The fraternities

PROLOGUE: The time is the late sixties, barely a decade after Dartmouth fraternities confronted and mostly overcame the embarrassing anomaly — for a liberal arts institution — of national fraternity charters that discriminated against blacks and Jews. Attention shifts to civil rights, Vietnam, campus unrest, and the fraternities, variously the focus of much that was good and ill at Dartmouth, begin to appear slightly "irrelevant." Membership declines, many alumni lose interest in their former houses now gone local, few house advisers exert much influence, concern for the buildings dwindles, and the administration — from the President and the deans on down — has other, more volatile concerns. It is a time of malign neglect, and the mood is hardly exclusive to Dartmouth. In 1968, after several years of study, the trustees of Williams College abolish fraternities.

ACT I: In the mid-1970s, at about the time that Dartmouth students showed renewed interest in joining fraternities, there was a rising concern both on and off the campus about the condition of the houses and the behavior of some of their members. In 1976, the Trustees appointed a fraternity study committee. In its reports the committee acknowledged that most of the houses were in deplorable physical and financial shape and concluded that a definition of the fraternities' legal and financial relationship to the College was in order. The relationship, the committee said, should be fixed for the first time in a formal fraternity constitution outlining specific privileges and obligations. With the constitution should come strenuous efforts to relieve the fraternities' chaotic financial situation. (See "An Unease on Webster Avenue," April 1978 ALUMNI MAGAZINE.)

Last February, the Trustees approved a ten-page constitution headed by a preamble that began favorably, "Fraternities at Dartmouth are integral members of the College community" and continued more sternly, "and as such must share . . . [the] responsibility for seeing that the fraternity system continues to make a significant positive contribution to the Dartmouth experience of present and future generations. . . ." The constitution promised the College's financial assistance, set forth operating responsibilities (including standards for building maintenance), and es- tablished a board of overseers composed of alumni, faculty, fraternity members, representatives of house corporations, and a Trustee. Their job was to be a sweeping one: to "oversee the operations and activities of the recognized fraternities at Dartmouth" and to mediate between the College and the fraternity system.

From the administration's point of view, the constitution was intended to infuse new life into the system, which appeared in danger of collapse. However, many of the fraternity presidents denounced the constitution as an attempt to abrogate their autonomy. The ensuing debate was acrimonious, with the dean of the College, Ralph Manuel '58, the target for the students' criticism. When the fraternities declined to ratify, Manuel said the alternative was closing the houses. When the fraternities asked town officials about their status without College recognition, they were told that the buildings would be viewed as boarding houses and in violation of zoning codes. After discussing their position with a lawyer, the fraternities grudgingly signed the constitution.

ACT II: Enter James Epperson, a 47- year-old English professor. Epperson, who came to Dartmouth in 1964, hardly fits the image of the faculty Puritan, but he was dismayed by evidence of fraternity involvement in sexual abuse of women, in racial conflicts, in a rising incidence of drunkenness requiring emergency medical treatment, in what he called "antiintellectualism and intolerance of the rights of others." For Epperson, the fraternities' intransigence over the new constitution — which was offered as a life-saving measure — symbolized their refusal to consider reform or even recognize the need for reform. Last spring, Epperson drafted his motion "to abolish fraternities and sororities at Dartmouth College." It was signed by 22 of his colleagues and scheduled for faculty debate in the fall.

At the faculty meeting on November 6, Epperson spoke for 55 minutes, beginning with a reference to Paradise Lost. His manner was calm, his words blunt. The College, he said, stands for civilization — for community, compassion, tolerance, and thoughtfulness. He charged the fraternities with standing in opposition to these ideals, and went on to cite specific examples of behavior inimical to civilization. (See also Epperson's "Vox" essay, "The Future Is Before Us," on page 72 of this issue.) The motion was seconded by Government Professor Charles McLane '41, who identified himself as a fraternity member while an undergraduate at Dartmouth and who recounted the several "mostly failed" attempts to encourage fraternity reform since the 1920s. "Reform is no longer a remedy," McLane said.

In a rare procedure for faculty meetings, students were permitted to comment. They spoke on both sides of the issue, one group condemning the fraternities as racist and sexist, the other — consisting of Inter-fraternity Council representatives — defending the houses and the progress made in recent months. Two members of the faculty distributed prepared statements opposing the Epperson motion. Charles Stinson, professor of religion and a fraternity adviser, attacked the "cliched charge of anti-intellectualism" and said it was unfair to accuse all the fraternities for the behavior of "a small percentage of the membership of certain fraternities." Both Stinson and Government Professor Howard Erdman, also a house adviser, criticized the Epperson motion as offering no positive alternative to fraternities.

Another faculty member, David Lemal, professor of chemistry, offered a substitute motion to table abolition in favor of allowing more time for discussion and reform. It was defeated by a ratio of 3-1. On the Epperson motion the faculty voted 67-16 for abolition. (After the meeting, it was estimated that of the 320 members of the faculty, 240 were available to attend the meeting and about 120 actually were present.)

The faculty vote took everyone by surprise. Most, including Epperson, had predicted the outcome would resemble Lemal's substitute motion. The consensus was that the ill-prepared testimony in defense of fraternities had a significant bearing on the result. The vote, which some viewed as a clear-cut expression of faculty opinion and others as the voice of a majority-of-the-minority, has been sent to the Trustees. They will consider it at their next meeting, in late February.

