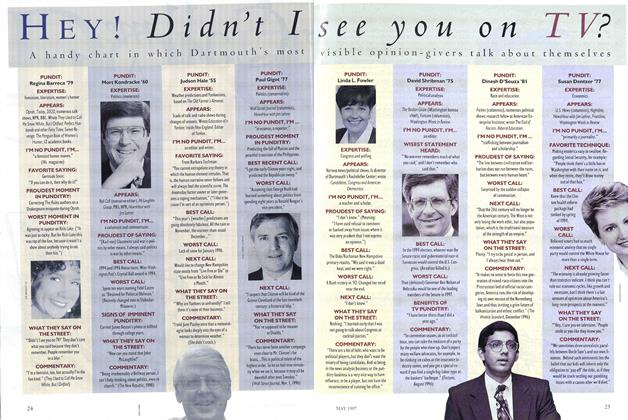

First of all, this article is not punditry. Had this been a piece written by an actual pundit, you would be reading learned opinion, scholarship, wit, and reflective analysis distilled through a distinctive point of view. Instead, this piece is mere journalism, which perhaps can be considered only the soup course of punditry.

It must be said, however, that punditry has acquired a bad rap of late. Consider, for instance, the multitude of "experts" dissecting weirdnesses on Ricki Lake. Consider the talk shows blooming on TV like mold on a shower door. Witness Florence Henderson dispensing opinion on Politically Incorrect.

True pundits are not happy with this state of affairs. To them, the very word "pundit," tucked between "pun" (from the British pound, "to mistreat") and "punk" ("a person of no worth or importance"), has come to sound geeky, a four-eyed nerd who wandered into the wrong end of the dictionary. With its abrupt, hobbled cadence, its suggestion of sound and fury signifying nothing, "pundit" has become one of those labels nobody likes, least of all, it turns out, Dartmouth's own crop of learned opinion-givers.

"It's pejorative," says Linda Fowler, political scholar and director of Dartmouth's Rockefeller Center.

"It sounds like some disease," says David Shribman '76, Pulitzer Prizewinning Washington bureau chief for The Boston Globe. "It's become almost an expletive," says Paul Gigot '77, Wall StreetJournal columnist. "Like lawyer. Or congressman."

"I'm condemned by it," says Morton Kondracke '60, columnist and McLaughlin Group regular. "But I accept it. It's not a particularly popular word, but there deserves to be a name for what we do."

What the pundit does, of course, is often another matter of debate. The pundit is neither guru nor sage, dispensing neither wisdom nor arcana. Nor is the pundit a teacher or politician, who educates or influences events. The Hindu origin, pandit, or "learned man," no longer covers the contemporary pundit, whose head is more likely pointed toward a camera than burrowed in a book.

So what is the pundit? "There's a great deal of knowledge out there," says Dinesh D'Souza '81, of the conservative American En- terprise Institute. "The role of the pundit is to forage academic pastures and tell you what that means." In other words, the pundit tends to think for the rest of us, tells the world what to think, and then endures what the rest of the world thinks of him or her. The pundit, in short, needs a brain as well as opinion, which separates the pundit from the average barstool blowhard, or from, say, Rush Limbaugh. Moreover, the pundit needs marketing as well as brains, which also separates the pundit from, say, that great political science professor. Personality doesn't hurt for pundit-producing, and neither does a general comeliness.

The gate to punditry, however, truly admits few. Particularly at Dartmouth, most pundits begin as intellectual innocents, as scholars or journalists content to study or cite the wisdom of others. Only in time do they reveal the full set of pundit traits, most of which, frankly, the average journalist/scholar can only drone about. To wit:

Epiphanies D'Souza, provocative author on race and education, says he started at Dartmouth as a studious "non-rebel"—until he met friends at The Dartmouth Review. "I was introduced to some very bold and interesting questions that I hadn't thought about," he says. Likewise, Gigot, who weekly debates liberal Mark Shields on News Hour with Jim Lehrer, was a "Catholic, idealistic liberal"—until a constitutional law class with government professor Vincent Starzinger. "Starzinger dissected liberal thought in such a way that you could never quite look at it again in the same way," he says. "He taught me how to think."

Reformed thinkers are often like reformed smokers: They tend to preach the gospel of conversion. They become, in short, pundits.

Point of view True pundits do not equivocate, even in their prepundit lives. Kondracke was once refused a journalism fellowship due to his "advocacy" reporting on Nixon at the ChicagoSun Times. D'Souza's biography of Jerry Falwell, written as an undergrad, leaned straight to the right and explained, for instance, that H.L. Mencken was a "newspaper comedian." Gigot, as a reporter in the Far East, was offered an Op-Ed slot based on a number of pieces he'd written about former president of the Philippines Ferdinand Marcos. To Gigot, most journalists are already pundit wannabes. "It's a great conceit that reporters think they don't carry any ideological baggage or values," he says. "If I had known what I could have gotten away with as a reporter, I would not have become a columnist."

