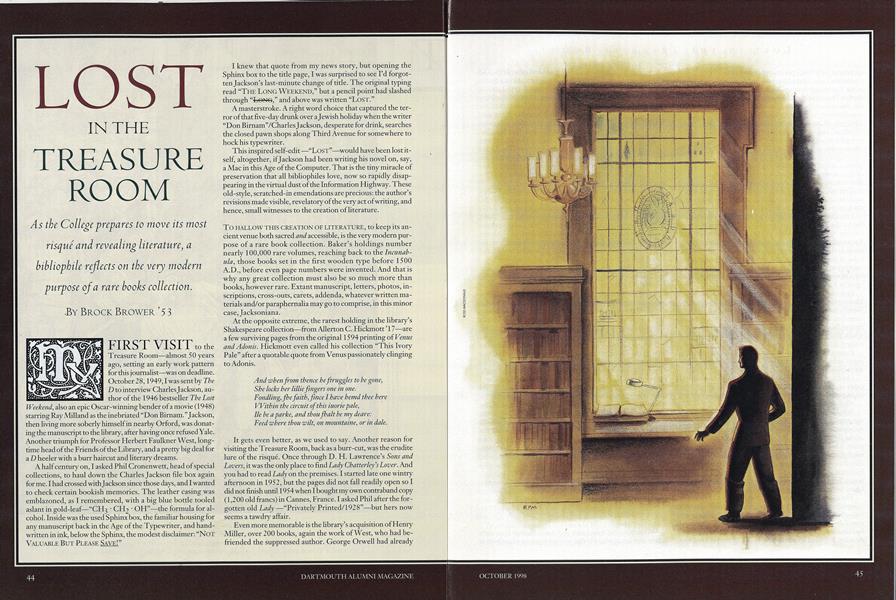

As the College prepares to move its most risque and revealing literature, a bibliophile reflects on the very modern purpose of a rare books collection.

FIRST VISIT to the Treasure Room—almost 50 years ago, setting an early work pattern for this journalist—was on deadline. October 28,1949,I was D to interview Charles Jackson, author of the 1946 bestseller The LostWeekend, also an epic Oscar-winning bender of a movie (1948) starring Ray Milland as the inebriated "Don Birnam." Jackson, then living more soberly himself in nearby Orford, was donating the manuscript to the library, after having once refused Yale. Another triumph for Professor Herbert Faulkner West, longtime head of the Friends of the Library, and a pretty big deal for a D heeler with a burr haircut and literarv dreams.

A half century on, I asked Phil Cronenwett, head of special collections, to haul down the Charles Jackson file box again for me. I had crossed with jackson since those days, and I wanted to check certain bookish memories. The leather casing was emblazoned, as I remembered, with a big blue bottle tooled aslant in gold-leaf-"CH3 CH2 OH"-the formula for alcohol. Inside was the used Sphinx box, the familiar housing for any manuscript back in the Age of the Typewriter, and hand written in ink, below the Sphinx, the modest disclaimer: "NOT VALUABLE BUT PLEASE SAVE!"

I knew that quote from my news story, but opening the Sphinx box to the title page, I was surprised to see I'd forgotten Jackson's last-minute change of title. The original typing read "THE LONG WEEKEND," but a pencil point had slashed through "LONG," and above was written "LOST."

A masterstroke. A right word choice that captured the terror of that five-day drunk over a Jewish holiday when the writer "Don Birnam"/Charles Jackson, desperate for drink, searches the closed pawn shops along Third Avenue for somewhere to hock his typewriter.

This inspired self-edit —"LOST"—would have been lost it self, altogether, if Jackson had been writing his novel on, say, a Mac in this Age of the Computer. That is the tiny miracle of preservation that all bibliophiles love, now so rapidly disappearing in the virtual dust of the Information Highway. These old-style, scratched-in emendations are precious: the author's revisions made visible, revelatory of the very act of writing, and hence, small witnesses to the creation of literature.

To HALLOW THIS CREATION OF LITERATURE, to keep its ancient venue both sacred and accessible, is the very modern purpose of a rare book collection. Baker's holdings number nearly 100,000 rare volumes, reaching back to the Incunabula, those books set in the first wooden type before 1500 A.D., before even page numbers were invented. And that is why any great collection must also be so much more than books, however rare. Extant manuscript, letters, photos, inscriptions, cross-outs, carets, addenda, whatever written materials and/or paraphernalia may go to comprise, in this minor case, Jacksoniana.

