So help me, Herodotus how can I trust history? By Christine Schultz

LET US BEGIN, as James Tatum does, with an exercise. Imagine a particular event involving persons of your choosing. Now, if you would, jot two separate accounts of that one event. In the first, you may fictionalize. In the second, record history. The point, you see, is that the narrative art is similar in both. Perhaps even the same. The word history, in fact, is etymologically related to the word story. So how can we know which holds truth and which falsehood?

From as early as 700 B.C., the poet Hesiod was concerned with lies and truth-telling. He wrote the first word on the subject. It comes down to us through the muses of Helicon in Theogony:

Shepherds who dwell in the fields, base creatures, disgraces, mere bellies,

We know how to tell numerous lies which seem to be truthful,

But whenever we wish, we know how to utter the full truth.

How far have we come in our understanding of such things since then? That is the central question of classics professor Tatum's course "Lying and Trudi-Telling in History and Fiction." Through texts such as Herodotus, Nabokov, and Morante, the discussion takes shape. "We were looking at various things on the borders of what people think history is and what fiction is," says Tatum. "You find quite often that the borders are very hard to patrol."

The borders have been blurred since the fifth century B.C., when Herodotus first staked a new science from the muddy waters of the story-telling tradition. The word "history" itself was Herodotus's invention. He used it to mean inquiry or investigation. The historian, by extension, became the inquirer, the inspector of firsthand evidence. The moment marked a radical change from the poets' tradition, and in making the break, Herodotus and his successors were forced to say first what history was not.

"History is not interested in what the poets say, it is not interested in hearsay," says Tatum. From that break came another profound change in how stories got made and told. The traditional poetry, songs, and myths once created by the culture's muses had been known and shared by everyone; now they became individually researched productions, historical accounts based on personal investigation, written by and attributed to one academic only.

That was quite a shift from traditional cultures in the Mediterranean world, especially the oral culture where things like the Homeric songs were passed down by hearing and remembering.

The difficulty, from the start, was that history demanded exactitude; if the historian relaxed his standard, he'd slip back into mythmaking. "You can see the struggle in the temperament of historians," says Tatum. "They don't like the intrusion of the fictive and the made-up. Whereas a poet, or a short-story writer, or a novelist says manipulate the facts anyway you want."

So what is truth? The word "true" to the ancient Greeks meant that which is not forgotten; that which is worth remembering. But the truth of history in the days of the ancients was harder to get at than it is today in the age of information. The ancients were limited by sources; there were no transcripts, no libraries, no documentary evidence. What the ancient historians did was make a best guess at what someone probably said in any given circumstance. History by rhetoric. It was as close to history as they got.

There was a natural antagonism between fiction writers and historians, and so it was bound to come about that the fiction writers would take the historians' uncertainty and run with it. In Pale Fire Vladimir Nabokov made a wonderful spoof of the academic historian's mind."Pale Fire is one of the funniest books you'll ever read," says Tatum. "The students and I were just beside ourselves. It's a god-awful poem with 999 lines, and commentary. By the time you get through, you realize that this seeming scientific historic inquiry is a product of a deranged mind. It takes a great level of genius to reach that level of banality."

So why is it that of the people all living at the same time some make history and some poetry? Tatum's students considered that question by comparing the thoughts and practices of the real, live historians Charles Wood and Allison Frazer, the fiction writers Ernest Hebert and Jay Parini, and the poet Cleopatra Mathis, who all came to speak to the class.

"They were all excellent at showing the students the play of imagination and intelligence that's the fire behind the works," says T atom, "and how much of that has to go on before even a little thing is produced."

In his work, Dartmouth historian Charlie Wood, for instance, deals with die famous historic figures who everybody thinks they know, such as Joan of Arc and Richard HI, and takes apart the myths to get at the historical realities. "The Richard III we know," says Wood, "is Shakespeare's hunch-backed toad, his nasty Machiavelli." He is not just evil incarnate; rather, he is a stunningly brilliant, incarnation of that evil, a man who knows not just himself, but also exactly what steps to take that will win him the crown. "What I think the historical facts actually demonstrate, though, is that Richard was a person of limited intelligence, one who lacked the skills needed to attract other human beings to his side, a person who might know how to address a concrete military crisis, say, but who had no idea how to deal with less definable problems relating to human trust."

Cleopatra Ma this, as a poet, works largely in reverse; she takes realities and makes myth. Many real people across many decades of her life may come together to make one fictitious composite character in one of her poems. "That's what poets do," says Tatum. "They aim for something that isn't tied to specific incidents, but is transcendent. The truth a poet has is universal truths worth maintaining."

"The ancients would not have found the doctrine that history itself is a fiction particularly surprising, inasmuch as they drew only a faint line between myth and history and considered the writing of history rhetorical work." So says G.W. Bowersock in History as Fiction: Nero to Julian. And so says Tatum: "All this course is doing is trying to get through the bureaucratic organization of thinking to try to re-establish connections, not to lead to confusion, but just to see that there is that kind of struggle there."

In both history and fiction there is continuity. From Herodotus in the fifth century B.C. to Nabokov in the twentieth, the issue of boundaries between fiction and history, between lying and truth-telling, between deliberately lying and deliberately not lying come up time and again. "The problem lies not so much in the struggle over the boundary," says Tatum, "as in the tidy dividing mind that insists the two are so separate as to be unrelated."

CHRISTINE SCHULTZ writes some truth and some fiction from Taylor, Mississippi.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryDartmouth on Mount Washington

November 1997 By Tyler Stableford '96 -

Feature

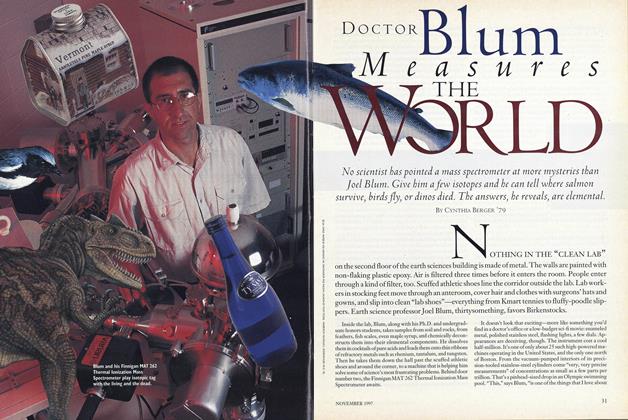

FeatureDoctor Blum Measures the World

November 1997 By Cynthia Berger '79 -

Feature

Feature"Hi. My Name's John. I'm a Zero."

November 1997 By Jeanhee Kim '90 -

Article

ArticleThe President Steps Down

November 1997 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleThe Collis Silverware Mystery

November 1997 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleLiving Well by Doing Good

November 1997 By James O. Freedman