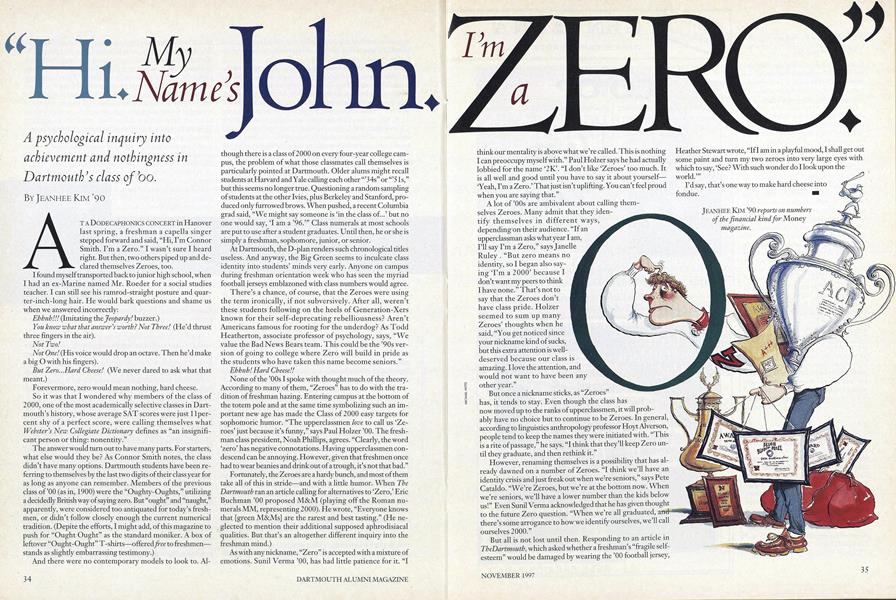

A psychological inquiry into achievement and nothingness in Dartmouth's class of bo.

TA DODECAPHONICS CONCERT in Hanover last spring, a freshman a capella singer stepped forward and said, "Hi, I'm Connor Smith. I'm a Zero." I wasn't sure I heard right. But then, two others piped up and declared themselves Zeroes, too.

I found myself transported back to junior high school, when I had an ex-Marine named Mr. Roeder for a social studies teacher. I can still see his ramrod-straight posture and quarter-inch-long hair. He would bark questions and shame us when we answered incorrectly: Ehhnh!!! (Imitating the Jeopardy! buzzer.) You know what that answer's worth? Not Three! (He'd thrust three fingers in the air).

Not Two! Not One! (His voice would drop an octave. Then he'd make a big O with his fingers).

But Zero...Hard Cheese! (We never dared to ask what that meant.)

Forevermore, zero would mean nothing, hard cheese. So it was that I wondered why members of the class of 2000, one of the most academically selective classes in Dartmouth's history, whose average SAT scores were just 11 percent shy of a perfect score, were calling themselves what Webster's New Collegiate Dictionary defines as "an insignificant person or thing: nonentity."

The answer would turn out to have many parts. For starters, what else would they be? As Connor Smith notes, the class didn't have many options. Dartmouth students have been referring to themselves by the last two digits of their class year for as long as anyone can remember. Members of the previous class of '00 (as in, 1900) were the "Oughty-Oughts," utilizing a decidedly British way of saying zero. But "ought" and "naught," apparently, were considered too antiquated for today's freshmen, or didn't follow closely enough the current numerical tradition. (Depite the efforts, I might add, of this magazine to push for "Ought Ought" as the standard moniker. A box of leftover "Ought-Ought" T-shirts—offered free to freshmen stands as slightly embarrassing testimony.)

And there were no contemporary models to look to. Al-though there is a class of 2 000 on every four-year college campus, the problem of what those classmates call themselves is particularly pointed at Dartmouth. Older alums might recall students at Harvard and Yale calling each other "'34s" or "'51s," but this seems no longer true. Questioning a random sampling of students at the other Ivies, plus Berkeley and Stanford, produced only farrowed brows. When pushed, a recent Columbia grad said, "We might say someone is 'in the class of...' but no one would say, 'I am a '96.'" Class numerals at most schools are put to use after a student graduates. Until then, he or she is simply a freshman, sophomore, junior, or senior.

