Adventurers, nations, and scientists know what they want from Antarctica.

Harsh, empty, and bleak, it is the coldest, windiest, I and highest continent on earth. Like the planets and stars, Antarctica belongs to everyone and to no one. But this remotest of places has long fired the human imagination, stirred the passions of adventurers, spurred nations to arrange joint access, and drawn scientists the world over to pierce its frozen depths.

For scientists like physics professor James LaBelle, who teaches a freshman seminar on Antarctica, the continent functions as a kind of enormous outdoor laboratory. Its massive glacial ice cap rises an average 1.5 miles above sea level (three miles in some spots), and altogether holds 70 percent of the world's fresh water. Yet Antarctica is also one of the world's great deserts, with less annual rainfall than the Sahara. Where no melting has occurred, the ice at the bedrock may be one million years old. Native Antarctic life is limited to a few species of plants, algae, fungi, and mosses. Penguins, seals, whales, and other animals are transients who hardly dare to penetrate the coast. From measuring growth of the ozone hole that admits dangerous ultraviolet radiation through the earth's atmosphere, to examining the record of climatic change over millions of years for evidence of global warming, scientists are looking to the polar continent for answers to some of earth's most pressing problems.

Antarctica is especially suitable for optical astronomy. Remote from human civilization, the continent is relatively free from light pollution and radio emissions, making possible the detection of neutrinos and other sub-atomic particles, as well as a variety of cosmic rays and ionospheric currents. Viewed through Antarctica's high, thin air, even the stars do not twinkle.

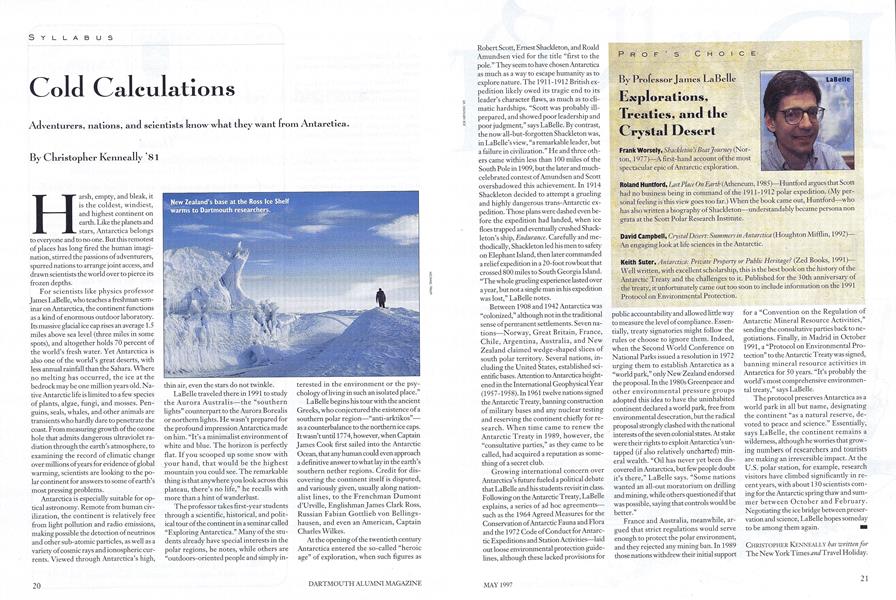

LaBelle traveled there in 1991 to study the Aurora Australis—the "southern lights" counterpart to the Aurora Borealis or northern lights. He wasn't prepared for the profound impression Antarctica made on him. "It's a minimalist environment of white and blue. The horizon is perfectly flat. If you scooped up some snow with your hand, that would be the highest mountain you could see. The remarkable thing is that anywhere you look across this plateau, there's no life," he recalls with more than a hint of wanderlust.

The professor takes first-year students through a scientific, historical, and political tour of the continent in a seminar called "Exploring Antarctica." Many of the students already have special interests in the polar regions, he notes, while others are "outdoors-oriented people and simply interested in the environment or the psychology of living in such an isolated place."

La Belle begins his tour with the ancient Greeks, who conjectured the existence of a southern polar region—"anti-arktikos"— as a counterbalance to the northern ice caps. It wasn't until 1774, however, when Captain James Cook first sailed into the Antarctic Ocean, that any human could even approach a definitive answer to what lay in the earth's southern nether regions. Credit for discovering the continent itself is disputed, and variously given, usually along nationalist lines, to the Frenchman Dumont d'Urville, Englishman James Clark Ross, Russian Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen, and even an American, Captain Charles Wilkes.

At the opening of the twentieth century Antarctica entered the so-called "heroic age" of exploration, when such figures as Robert Scott, Ernest Shackleton, and Roald Amundsen vied for the title "first to the pole." They seem to have chosen Antarctica as much as a way to escape humanity as to explore nature. The 1911-1912 British expedition likely owed its tragic end to its leader's character flaws, as much as to climatic hardships. "Scott was probably illprepared, and showed poor leadership and poor judgment," says LaBelle. By contrast, the now all-but-forgotten Shackleton was, in LaBelle's view, "a remarkable leader, but a failure in civilization." He and three others came within less than 100 miles of the South Pole in 1909, but the later and muchcelebrated contest of Amundsen and Scott overshadowed this achievement. In 1914 Shackleton decided to attempt a grueling and highly dangerous trans-Antarctic expedition. Those plans were dashed even before the expedition had landed, when ice floes trapped and eventually crushed Shackleton's ship, Endurance. Carefully and me- thodically, Shackleton led his men to safety on Elephant Island, then later commanded a relief expedition in a 20-foot rowboat that crossed 800 miles to South Georgia Island. "The whole grueling experience lasted over a year, but not a single man in his expedition was lost," LaBelle notes.