At the opposite extreme, the rarest holding in the library's Shakespeare collection—from Allerton C. Hickmott' 17—are a few surviving pages from the original 1594 printing of Venusand Adonis. Hickmott even called his collection "This Ivory Pale" after a quotable quote from Venus passionately clinging to Adonis.

And when from thence he truggles to be gone,She locks her lillie fingers one in one.Fondling, fhe faith, fince I have hemd thee hereWithin the circuit of this iuorie pale,lie be a parke, and thou fhalt be my deare:Feed where thou wilt, on mountaine, or in dale.

It gets even better, as we used to say. Another reason for visiting the Treasure Room, back as a burr-cut, was the erudite lure of the risque. Once through D. H. Lawrence's Sons andLovers, it was the only place to find Lady Chatterley's Lover. And you had to read Lady on the premises. I started late one wintry afternoon in 1952, but the pages did not fall readily open so I did not finish until 1954 when I bought my own contraband copy (1,200 old francs) in Cannes, France. I asked Phil after the forgotten old Lady —"Privately Printed/1928"—but hers now seems a tawdry affair.

Even more memorable is the library's acquisition of Henry Miller, over 200 books, again the work of West, who had be friended the suppressed author. George Orwell had already spoken out for Miller's genius, and a senior honors student ha d published his thesis on Miller in the Dartmouth Literary Magazine. But the two Tropics could still be read only under those leaded windows, mullioned with Dartmouth history. I asked Phil for The Tropic of Cancer, published in 1934 by "MEDVSA" and inscribed to West with a wry gibe at society's censure—from hiscancerous friend Henry Miller 11/12/44.

I DWELL ON THE FORBIDDEN—and the silly bent of those times—because such access bespeaks the freedom that the library has always accorded Dartmouth students. And alumni. The library extends free lifetime privileges to anyone who attends the College, and these reach beyond its open stacks to its literary treasures, available literally upon request.

I decided to test this out, as an investigative greybeard, before the library shifts its special collections to the Rauner Library in renovated Webster Hall. I visited the Treasure Room off and on over three College terms marked by a seasonal turn of those huge pages in Daniel Webster's elephant folio of Audubon prints. We went from hummingbirds in summer to the wild turkey in late fall to the Falco Washingtonii as winter set in. I trust this indoor bird watch will continue at Rauner.

I asked first for the First Folio_the earliest round-up of Shakespeare's plays in 1623, compiled by two of his actors, John Heminges and Richard Condell. They wanted to make his tragedies, comedies, and histories available "To the great Variety of Readers." Their book is the singular literary miracle by which Shakespeare's playscripts survived, and a First Folio is easily worth a million dollars.

Passing by my table, where I had the Folio's lightly speckled pages open to The Tempest, Phil said quietly, "I hope you've washed your hands."

I had, and was immersed in Prospero's magic and the palpable excitement that is conjured up by the Folio's line-by-line impact. Also, grateful for what is mercifully missing. No footnotes.

Who among us can remember reading Shakespeare without stumbling through footnotes? But the Folio, obviously, has no apparatus. The scholars come later. The endorphin high of the Folio comes from the very nakedness of these scripts in print. Their double columns render Shakespeare's scenes at the right length, somehow proportional to the elapsed time they should occupy on stage. Paradoxically, the reader gains an historical sense of striking immediacy —the next best thing to seeing The Tempest at the Globe. The characters are right there. I have never read a better Prospero.

The only other script I requested was the Final Continuity for Winter Carnival, Property of Walter Wanger [15] Productions, Inc.—that worst-of-1939 film starring Ann Sheridan. It is among over 2,200 film scripts held by the library. I always believed it had been written by Budd Schulberg '36 with scant help from a drunken F. Scott Fitzgerald (cf.Schulberg's novel The Disen chabted) But I find Budd had other help. The credits on the scruffy script read BUDD SCHULBERG/MAURICE RAPF/LESTER COLE.Rapf, a class ahead of Schulberg and later a professor of film at the College, did the rewrite, and Cole the polish. The ultimate absurdity is that this snowy Hollywood confection was concocted by three leading Thirties Leftists, including one of the Hollywood Ten (Cole). I What it was really all about, Rapf now tells me, was "getting Wanger an honorary degree from Dartmouth." Instead of overthrowing capitalism, they were helping garner its honors.

