporate recruiting.

December 12, 1986: I have been waiting in line in the basement of McNutt Hall for more than half an hour to get my resume laser printed. I want to go home. Exams are two days behind us, and this is supposed to be Christmas break. But for me and for what seems like the entire senior class, the first days of break are spent in Hanover finishing up resumes and writing cover letters.

Then there's the really hard part: in order to go through corporate recruiting, students are required to list their ten favorite companies among those that come to Dartmouth in January and February. The Career and Employment Services office has a rich supply of information on all the companies, but there is more to a preference list than research. There is strategy. Everyone will be signing up for interviews with the big advertising agencies and consumer product agencies. To get treated equally with the hordes of other applicants, I'll put a company like Procter and Gamble high on my list. On the other hand, a technical writing position at a small computer software firm might barely fill a recruiter's day of 14 interviews. I'll put the job lower on my list.

Finally, my resume comes out of the printer; a couple of hours later, CES approves my preference list. Just in time, too. The janitor, brandishing a mop, chases me out of the dorm and locks the door behind me. I drive home, wondering how I got wrapped up in this corporate recruiting scene in the first place. "There is only one disservice that many students do themselves," says Skip Sturman '70, director of CES. "It is the tendency to let others determine what is best for you."

That's easy for him to say. But when all your friends are down at CES, where else can you go to socialize? Corporate recruiting becomes as much a social thing as a personal challenge. Besides, the mixture of recruiting organizations leans toward the corporate. Sure, there is a social service agency here, an educational recruiting firm there, but most of the companies hail from a small family of fields. Banks, investment and commercial. Advertising. Computer science. Consulting. Consumer products. Insurance. Pharmaceuticals. Accounting. Retailing.

Most of the prestigious companies arrive on campus in the fall, armed with impressive presentations and hors d'oeuvres catered by the Hanover Inn (some of us would call the lavish platters meals). In the winter, corporate recruiting dominates CES, forcing all other careers to cower in the shadows. (The food has mysteriously disappeared by this time; it is our turn to impress.)

The recruiters many of them cocky recent graduates strut in and out of the interview rooms, delighted to be on the other side of the desk. Nervous seniors sit and stand awkwardly in their new suits, fidgeting with the company literature they are supposed to know by heart. About half the senior class, 500 people, have at least one interview through corporate recruiting. More than 200 have five or more interviews among the 146 organizations that travel to Hanover from as far away as California or as close as down the road a mile or two.

January 4: I return after a Christmas break spent researching careers. I'm still trying to decide where I would best fit in. Advertising? Brand management? I have ruled out banking and consulting, but insurance and retail need a closer look.

I unlock the door to my room and log on to the computer. Instant good news: the CES database has my name on the first access list for several of the companies I wanted! Getting onto a first access list means I am guaranteed an interview with a company, while second access means I would have to wait and see if any slots open up. The second-access slots are first-come, first-served. This is when the camping begins. The CES staff was surprised at the earnestness of this year's class. A friend of mine camped out beside the office door from five in the afternoon until 8:30 the next morning. She got her interview in fact, she had no competition in line until about 4 a.m.

Sometimes, on the other hand, people get interviews on the spur of the moment. Campus legend has it that, to fill a cancelled slot, one student got pulled off the snow sculpture with a wad of tobacco in his jaw.

Evening: I strut up and down the dorm hallway to practice looking comfortable in my new suit and fishing for reactions, I admit. The underclassmen on my hall gather around me, looking worried. One asks, "Are you getting married or something?"

January 12: First day of interviews. I go directly to CES. I am not signed up for any interviews yet, but I want to see what's going on. A friend emerges from an interview for an editorial position with a small consulting firm. "You've got to grab an interview," she tells me. "You'd thrive at this job."

So I go to Mary Oronte, recruiting coordinator and cheerful student-sanity maintenance person. Like magic, she lifts my resume out of the file cabinet and hands it to the interviewer from the consulting company, who already has a busy schedule. "Fifteen minutes," she whispers to me. I sprint back to my room and throw myself into my suit. And now here I am in the hot seat for the first time, cotton-mouthed, knowing almost nothing about the company.

A suit attracts other seniors like flies to candy. "Who was it with? How did it go?" they ask me afterward. I don't want to talk about it.

Afternoon: I call a recent Dartmouth graduate who works at Procter and Gamble and ask her questions about Brand Management for my upcoming interview. At one point I have to shuffle my notes to find a fact. She gasps, "You mean you haven't memorized it all yet?"

January 14: Procter and Gamble day. I sit in my room all morning reviewing notes and preparing my strategy. It pays to be ready, CES tells us constantly. A friend of mine has been signing up for every interview she can get. Her schedule is so tight (occasionally she even tries to make it to class) that she doesn't have time to bone up on the companies. She obtained one interview with what at first glance appeared to be a financial analyst training program. She sat down in the interview room and answered the basic first question, "Tell me a little about yourself." Then the recruiter asked her, "Now explain how you decided to be a trader."