Between 1908 and 1942 Antarctica was "colonized," although notin the traditional sense of permanent settlements. Seven nations—Norway, Great Britain, France, Chile, Argentina, Australia, and New Zealand claimed wedge-shaped slices of south polar territory. Several nations, including the United States, established sci- entific bases. Attention to Antarctica heightened in the International Geophysical Year (1957-1958). In 1961 twelve nations signed the Antarctic Treaty, banning construction of military bases and any nuclear testing and reserving the continent chiefly for research. When time came to renew the Antarctic Treaty in 1989, however, the "consultative parties," as they came to be called, had acquired a reputation as something of a secret club.

Growing international concern over Antarctica's future fueled a political debate that LaBelle and his students revisit in class. Following on the Antarctic Treaty, LaBelle explains, a series of ad hoc agreementssuch as the 1964 Agreed Measures for the Conservation of Antarctic Fauna and Flora and the 1972 Code of Conduct for Antarctic Expeditions and Station Activities—laid out loose environmental protection guidelines, although these lacked provisions for public accountability and allowed little way to measure the level of compliance. Essentially, treaty signatories might follow the rules or choose to ignore them. Indeed, when the Second World Conference on National Parks issued a resolution in 1972 urging them to establish Antarctica as a "world park," only New Zealand endorsed the proposal. In the 1980s Greenpeace and other environmental pressure groups adopted this idea to have the uninhabited continent declared a world park, free from environmental desecration, but the radical proposal strongly clashed with tire national interests of the seven colonial states. At stake were their rights to exploit Antarctica's untapped (if also relatively uncharted) mineral wealth. "Oil has never yet been discovered in Antarctica, but few people doubt it's there," LaBelle says. "Some nations wanted an all-out moratorium on drilling and mining, while others questioned if that was possible, saying that controls would be better."

France and Australia, meanwhile, argued that strict regulations would serve enough to protect the polar environment, and they rejected any mining ban. In 1989 those nations withdrew their initial support for a "Convention on the Regulation of Antarctic Mineral Resource Activities," sending the consultative parties back to negotiations. Finally, in Madrid in October 1991, a "Protocol on Environmental Protection" to the Antarctic Treaty was signed, banning mineral resource activities in Antarctica for 50 years. "It's probably the world's most comprehensive environmental treaty," says LaBelle.

The protocol preserves Antarctica as a world park in all but name, designating the continent "as a natural reserve, devoted to peace and science." Essentially, says LaBelle, the continent remains a wilderness, although he worries that growing numbers of researchers and tourists are making an irreversible impact. At the U.S. polar station, for example, research visitors have climbed significantly in recent years, with about 130 scientists coming for the Antarctic spring thaw and summer between October and February. Negotiating the ice bridge between preservation and science, LaBelle hopes someday to be among them again.

CHRISTOPHER KENNEALLY has written for The New York Times Holiday.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

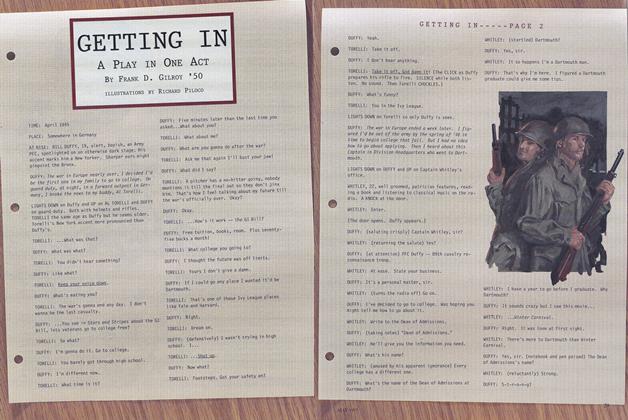

Cover StoryGETTING IN

May 1997 By FRANK D. GILROY '50 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Balance

May 1997 By James Wright -

Feature

FeatureDon't Call Me A Pundit

May 1997 By DIANE CYR -

Article

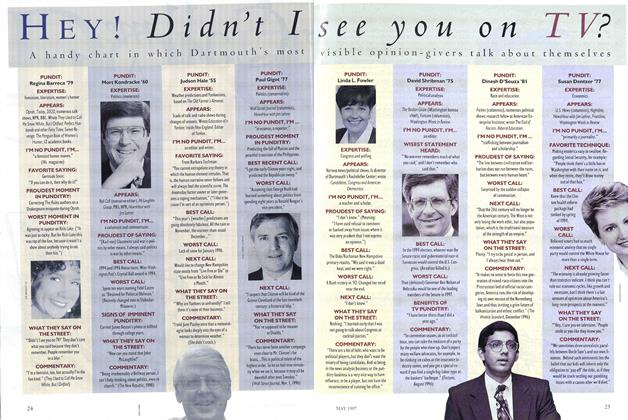

ArticleHey! Didn't I See You on TV?

May 1997 -

Article

ArticleBuildings Spring Up and Athletes Get Down

May 1997 By "E. Wheelock" -

Class Notes

Class Notes1979

May 1997 By Jeffrey Boylan, Jim "Wazoo" Wasz