More randomly, I asked after my favorite novelists. I won't list all the first editions I happily dipped into, except my favorite Charles Dickens—Little Dorrit.The library's two-volume "first" has the famous Phiz illustrations, with Little Dorrit on the frontispiece, bravely exiting the Marshalsea prison, round-eyed as a petite Munch Scream. But this is uniquely the Dorrit that Thomas Carlyle gave his marvelous wife, Jane, inscribed: first pencil-stroke/ 6 Nov r 1862/Quod faustum sit! and signed T C. I agree with his Latin, "May this find favor!"

Lastly, I decided to pickup on the poets whose singing—and very voices—have spoken to me most resonantly over the decades. The library's greatest such treasure is its Robert Frost 1896 collection. Not a word can be written about Frost without consulting Frost's notebooks, and Jay Parini is only the latest biographer to study them in the Robert Frost Room. But I chose two other modern poets, well represented in the Treasure Room, in both cases involving some entanglement, on my part, with their donors.

William Carlos Williams, who inspired the generation of New Poets, is a far greater poet than his epigoni. He forged a concrete imagery out of America's cityscapes, out of a doctor's compassion (his day job) for the urban poor in the ethnic melting pot. Sadly, that put him forever beyond his admirer David Raphael Wang '55, a sometime poet with a more ideological bent. Wang jumped to his death from the Barbizon Plaza Hotel in 1977, but he left to the library some important Williams publications. I looked among them, and found W.C.W.'s first book—Poems by William C. Williams—self-published in 1909 and so fall of errors and embarrassing lines that barely ten copies survive, invaluably, today. But midst all his Tenny sonian twaddle, I find this one important chorus in "A Street Market/N.Y. 1908."

Eyes that can see,Oh, what a rarity!For many a year gone byI've looked and nothing seenBut ever beenBlind to a patent wide reality.

Williams would soon cease and desist forever from such cutesy metrics, but here is that printed moment when he first opened his eyes to "a patent wide reality," of which he built lyrics as sturdy as wheel barrows and metaphors like power plants.

Finally I indulged my deep delight in Robert Burns. Easy enough to do among 1,500 books and pamphlets in the Burns Collection, to which the Friends keep adding. Their capstone purchase in 1957 brought the library a few precious pages from the 1786 Kilmarnock edition of his Poems, Chiefly in tScottish Dialect. Phil set the brittle pages before me, and I admit I hesitated. Turning them over was like leafing through old butterfly wings. But it was worth it. I got to read through "The Holy Fair," one of the great social satires, Burns's long take on a Sunday religious revival. All the while with his soft brown eye on the bonnie lasses, tracking the steady rise that faith and "ither" simulants are giving the Flesh. By nightfall

Chiefly in the Scottish dialect, Houghmagandie is "fornication." Literally, the "dancing"—gandie—of "thighs"—hough —as in hox, hocks. We are back again in bawdry.

Which brings me round again to that Charles Jackson file. Jackson lived several more years in Orford, but the writing was not going well. His second novel, The Fall of Valor, about homosexuality, had been another scandal but not a success. Then over the AP wire at The D came an item on his arrest near Orford for drunken driving. Departure and divorce followed. Jackson recovered (though never his talent).

We met again in the mid-sixties at Breadloaf, both teaching at the writers conference. He was a much subdued man, less dapper, softened rather than hardened by his own troubles. Still, he had an enormous enthusiasm for really good writing, as if determined to admire and promote what he knew he would never achieve.

The last time I saw him, shortly before he died, was under the flood wash glare of a Broadway marquee at intermission, where the buzz was over that evening's mad elegiacs for the dead Lenny Bruce. Jackson had gone beyond soft to fat, with the shine of the fey upon him, but he reached out to shake my hand and congratulate me on a short story I'd just published in Esquire. He spoke critically, but with honest praise, against the hyped sibilance around us. He was a strangely sincere presence—buried in him the drunk, the flaneur, even the deviantbut I knew he meant every word he said. And it moves me to this day.