Voyeurism Some pundits, granted, are frustrated politicians, with a burrowed agenda of changing the course of events. More often, though, pundits prefer to watch. "I think most journalists become journalists because they don't want to be responsible for putting warships into the ocean and raising taxes," says Kondracke. "They want to be kibbitzers but they don't want to play." Notes Gigot, "The way modern politics is practiced, you have to mute your points of view. And I think maybe we enjoy the soapbox more."

Media comfort Point a camera at the average Thinking Person, and you'll likely endure obfuscation and lectures. Pundits don't do this. Universally, they possess full-bore confidence and ability to "match noun to verb" (as Gigot puts it). Hence, they find an audience.

Fowler, for instance, found herself a pundit during the New Hampshire primaries ("much to my chagrin") because she was one of the few academians who could interpret the roller-coaster race to bedeviled reporters. Judson Hale '55, editor of Yankee, turned weather pundit because the true weather prognosticator behind The Old Farmer's Almanac has no media affinity. "Dr. Richard Head is a solar scientist," says Hale. "He's not going to joke about his work."

(And if one can believe Vanity Fair, television analyst Laura Ingraham '55 rose to prominence partly because of her ability to photograph well in a leopardprint skirt.)

Nerve Pundits are not fools, but they can risk being thought of that way. "You have to be shameless," says Regina Barreca '79, talk-show regular and feminist scholar. "You can't be worried about what other people are going to say, and you have to make sure you believe what you say because at some point you have to defend it."

Networking Pundits tend to know other pundits, and they particularly tend to know other folks in media. Ingraham reportedly is a D.C. party fixture. Shribman can see Gigot's office from his own in Washington. Kondracke did a radio show that led him to his McLaughlin gig. "One has to spend an awful lot of time networking and keeping one's ear to the ground," says Fowler.

More networking Pundits do not exist on opinion alone. As in journalism, most time is spent nurturing sources, performing research, laying a foundation of facts. Susan Dentzer '77, who, like Shribman, is a Dartmouth Trustee, spent 15 years as a reporter before venturing into analysis. "At an earlier stage, I didn't know enough to know what to think," she says.

"I don't wing it," says Kondracke. "I make lots of phone calls. I talk to lots of people." Adds Gigot, "If all I offered was opinion, I'd long ago have been out of the business.

Deflector shields Those who issue public opinion must endure public opinion. While this can take a harsh form in print (D'Souza, for instance, has been called everything from "controversialist" to "bigot"), man-in-the-street confrontations are also not unknown. ("It's remarkable how potent a few unintelligible mutterings on TV can be," says Shribman.) As a result, most pundits tend to truck with their own kind. Says Fowler, who steers clear of cocktail parties, "When your field is Congress, everyone has an opinion, and they're all unfavorable."

The path of punditry is generally one-way. Having become an established authority, few pundits can change their jobs, or even change their minds. Which fortunately seems to be fine with pundits, all of whom arrived at their task already steeped in a point of view. "One of the frustrations I had as a reporter," says Gigot, "is that you could say so-and-so says this and that, even when you knew they were fools or were wrong. As a columnist, I have the ability to inform based on what I think is a coherent set of principles."

Or as Kondracke puts it, "Better to be an honest pundit than to be a sneaky reporter."

"I try to be genial in person, and I always hear them out." —Dinesh D'Souza

"I always said politics is war by other means." Morton Kondracke

"People think there's a little box in Washington with their name on it, and when they retire, they'll draw money out of that box." Susan Dentzer

"People ask me, 'Why are Yankees so unfriendly?' I tell them it's none of their business." Jud Hale