At Dartmouth, the D-plan renders such chronological titles useless. And anyway, the Big Green seems to inculcate class identity into students' minds very early. Anyone on campus during freshman orientation week who has seen the myriad football jerseys emblazoned with class numbers would agree.

There's a chance, of course, that the Zeroes were using the term ironically, if not subversively. After all, weren't these students following on the heels of Generation-Xers known for their self-deprecating rebelliousness? Aren't Americans famous for rooting for the underdog? As Todd Heatherton, associate professor of psychology, says, "We value the Bad News Bears team. This could be the '90s version of going to college where Zero will build in pride as the students who have taken this name become seniors." Ehhnh! Hard Cheese!!

None of the '00s I spoke with thought much of the theory. According to many of them, "Zeroes" has to do with the tradition of freshman hazing. Entering campus at the bottom of the totem pole and at the same time symbolizing such an important new age has made the Class of 2000 easy targets for sophomoric humor. "The upperclassmen love to call us 'Zeroes' just because it's fanny," says Paul Holzer '00. The freshman class president, Noah Phillips, agrees. "Clearly, the word 'zero' has negative connotations. Having upperclassmen condescend can be annoying. However, given that freshmen once had to wear beanies and drink out of a trough, it's not that bad."

Fortunately, the Zeroes are a hardy bunch, and most of them take all of this in stride—and with a little humor. When The Dartmouth ran an article calling for alternatives to 'Zero,' Eric Buchman '00 proposed M&M (playing off the Roman numerals MM, representing 2000). He wrote, "Everyone knows that [green M&Ms] are the rarest and best tasting." (He neglected to mention their additional supposed aphrodisiacal qualities. But that's an altogether different inquiry into the freshman mind.)

As with any nickname, "Zero" is accepted with a mixture of emotions. Sunil Verma '00, has had little patience for it. "I think our mentality is above what we're called. This is nothing I can preoccupy myself with." Paul Holzer says he had actually lobbied for the name '2K'. "I don't like 'Zeroes' too much. It is all well and good until you have to say it about yourself'Yeah, I'm a Zero.' That just isn't uplifting. You can't feel proud when you are saying that."

A lot of '00s are ambivalent about calling themselves Zeroes. Many admit that they idetify themselves in different ways, depending on their audience. "If an upperclassman asks what year I am, A I'll say I'm a Zero," saysjanelle Ruley . "But zero means no identity, so I began also saying'l'm a 2000' because I don't want my peers to think I have none." That's not to say that the Zeroes don't have class pride. Holzer seemed to sum up many Zeroes' thoughts when he said, "You get noticed since your nickname kind of sucks, but this extra attention is welldeserved because our class is amazing. I love the attention, and would not want to have been any other year."

But once a nickname sticks, as "Zeroes has, it tends to stay. Even though the class has now moved up to the ranks of upperclassmen, it will probably have no choice but to continue to be Zeroes. In general, according to linguistics anthropology professor Hoyt Alverson, people tend to keep the names they were initiated with. "This is a rite of passage," he says. "I think that they'll keep Zero until they graduate, and then rethink it."

However, renaming themselves is a possibility that has already dawned on a number of Zeroes. "I think we'll have an identity crisis and just freak out when we're seniors, says Pete Cataldo. "We're Zeroes, but we're at the bottom now. When we're seniors, we'll have a lower number than the kids below us!" Even Sunil Verma acknowledged that he has given thought to the future Zero question. "When we're all graduated, and there's some arrogance to how we identify ourselves, we'll call ourselves 2000."

But all is not lost until then. Responding to an article in The Dartmouth, which asked whether a freshman's "fragile selfesteem" would be damaged by wearing the '00 football jersey, Heather Stewart wrote, "If I am in a playful mood, I shall get out some paint and turn my two zeroes into very large eyes with which to say, 'See? With such wonder do I lookupon the world.'"

I'd say, that's one way to make hard cheese into fondue.