Among the papers in the Jackson file, I found a long story of his own. Still in manuscript, forwarded to the library by an Orford friend, unpublished, entitled "The Sunnier Side." Almost a novella, it is an early attempt at what would now be called confessional writing. His hero/narrator is "Charles Jackson," and his narrative is a 20,000-word letter in reply to another letter received from a childhood acquaintance, "Miss Brenner," who objects to how Jackson has treated three real women they both knew in a recent short story he had published in Good Housekeeping. But the stories of their true fates, Jackson reveals in his letter, encompass far greater horrors—alcoholism, sexual abuse, homicide—hidden under their hometown's protective veneer of Victorian optimism.

He writes passionately of his need to tell these stories. It is story alone that "can reveal the most secret places of life," he quotes from none other than D. H. Lawrence, "for it is in the passional secret places of life, above all, that the tide of sensitive awareness needs to ebb and flow, cleansing and freshening."

Jackson was already mixing memoir and fiction as early as the late fifties, in a crude fashion that has since been refined into a new art form. That odd man is here "outing" himself, trying to step from behind "Don Birnam" to become "Charles Jackson," as so many of his readers long suspected. But is he really? Charles Jackson, the writer, can be utterly believable in his story-telling at the very same time that his character "Charles Jackson" is so arch, so conspicuously self-referential, just too damn li'try to be believed at all. But I must admit that at least once, "Charles Jackson" caught me out completely.

"One last word, then I am done with the subject-matter of subject-matter," he tweaks Miss Brenner. "I'm sure you will be interested to know that the beautiful passage I quoted earlier from D. H. Lawrence was culled from that most immoral and disgusting book, Lady Chatterley's over."

The odd Jackson trove will soon move over to Rauner, along with the rest of the library's treasures. Everything will remain accessible, Phil assures me, only more safely preserved. That fits with another journalistic memory I harbor, from a later time, when I sat up in the Webster Hall balcony, listening to the firebrand Stokely Carmichael extoll black power. Carmichael was uncharacteristically subdued that evening, quoting long, dull passages from a written text, until he was challenged by a drawling, mock-bored Southern voice near me in the balcony.

"Now that we know you can read...." Instantly, Carmichael caught fire. "It wasn't that long ago that folks like you wanted to keep me from reading!" I can still hear the outburst of laughter and applause that might well echo memorially around those refurbished Webster walls, as Rauner makes all readers welcome.

BROCK BROWER is the author of two novels, including The Late Great Creature. His stories and articles have appeared in Esquire, Harper's, The New Yorker, and other magazines. Baker's Special Collections mill shut down on September 30 and reopen December 1in the new Rauner Library.

There's some are fou o' love divine;There's some are fou o' brandy;An' monie jobs that day begin,May end in HoughmagandieSome ither day.

"Phil set the brittle pages before me, and I admit I hesitated. Turning them over was like leafing through old butterfly wings."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

