AT the library, over lunch, between classes, in formal meetings, the Dartmouth faculty confer compulsively about one issue. Pynchon's latest novel? Foucault's history of sexuality? Rene Thorn's catastrophe theory? Alas, no. It's tenure. The amount of faculty energy spent annually on this one issue is alarming. That energy, re-directed, could generate a halfdozen new courses at Dartmouth. Nationally, the faculty-hours wasted worrying about tenure could run a medium-size university for a year.

The terrible irony is that college professors are trapped in a system of their own devising. That system once worked well. It's been an adequate safeguard of academic freedom, protecting tenured professors from "employers" who disapproved of their political views. Until recently, it has also managed in a fairly humane way to maintain standards of professional excellence. Good graduate students were readily admitted into the teaching ranks; if they performed well, they were eventually given tenure. Denied tenure, they moved to a school of slightly less stringent criteria, gained tenure, and continued to teach until retirement. That was back when universities were expanding, budgets were fat, and teaching positions were aplenty.

All that has changed. Things are now lean in the groves of academe, and the first to feel the pinch are the graduate students. Because only their very very best students now find tenure-track positions, graduate schools are in a well-nigh immoral position. Yet they continue to accept (hire) promising students (cheap teachers of undergraduate courses) on terminal contracts (scant chance of a job at the end of the line). Can you imagine a medical school or law school faculty telling half its class on graduation day to try another line of work? Even more wasteful of years of professional preparation is what happens to the very very best — now junior faculty members — when they come up for tenure. Because of the system's well-ordered design, about half will be denied tenure. Then, because of the economic pressures on university budgets, most of these highly trained "rejects" will not be hired anywhere else and so will leave the teaching profession altogether. As far as I know, no other profession is so wasteful of its own talent, telling many of its best apprentices as they achieve master craftsmanship to try another craft. No other modern profession engages in such a weird, self-lacerating, mid-life purgation. The official myth justifying this firing-andhiring ritual is that it is a way of improving the faculty body, of bringing in "new blood." But only a body given to extreme self-violation would need so many transfusions yearly.

What has Dartmouth done to "minimize this waste and injustice? A reasonable amount. Unlike most of its sister universities, Dartmouth's standard policy is to promote from within rather than make lateral senior appointments from outside. Equally important, Dartmouth conscientiously evaluates its tenure candidates both as teachers and as scholars. Student critiques, class visitations, numerous written assessments by outside scholars, lengthy deliberations by senior department members, by deans, by the Committee Advisory to the President the evaluation process is exhaustingly thorough. The ageold criticisms are still perfectly valid: Tenure judgments can only be as wise as those empowered to make them; some degree of cloning seems inevitable. But, given the system, Dartmouth tries to be as fair as possible. So, why complain?

Well, it doesn't take much to imagine the effects of an all-or-nothing decision hanging for years over one's head. Although the difference between Professor X given tenure and Professor Y denied tenure is usually minimal, that moot discrimination determines one's entire career. It's like granting a lifetime Reynolds Scholarship to an A student while expelling an A-minus student for less-than-acceptable work. Because assistant professors easily convince themselves that just one more hour's research may make the difference, they tend to get monomaniacal about their work. And because they are deeply committed teachers, they end up working 60, 70, 80 hours a week. The effects of these extreme pressures are obviously not all bad, but there is a point of diminishing returns when those virtues valued by the liberal arts are sacrificed for sheer survival. Try asking assistant professors about their sense of self, the stability of their personal relationships, the time they find to nurture their deepest scholarly convictions. Well, better not.

And what about the academic freedom our tenure system is meant to protect? Knowing that senior colleagues must find some reason for rejection, is it likely that junior faculty will cultivate radical ideas? Even if encouraged, will they choose to rock the boat? A depressing number of times I've heard junior professors admit they kept quiet, chose to be politic. After holding their counsel for several years, they may eventually explode, or they may become moral trimmers forever. Either way, our present tenure system for half the faculty seems to discourage rather than enhance freedom of speech.