She froze. A trader! Her mind raced back to what she had already answered, hoping she hadn't mentioned anything specific about analyst positions. She spewed out some generic comments about challenges and responsibility.

On the other hand, one can be over- prepared. I have already learned that early morning interviews go better for me. Jumping straight into a suit in the morning is more comfortable than changing into one after being in casual clothes. Also, interviewing early leaves little time to get the jitters. My slot with Procter and Gamble is in the afternoon. I am scared to death.

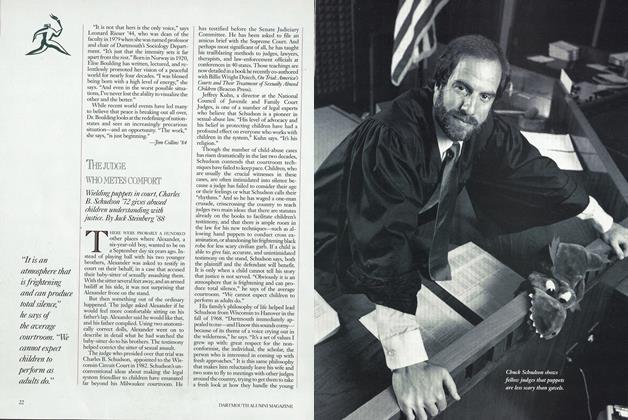

Afternoon: I arrive at CES 20 minutes early, as advised, and sit stiffly on the couch. Senior women walk in wearing suits and L.L. Bean boots, heels in hand. All the guys have on conservative grey or blue suits, white shirts, red or sometimes yellow print ties, mostly wing-tipped footwear. We look like some sort of clone factory; no wonder it's hard for recruiters to make hiring decisions.

The office buzzes with recruiters who emerge from interview rooms like trapdoor spiders, finding their prey and shepherding them into the cells. Whenever one emerges, all eyes rise to witness the greeting: the name called out, the standing up from the couch, the hello, the all-important handshake, the how are you today, and the disappearance into the chamber.

To ease some of the tension there is Burt Nadler, associate director of CES and Dartmouth's head of corporate recruiting. He makes sure we take all of this very seriously, but there is a rebellious streak in him. For one thing, he wears a Mickey Mouse watch with his exquisite suits. And he combines an unvarying deadpan expression with a wicked sense of humor. One time an interviewer from New York Telephone a former AT&T company came out of his cubicle and asked Burt if he could make a phone call. Sure, said Burt, just dial 9 and your MCI number. The guy didn't get the joke, and Burt had to poke his head through the door and explain that he was kidding, it was all right to use AT&T. We seniors tried not to snicker, and we all felt better about ourselves.

On the wall, next to a growing list of lost coats and found boots, is a page for graffiti. Someone has written a short dialogue:

Interviewer from Salomon Brothers: So, why don't you have a 4.0 GPA? Student: Well, why aren't you working at Goldman Sachs?

Time creeps like the sweat down my back. Ten minutes to go. Sitting next to me on the couch is a student with an employment application. "List your hobbies," he reads aloud. He contemplates writing "Job interviews" in response, then thinks better of it. A woman paces back and forth. "I can't sit down," she says, gazing distractedly at a lacquered nail. "First, because my skirt sticks to me. Second, because I'm so nervous. Do I have too much makeup on?"

Sitting opposite me is my friend Landon Gates, a lanky, blond engineering student from California. He plans to spend a year in Australia but he's interviewing for the experience of it. He says to me in a stage whisper, "Wouldn't it be scary if somebody actually offered me a job?"

My turn: a corporate face pops out, I jump up, my hands feeling strangely enormous. I am swept into a tiny room where the winter sun glares right into my face. An interviewing trick? I endure it. Suddenly time speeds up and the session blurs by: what are your goals what is it about Procter and what do you see yourself decisions creative opportunity and I am back in the waiting room.

"How'd it go?" "I don't want to talk about it." January 23: The rejections, or "ding" letters, start coming in. Procter and Gamble shoots me down while a good friend gets a callback inviting her to corporate headquarters in Cincinnati. I try to act delighted, feeling like a lump in a flour sifter.

January 26: The phone jolts me awake. It is CES, inviting me to fill a cancelled slot with an ad agency. I climb into my suit, which is actually starting to feel familiar. I throw my tie into a perfect knot, the tip just kissing my belt buckle. That is one skill I've perfected during these last few weeks.

I go into the interview feeling confident, and hit the jackpot: my interviewer was a former rower here, like me, and was an intern with the AlumniMagazine, like me. I feel relaxed maybe too relaxed. I get chatty and lose track of the things I am supposed to be proving. I must convey the message themessage that advertising has been an obsession with me since birth, regardless of the truth. I walk out feeling too good, which is an ominous sign.

David Wiser, an ambitious senior, had a different experience: he was called to the agency's Chicago office for second-round interviews. He was taken out to lunch by a young account executive who, he was told, was deaf. During lunch he shouted at her in the restaurant to make himself heard, feeling keenly embarrassed. Back at the office, everyone was laughing. It was all a prank the same prank they had played on the interviewer when she had been called back a few years earlier. David later received an offer.

