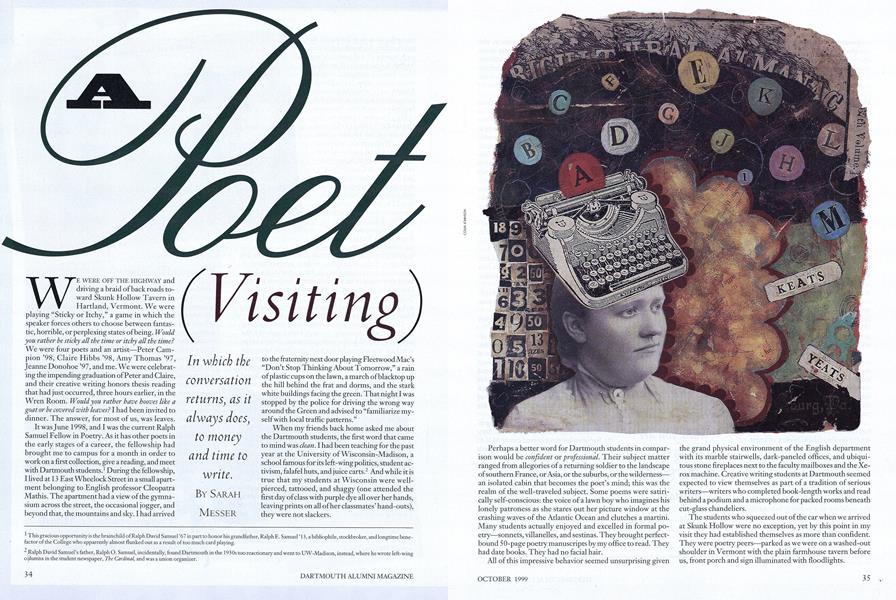

WE WERE OFF THE HIGHWAY and driving a braid of back roads toward Skunk Hollow Tavern in Hartland, Vermont. We were playing "Sticky or Itchy," a game in which the speaker forces others to choose between fantastic, horrible, or perplexing states of being. Wouldyou rather be sticky all the time or itchy all the time? We were four poets and an artist—Peter Cam- pion '9B, Claire Hibbs '9B, Amy Thomas '97, Jeanne Donohoe '97, and me. We were celebrat- ing the impending graduation of Peter and Claire, and their creative writing honors thesis reading that had just occurred, three hours earlier, in the Wren Room. Would you rather have hooves like agoat or be covered with leaves? I had been invited to dinner. The answer, for most of us, was leaves.

It was June 1998, and I was the current Ralph Samuel Fellow in Poetry. As it has other poets in the early stages of a career, the fellowship had brought me to campus for a month in order to work on a first collection, give a reading, and meet with Dartmouth students.1 During the fellowship, I lived at 13 East Wheelock Street in a small apartment belonging to English professor Cleopatra Mathis. The apartment had a view of the gymnasium across the street, the occasional jogger, and beyond that, the mountains and sky. I had arrived to the fraternity next door playing Fleetwood Mac's "Don't Stop Thinking About Tomorrow," a rain of plastic cups on the lawn, a march of blacktop up the hill behind the frat and dorms, and the stark white buildings facing the green. That night I was stopped by the police for driving the wrong way around the Green and advised to "familiarize my- self with local traffic patterns."

When my friends back home asked me about the Dartmouth students, the first word that came to mind was clean. I had been teaching for the past year at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, a school famous for its left-wing politics, student activism, falafel huts, and juice carts.2 And while it is true that my students at Wisconsin were wellpierced, tattooed, and shaggy (one attended the first day of class with purple dye all over her hands, leaving prints on all of her classmates' hand-outs), they were not slackers.