But the worst effect of our tenure system is the way it subtly poisons a faculty's sense of itself as a community of disinterested, mutually supportive scholars. Relation- ships between senior and junior people can be sorely tested by the necessity of constant scrutiny. Although deep friendships abide, among the junior ranks it requires unusual selflessness to rejoice fully in another's successes. As the big year looms large, the scent of the slaughterhouse can zombify the most stable characters. Side-long glances, a triage ethos, a fierce gallows humor dominate. When the big decision is finally handed down, the sheep (saved) and the goats (damned) are both numbed by their years of purgatorial waiting. When I got tenure I found my feelings a mixture of dumb nothingness and some mutation of Aristotle's catharsis. There was relief, horror, pity but no sense of triumphant joy. I now think I understand why. I had been rewarded by a system that was unjust, not perhaps in its individual decisions made according to the "rules" but in its total effect. As now devised, the tenure process is inevitably and tragically wasteful, leaving in its wake unconscionable suffering, a vitiation of self-respect, a corrosion of human resources.

In 1972, a Dartmouth Committee on Tenure noted "an alarming degree of alienation among younger faculty." That alienation and its poisonous effects on the Dartmouth community can only have increased over the succeeding years. If the alienation of younger faculty is not readily visible, it is because they love their work and refuse to bleat their woes to the world. But I daresay most in the junior ranks, as well as some in the senior ranks, feel the need for a thorough exploration of the humane alternatives to our present tenure system. Among the myriad options, it is possible that no truly humane alternatives exist. It is possible that we who teach at Dartmouth are entrapped entirely by historical changes beyond our control. However, it is also possible that we, the Dartmouth faculty, have greater freedom of choice than we imagine. Reputed to be men and women of moral refinement and creative intelligence, we may be capable of fashioning a more benign mode of self-governance. We may even be capable of designing an exemplary system, one which could be emulated by other colleges. Of one thing I am certain: We are capable of doing nothing. But to do nothing is itself an action one of tacit approval. It is a gesture which says that the present firing-and-hiring system is morally defensible and academically just. I do not find it to be so.

Peter Travis, a specialist in medievalliterature, joined the English Departmentin 1971. He was awarded tenure lastspring.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTenure: an academic necessity

April 1981 By A. E. DeMaggio -

Feature

FeatureQuestion: Who are the Arts for and, Indeed, Who Owns Dartmouth?

April 1981 By Peter Smith -

Cover Story

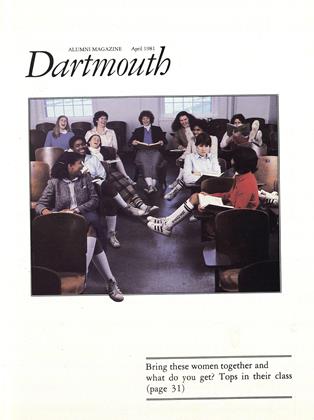

Cover StoryTops in Their Class

April 1981 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryChargé d'Affaires

April 1981 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryBeethoventorte

April 1981 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryGoing Places

April 1981

Features

-

Feature

Feature75 Years of Helping Students

APRIL 1971 -

Feature

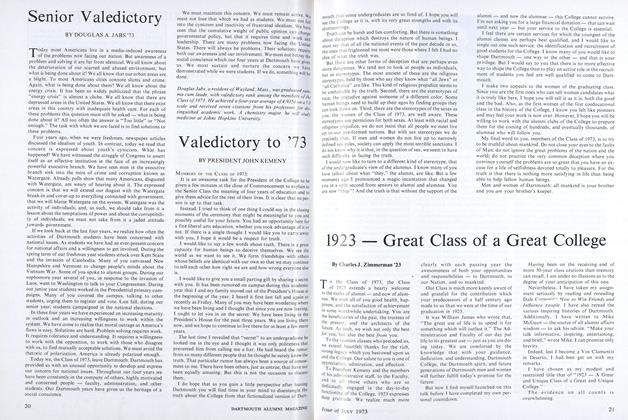

Feature1923 – Great Class of a Great College

JULY 1973 By Charles J. Zimmerman '23 -

Feature

FeatureEat Here

February 1992 By CHRIS WALKER '92 and TIG TILLINGHAST '93 -

Feature

FeatureOUR PASSIONATE PREFERENCE

FEBRUARY 1991 By Joseph D. Mathewson '55 -

Feature

FeatureThe View from Oxford

NOVEMBER 1971 By Sanford B. Ferguson '70 -

Feature

FeatureUNDERPROMISE AND OVERDELIVER

OCTOBER 1990 By William H. Davidow '57