ACT III: If the immediate campus reaction to the vote was one of astonishment, the fraternities and sororities were quick to mobilize a response. "We need not only to defend ourselves, but we need to change," David Lurie '79 said at an Interfraternity Council meeting held a few hours after the faculty voted. Defense — in the form of letters to alumni and to The Dartmouth — and change — a concerted effort toward selfdiscipline and positive reform — came within the week.

The IFC formed a Special Action Committee headed by a sorority president, Gail Frawley '79, and in a letter to The Dartmouth announced that "we . . . have no intention of exploding into defensive indignation or sitting back to await complacently a Trustee vote of confidence." Instead, the committee said it was going to "examine the alleged shortcomings of the fraternities" and view the faculty vote as a mandate "for a collective effort within the College community to modify and improve" the system. The full IFC urged individual houses to discontinue use of the Indian symbol, scheduled several Collegewide meetings to discuss the issue, and voted to hold fraternity houses accountable for the behavior of individualmembers. Explaining this concept of ultimate responsibility, one fraternity president said that in the past if "a guy in members. Explaining this concept of ultimate responsibility, one fraternity president said that in the past if "a guy in our house went over and trashed AD, we'd claim it was totally an individual act. All the IFC could do would be to slap him on the wrist." In a not unrelated announcement, a College official estimated that necessary repairs to the houses would cost from $250,000 to $500,000 and said that the College was liberalizing its loan provisions to the fraternities.

Ironically, at their meeting three days before the faculty vote, the Trustees had been prepared to make a statement to the College community expressing concern about student conduct. What dissuaded them, according to later comments by Trustee Robert Kilmarx '50, chairman of the Trustee's Committee on Student Affairs, was testimony from student members of the committee that the situation was improving and that a statement by the Trustees "might undermine the good things that were developing." The good things were the positive influence of increased numbers of women students on the campus and on the fraternities in particular; the new constitution already beginning to work (in an about-face the fraternities had been heard to praise the benefits of "our constitution"); social alternatives to be provided by the new student center in College Hall; student initiatives toward a responsible and workable form of student government; and the Epperson motion itself, which, according to Kilmarx, awakened the fraternities to the problems they faced and encouraged "positive thinking."

ACT IV: When the Trustees take up the faculty vote in February, they will be discussing the fate of 22 fraternities and two sororities. About half of the male undergraduates and a few women belong to fraternities, and the sororities have 150 members. The Trustees will also have to square reports of progress with accounts of disturbing episodes and events. The action of the faculty binds them to no particular course of action. The Trustees can follow the faculty lead, modify it, or interpret it as more a symbolic statement than as a call for immediate action. If past events are any guide, the Trustees do not seem likely to make a final decision without thorough study. Whether they will be satisfied with the evidence now available is the question. (For its part, the Alumni Council, meeting in Hanover on December 1, endorsed a statement acknowledging the "strains" felt by the fraternity system but concluding that the fraternities have "the potential to make a positive contribution to the quality of life at a changing Dartmouth." The authors of the statement felt that developments following the faculty vote "may well be the catalyst that will revitalize the fraternities.")

There is no doubt that the vote has had a profound impact already, perhaps greater than envisioned by Epperson and the rest of the faculty who voted on November 6. Serious thinking is being done about conduct and humane values, what the College stands for, the meaning of community and civilization, and about whether Dartmouth's public image matches its private reality. For the first time in memory the faculty as a group has shown an official concern for the quality of student life. The effects could be transitory or enduring. Shortly after the faculty approved his motion, Epperson said, "Students and faculty should get together now and not be divided." The Alumni Council and many fraternity and sorority members seem to be saying the same thing.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureCrime and Punishment

December 1978 By Tim Taylor -

Feature

Feature'Raucous behavior of a different sort'

December 1978 By Mary Ross -

Feature

FeatureGOOD NEWS

December 1978 -

Article

Article'Most Improved Professor'

December 1978 By NARDI REEDER CAMPION -

Article

ArticleStraight Shooter

December 1978 By D.M.N. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1963

December 1978 By DAVID R. BOLDT

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Cold War and Liberal Learning

November 1961 -

Feature

FeatureA Scientific Centennial for Dartmouth

OCTOBER 1969 By ALLEN L. KING -

Feature

FeatureThe Diminishing Citizen

July 1962 By BASIL O'CONNOR '12 -

FEATURE

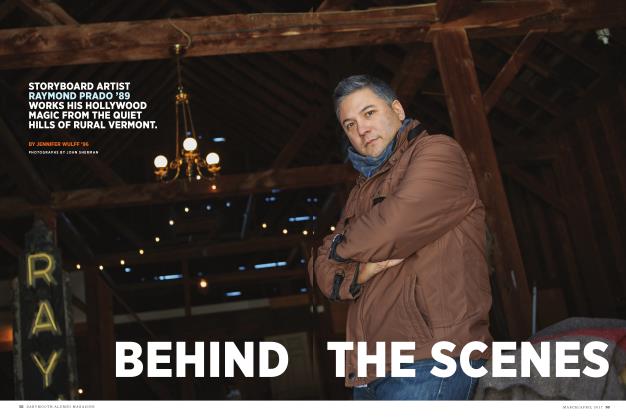

FEATUREBehind the Scenes

MARCH | APRIL 2017 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureTerrorism and the Niceties of Justice

MAY 1982 By Joseph W. Bishop Jr. -

Feature

FeatureWhen Dialogue Turns to Diatribe

MAY 1989 By Larry Martz '54