Perhaps a better word for Dartmouth students in comparison would be confident or professional. Their subject matter ranged from allegories of a returning soldier to the landscape of southern France, or Asia, or the suburbs, or the wilderness-

an isolated cabin that becomes the poet's mind; this was the realm of the well-traveled subject, Some poems were satirically self-conscious: the voice of a lawn boy who imagines his lonely patroness as she stares out her picture window at the crashing waves of the Atlantic Ocean and clutches a martini. Many students actually enjoyed and excelled in formal poetry—sonnets, villanelles, and sestinas. They brought perfectbound 50-page poetry manuscripts by my office to read. They had date books. They had no facial hair.

All of this impressive behavior seemed unsurprising given the grand physical environment of the English department with its marble stairwells, dark-paneled offices, and übiquitous stone fireplaces next to the faculty mailboxes and the Xerox machine. Creative writing students at Dartmouth seemed expected to view themselves as part of a tradition of serious writers—writers who completed book-length works and read behind a podium and a microphone for packed rooms beneath cut-glass chandeliers.

The students who squeezed out of the car when we arrived at Skunk Hollow were no exception, yet by this point in my visit they had established themselves as more than confident. They were poetry peers—parked as we were on a washed-out shoulder in Vermont with the plain farmhouse tavern before us, front porch and sign illuminated with floodlights.

If you could only listen to onetype of musk for the rest of yourlife would you choose REOSpeed Wagon or Meatloaf? The question upon entering. Meatloaf, Meatloaf, Meatloaf. Unanimous Meatloaf.

You can learn a lot about people by talking about poetry.3 Who they read and admire says something; who they don't says something else. Do they like new formalists like Dana Gioia? Or language poets like Lynn Hejinnian? What do they think of Richard Howard? By this car trip, I had already had intense discussions about poetry with Peter at cafes, receptions, or the (one) local pub. When poet Robert Polito visited, Claire, Peter, Amy, and English professor Tom Sleigh and I took him over to the pub after his reading to watch the last episode of Seinfeld on a bigscreen TV. During commercials, we dished about the Yale Younger Poets scandal. Do you agree with W.S. Merwin, or don't you—not a single unpublished poet under 40 worthy of an award? We talked about trends and trivialities, pantoumes and ghazals, and the kinds of art some poets keep in their bathrooms.

This interaction with actual poets and poetry business was something that I only dreamed about in college. When I tried to conceptualize a poetry community, I always imagined it happening someplace far away like New York or wherever Allen Ginsberg lived. Not Dartmouth. Not rural New Hampshire or Vermont.

The college I attended, ironically, was just that. As a Middlebury student I attended the Bread Loaf Writer's Conference each summer trying to absorb anything I could about contemporary writers. During the school year, however, I didn't hear much about living writers—who they were, where they lived, how they made money. As a student, how one got from a seat on a folding chair in the audience to a position behind the podium at Bread Loaf was a mystery to me. I looked at the bright slim volumes of poetry in the Bread Loaf bookstore with my finger in my mouth, my eyebrows worming.

The questions at the table were getting more complex. We were half way through dinner and a bottle of wine—salads were pushed aside, bowls of pasta lingered.

Would you rather make$15,000 a year and live ina rural trailer park—buthave to work for the money atIa dead-endjob at a gas stationor McDonald's—or wouldyou rather earn $20 millionhut be tortured every year ofyour life for two and a halfhours by a master torturer?

"Two and a half hours isn't that long. And $20 million can buy a lot of therapy and drugs."

"But for your whole life?" "Have you ever worked at McDonald's? Try being on fries for eight hours."

"Yeah, but it's a ?naster torturer. Like, they know your deepest fears. Ifyou hate snakes, they put you into a vat of snakes up to your neck."

"Can I be married or have a dog?"

"But the torturer doesn't kill you, right? He just tortures you."

"Can I write in the trailer park after work?"

The conversation returned, as it always does, to money and time to write. Twenty million dollars could buy a lot of time to write, but several of us around the table figured that being tortured would not leave emotional space for much of anything creative. Living in a trailer park might. Obviously, none of us sitting around the table were in it for the money.