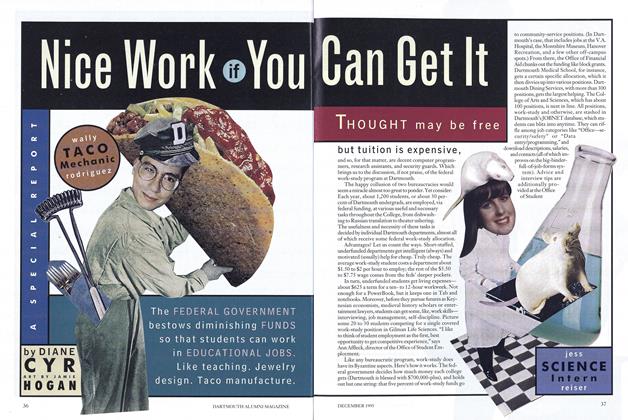

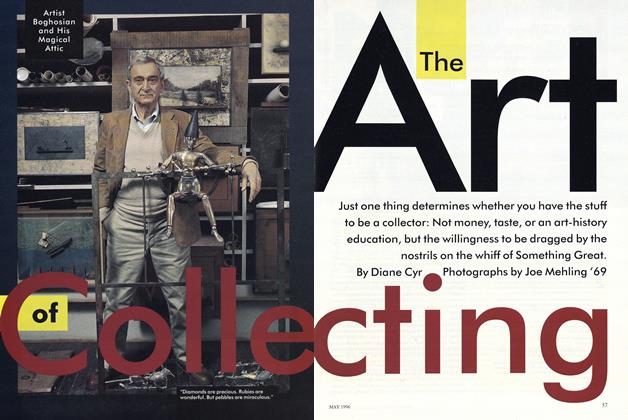

DIANE CYTR. wrote about collecting art in our May '96 issue.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

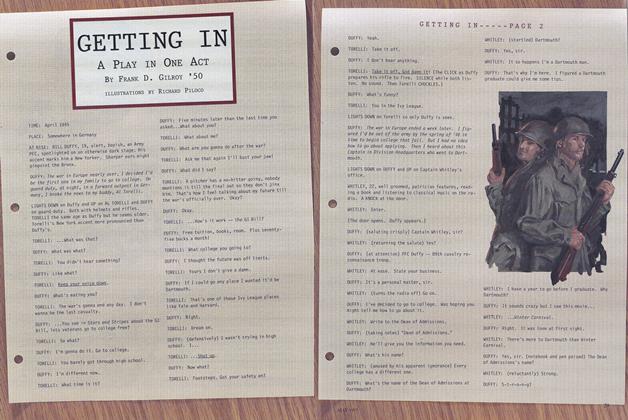

Cover StoryGETTING IN

May 1997 By FRANK D. GILROY '50 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Balance

May 1997 By James Wright -

Article

ArticleHey! Didn't I See You on TV?

May 1997 -

Article

ArticleCold Calculations

May 1997 By Christopher Kenneally 81 -

Article

ArticleBuildings Spring Up and Athletes Get Down

May 1997 By "E. Wheelock" -

Class Notes

Class Notes1979

May 1997 By Jeffrey Boylan, Jim "Wazoo" Wasz

DIANE CYR

Features

-

Feature

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY

JUNE 1967 -

Feature

FeatureMorton, Kilmarx Elected Charter Trustees

MAY 1972 -

Cover Story

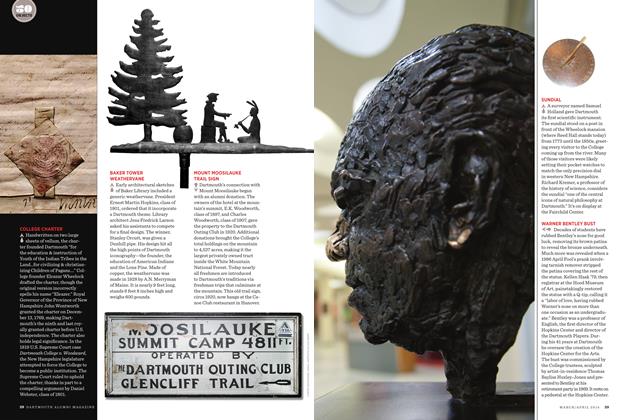

Cover StoryWARNER BENTLEY BUST

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

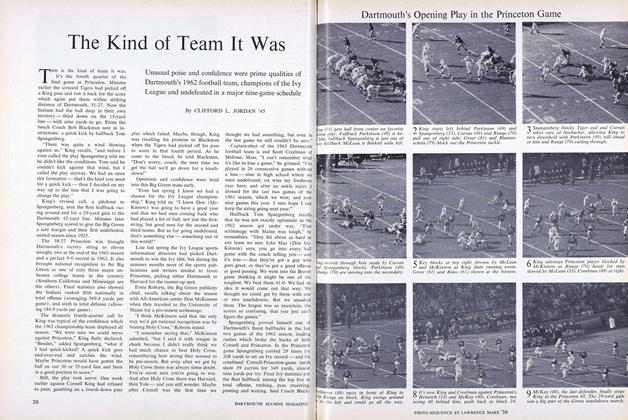

FeatureThe Kind of Team It Was

JANUARY 1963 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeatureWhy in The World: Adventures in Geograhy

June 1992 By George J. Demko with Jerome Agel and Eugene Boe -

Feature

FeatureEnd of a Golden era

APRIL 1982 By Shelby Grantham