JEANHEE KIM '90 reports on numbers of the financial kind for Money magazine. j

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

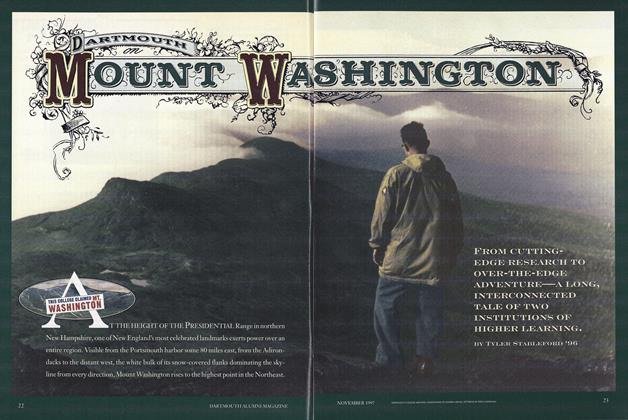

Cover StoryDartmouth on Mount Washington

November 1997 By Tyler Stableford '96 -

Feature

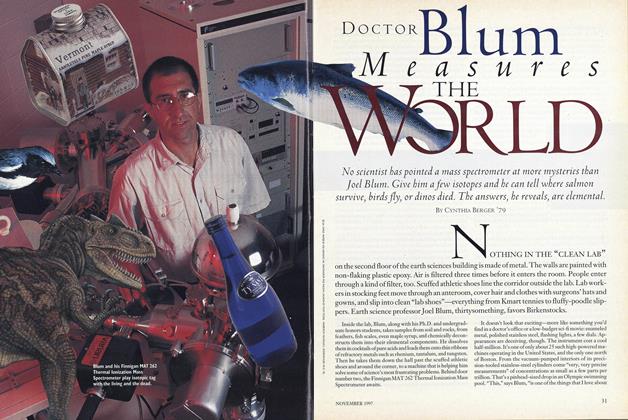

FeatureDoctor Blum Measures the World

November 1997 By Cynthia Berger '79 -

Article

ArticleThe Truth, The Half Truth, and Nothing of the Truth

November 1997 -

Article

ArticleThe President Steps Down

November 1997 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleThe Collis Silverware Mystery

November 1997 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleLiving Well by Doing Good

November 1997 By James O. Freedman

Jeanhee Kim '90

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe End of a Dartmouth Era

OCTOBER 1964 -

Feature

FeaturePro Bono Publico

JANUARY 1973 -

Cover Story

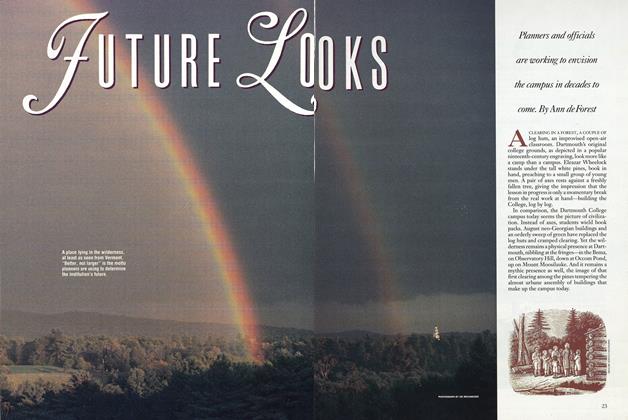

Cover StoryFuture Looks

MAY 1990 By Ann de Forest -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO RAISE HAPPY KIDS

Jan/Feb 2009 By CHRISTINE CARTER '94 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHigher Unhappiness

MARCH 1995 By Frank D. Gilroy '50 -

Feature

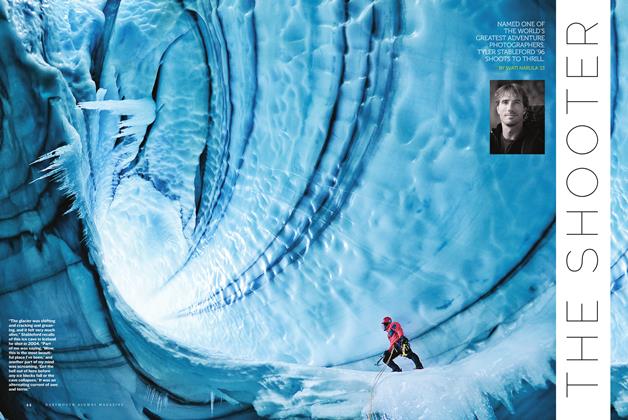

FeatureThe Shooter

Jan/Feb 2013 By Svati Kirsten Narula ’13