February 25: Friends are flying to Chicago and New York and spending two glorious nights in a good hotel, everything on the company tab. But there is a price: as many as nine interviews in one day, one of them a stress interview.

This is where the recruiter probes little holes in the applicant's resume and opens them up with a rhetorical sledgehammer: "Tell me all the ways you find yourself using differential equations."

No plane rides or hotels for me yet, though I was called back for a day of interviews with a small consulting firm in New Haven and for a technical writing position with a computer software company outside Boston. I sat down to take a writing test at the software company, and immediately panicked when handed one of those rulers with different shaped holes cut out. I scanned the sheet in front of me for the culprit question: flowchart a computer program that will ask for a list of whole numbers and show their sum. It should have been easy, but it has been over three years since my last experience with programming. I found out later that the same test is given to potential software engineers. That news made lunch at a Chinese restaurant with my interviewer much more pleasant.

March 2: No offers yet, but a strong nibble or two. Like Landon Gates, I think, "Wouldn't it be scary if somebody actually offered me a job?" As oncampus interviews slow to a trickle, I begin making plans to continue the job search on my own. And why not? I've gotten pretty good at this. I may even be starting to like it.

March 9: Ding letters cover the doors in my fraternity. Most of the notes are generic, and they often contain typos and grammatical errors. That makes us all feel better about our own newly public inadequacies. Many of the letters have lines crossed out and replaced with more honest statements. A line like, "Your qualifications are strong, but our needs are limited," is altered to read: "We wouldn't hire you even if nobody else applied. Your resume has been forwarded to the sanitation department."

On the other hand, many of my friends who went through recruiting are now walking around with shining faces. The friend who got the callback with P&G starts with the company in August. A fraternity brother has landed Kidder Peabody; a dormmate has been accepted by an ad firm. A few seniors are in agony: how do they choose among the handful of offers? One guy I know kept going to interviews even after he secured the offer he wanted, just so he could tell everyone how many companies loved him.

And for me? There is a slightly bitter taste in my mouth, after all this, of having swallowed something good for me. And it was.

April 10: If nothing turns up from on campus recruiting which looks increasingly likely that won't be so bad, I tell myself. When I do finally get a job it will be one I truly want, because I will have gone out and found it myself. In a way, the superstars in my class are missing something. Between corporate recruiting now and flirting with headhunters in the future, some of them will never have the

opportunity to go through some real soul searching. Sure, they will make lavish salaries right from the start. And they will be given astonishing responsibility early on. And their first jobs may be filled with the creativity that makes a liberal arts graduate salivate. But what is all that compared to a thoughtful, self-initiated search into the harsh realities of unemployment?

I don't want to talk about it.

At press time, Jock McDonald was stillhunting.

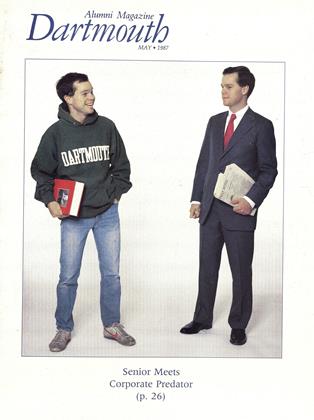

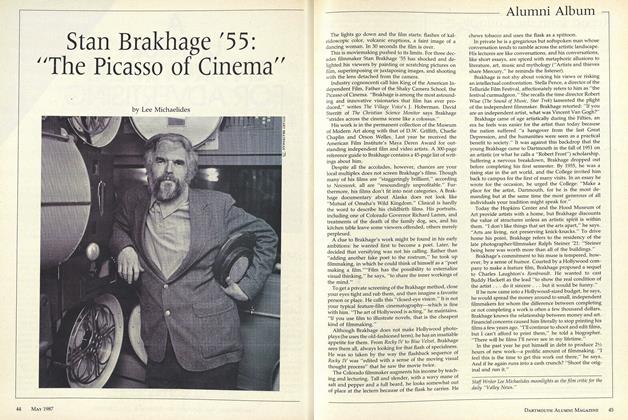

The UniformWith hard-earned ease, Jock knots the requisite yellow print tie (left). Meanwhile, asoberly dressed Erin Foster tromps to aninterview (right).

Corporate Animal"I've gotten pretty good at this," says jockof his hunting skill. "I may even be startingto like it."

We look like some sort ofclone factory; no wonderit's hard for recruiters tomake hiring decisions.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Spanish Galleon's Real Treasure

May 1987 By R. Duncan Mathewson III '60 -

Feature

FeatureThe Uncompetitive Society

May 1987 By Richard D. Lamm -

Feature

FeatureThe Official Dartmouth Reunion Guide to Greenspeak

May 1987 -

Sports

SportsA Fast-Balling Junior Mulls Going Pro

May 1987 By Jim Needham -

Article

ArticleStan Brakhage '55: "The Picasso of Cinema"

May 1987 By Lee Michaelides -

Class Notes

Class Notes1983

May 1987 By Kenneth M. Johnson