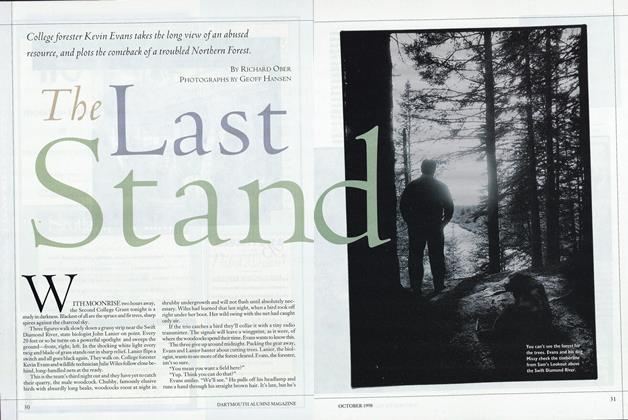

Cover StoryThe Last Stand

October 1998 By Richard Ober -

Feature

FeatureNomss de Blitz

October 1998 By NOEL PERRIN -

Feature

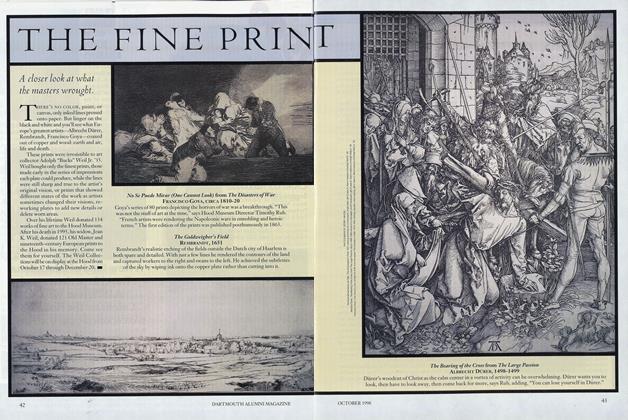

FeatureTHE FINE PRINT

October 1998 -

Article

ArticleA Thankless Job (Because You Didn't Know Who to Thank)

October 1998 -

Article

ArticleWhen a Kid Goes Green, Getting In Is Only the Beginning

October 1998 By Mom -

Class Notes

Class Notes1986

October 1998 By Davida (Sherman)

Features

-

Feature

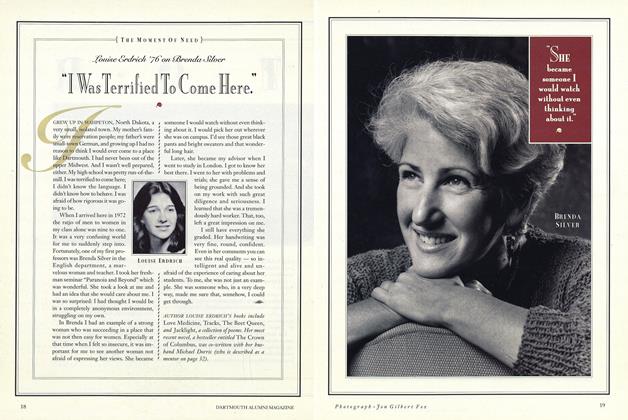

FeatureLouise Erdrich '76 on Brenda Silver

NOVEMBER 1991 By Brenda Silver -

Feature

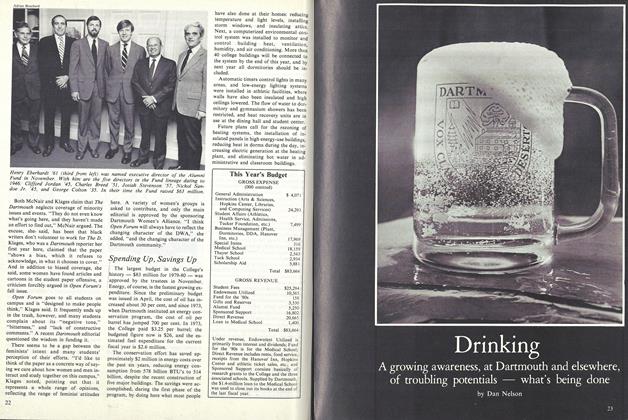

FeatureDrinking

JAN./FEB. 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureMinimum Standards

APRIL • 1985 By Gayle Gilman '85 -

Feature

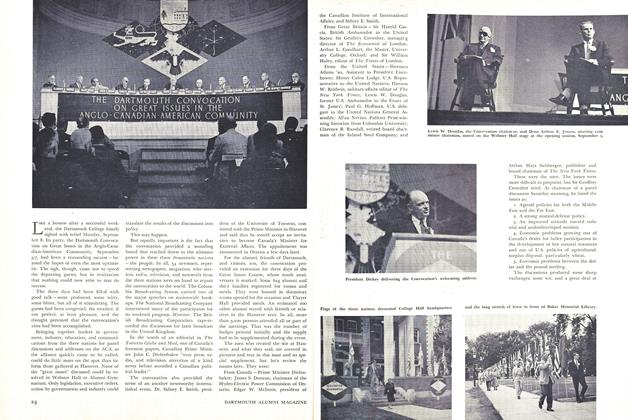

FeatureTHE DARTMOUTH CONVOCATION ON GREAT ISSUES IN THE . ANGLO – CANADIAN – AMERICAN COMMUNITY

October 1951 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureThe First 25 Years of the Dartmouth Bequest and Estate planning Program

September 1975 By Robert L. Kaiser '39 and Frank A. Logan '52 -

Feature

FeatureThe Disappearing Ivory Tower

DECEMBER 1963 By SAMUEL B. GOULD