But all of us were, or were hoping to be, poets—to make a living at it. Amy had already been accepted into an M.F. A. program at B.U. Peter and Claire both talked about applying. But it was clear that part of the excitement of being together and talking about the future was that it is a risky future.

The most frequently asked question I received at Dartmouth was, "How do you do it?" Meaning: be a poet. Meaning also: pursue a craft that is only understood by a very insular group of people and is misunderstood by generally everybody. Meaning: sleeping on futons and keeping books in milk crates way after grad school. Meaning: your friends are buying new cars and buying homes and expensive daycare for their kids while you are wondering if you can afford to buy fancy mustard.

My answer, initially, was this: I went to grad school to get an M.F.A. knowing that I was paying for a degree that didn't guarantee me a job. I painted houses in the summer. I went on unemployment. I went to artist colonies while on unemployment. I did whatever I could to find time to write.

Yet this wasn't the real meaning of their question. They wanted to know how I "did it," meaning: how did I decide? How did I dare decide?

Recently I was asked to return to Middlebury to participate in a panel on "Women in the Arts." The question about daring to be a poet, however, had a different twist—how does a young woman at Middlebury (or Dartmouth) dare to be a poet and not a lawyer? There was some discussion of the Teflon quality of sexism in the arts; not much about the conflicts of motherhood; even less about how to survive practically as an artist. There were very few student faces in the audience. A friend of mine who teaches at an elite New England college complained that even though she has wonderful undergraduate poets, invariably five years after graduation they write to her with recommendation requests for business or law school. The purpose of the symposium was to illustrate that it means something different for a young person to declare him or herself an artist. In his poem, "Perfect Entry," Ralph David Samuel makes the patrilinear handoff look easy:

(He) Declared himself 'a writer as his son to beThe same he prop hesized for me and soOn down his line for those to follow..

If one has a family line of writers (and names) perhaps a gender identity crisis 4 isn't necessary—but my point is that it is difficult for anyone to be a writer, especially a college student. 5 For example, Ralph E. Samuel Jr., writing radical prose for the Wisconsin student newspaper, forgot (or purposefully omitted?) the "Jr." from his name. This angered his father, Ralph E. Samuel Sr.—owner of the'same name and very different political views. Ralph E. Jr. changed his name to "Ralph O." and continued to write despite his father's disapproval. In this lineage of literary Ralphs, Ralph David is quick to point out that he intentionally did not choose which Ralph Samuel the poetry fellowship actually honors.

But Ralph David Samuel did make a choice—to give this money back to Dartmouth students and to young poets. Perhaps he realized that having a good education helps; having teachers who are also poetsCynthia Huntington, Cleopatra Mathis, and Tom Sleigh—helps even more; but having a community of peers, however one finds it, is most important. The purpose of the Ralph Samuel Fellowship is to encourage that community among a younger generation.

Perhaps, in the end, it doesn't matter what one does for a living, or where one lives. What matters is that they love the work, they empathize, and they try. And you can tell poets and lovers of poetry by the way they can't stop talking about books they've read or readings they've heard even if it is almost midnight in the middle of a deserted Vermont road, having left the table and the tavern and walked into the night to stand, as we were, in a shifting group under the circle of the street's only lamp, continually saying what if, caught in endless language games, not wanting to say goodnight.

Poet and writer SARAH MESSER is currently working on Red House, the memoir of a childhood place.

In which theconversationreturns, as italways does,to moneyand time towrite.

The most frequentlyasked question I heardwasj "How do you doit?" Meaning: he apoet. Meaning:yourfriends are buyinghomes and expensiveday care for their kidswhile you arewondering if you canafford to buy fancymustard."

Having a goodeducation helps;having teachers whoare also poets helpseven more; buthaving acommunity of peers,however one findsit, is mostimportant.

1his gracious opportunity is the brainchild of Ralph David Samuel '67 in part to honor his grandfather, Ralph E. Samuel '13 a bibliophile, stockbroker, and longtime benefactor of the College who apparently almost flunked out as a result of too much card playing. 2 Ralph David Samuel's father, Ralph O. Samuel, incidentally, found Dartmouth in the 1930s too reactionary and went to UW-Madison, instead, where he wrote left-wing columns in the student newspaper, The Cardinal, and was a union organizer. 3 Ralph David Samuel is himself a poet. In a letter to me he wrote: "In 1994 at a summer workshop at Bennington, Luci Brock-Broido and Frank Bidart inspired me to join the Church of Poetry, and soon I was confirmed." 4 The gendered poetic stereotypes are: (for women) the crazy white-wearing attic sylph/cruddy-toothed candy-addicted misanthrope; or the black-wearing, intellectually swashbuckling big-hair beatnik type. For men it is the sensitive alcoholic bear-bodied nature-loving shot-gun suicidal or the black-wearing, intellectually swash-buckling (or mopey) big hair beatnik type. None of the people in this article resemble the description above. 5 Now might be a good time to note that Ralph David Samuel is actually a lawyer. He writes poetry when he can, and empathizes with the global problem of finding time to write.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Research Question

October 1999 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

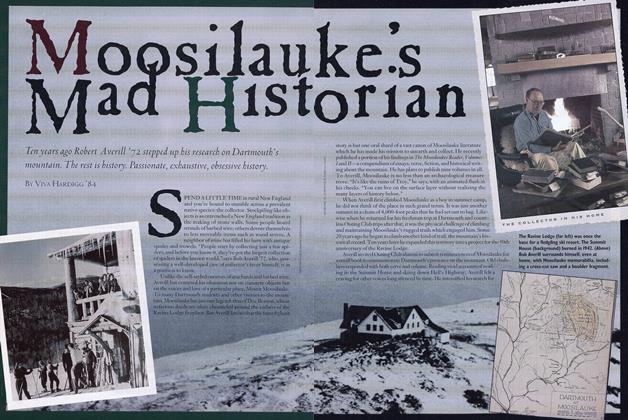

FeatureMoosilauke's Mad Historian

October 1999 By Viva Hardigg '84 -

Article

ArticleStories on Rye

October 1999 By Tamar Schreihman '90 -

Article

ArticleTeamwork

October 1999 By President James Wright -

Article

ArticleArtists 22, Philistines 14

October 1999 By Noel Perrin -

Class Notes

Class Notes1985

October 1999 By Leslie A. Davis Dahl, John MacManus, Shelley L. Nadel

Features

-

Feature

FeatureYORKE BROWN

Sept/Oct 2010 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryFinding God at Dartmouth

May/June 2005 By CATHERINE FAUROT, MALS ’04 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryBack on the Wall (where they belong)

SEPTEMBER 1985 By Georgia Croft -

Feature

FeatureA New Investment Concept: Total Return

JULY 1969 By JOHN F. MECK '33 -

Cover Story

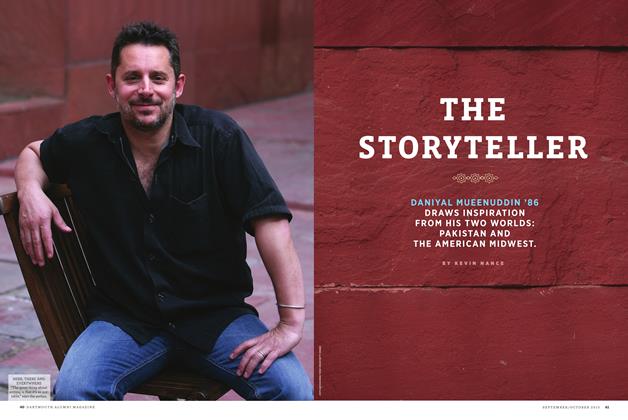

Cover StoryThe Storyteller

September | October 2013 By KEVIN NANCE -

Feature

FeatureAfter Iran: Can We Have a Foreign Policy?

NOVEMBER • 1987 By Stephen Bosworth '61