Miraculously Builded

For the author, plenty of lessons came while collecting stories for a new Dartmouth anthology. Even more came from the book’s co-conspirator, Edward Connery Lathem ’51.

NOVEMBER 1999 David M. Shribman ’76For the author, plenty of lessons came while collecting stories for a new Dartmouth anthology. Even more came from the book’s co-conspirator, Edward Connery Lathem ’51.

NOVEMBER 1999 David M. Shribman ’76For the author, plenty of lessons came while collecting stories for a new Dartmouth anthology. Even more came from the book's co-conspirator, Edward Connery Lathem '51

THE CALL CAME LATE AT NIGHT and the tone of the voice was ominous. We had to meet. In Boston. Soon. For three years I had worked with Ed Lathem, dean of libraries and librarian of the College from 1968 to 1978, putting together a book of reminiscences and tributes, exhortations and pensees, diatribes and manifestos, all intended to provide a taste of Dartmouth in the twentieth century. I knew the man did not bluff. I knew the project was nearing its end. So I accepted the summons. I went to Boston. The very next day. And there, in the USAirways Club lounge atLogan International Airport, we took up a question we simply could not avoid. We confronted the issue of whether the pages of our book, Miraculously Builded in Our Hearts, should contain 38 lines of type or 39.

We gulped a bit, mustered all the courage we could find, and made the fateful decision. We went for 39. And, as Ed's friend Robert Frost 1896 put it in a far less consequential context, that has made all the difference. And now that our book is out now that it is in the bookstores or, more precisely, the Dartmouth Bookstore—l realize that Edward Connery Lathem '51 has made all the difference, not only in our little book but also in the life of our College, and in my own life.

These reminiscences and tributes, exhortations and pensees, diatribes and manifestos, are the leaves of Dartmouth's tree, and here at the autumn of the century Ed and I felt an irresistible need to rake them, to pile them up, to jump into them, and to reassemble the pile again. No one told us to do this. But, then again, no one tells a young child to make his autumnal leaf pile in the first place, or to jump into it. Some deeply imbedded impulse screams: You must do this.

So we did. We looked through the multicolored leaves of this College, through books and magazines, biographies and memoirs, notebooks and scrapbooks, playbills and playbooks. We rummaged through newspapers, we searched through archives. We read letters written by people we never met, we ventured into the closets of people we hardlknew. And to fill a need here and there we commissioned entries especially for our anthology.

All the while we were on the phone to each other, meeting often, sometimes in Washington, sometimes at Dartmouth. Several Saturday mornings Ed hitched a ride with me as I drove from Hanover to Boston. He always returned to New Hampshire by bus, but not until he used the car time to lobby me, beseeching me, for example, not to include a piece I desperately wanted to use, a 1932 speech by the chairman of the University of Chicago's English department that concludes with my favorite sentence in the book: "The outsider sees Dartmouth as the great American college; vivid; the one Rubens in our collection." (I finally won that battle, one of the very few in which he did not prevail. Fortunately, he seldom gloated.)

One day my wife asked: "Are we going to get a letter from Ed Lathem every day for the rest of our lives?" Maybe.

In many ways the book is a companion to the much-loved A Dartmouth Reader, edited by Francis Brown '25, the late editor of The New York Times Book Review, and published in 1969 at the time of the College's bicentennial celebration. Mr. Brown's book reached all the way back to 1769, to the founding

of the College, and left off in the very last year of the tumultuous 19605. But so much has happened since 1969. Since then, the familiar phrase "men of Dartmouth" has come to represent only half the students on campus and the word "blitz" is something students send to each other by computer, not something Hitler did to London or something the football defense did to Princeton or Cornell. Since then, interstate highways and telecommunications have made Hanover far less remote, and the high-octane students recruited in recentyears have made the campus far more yeasty.

Even in restricting ourselves to the twentieth century, though, we faced the problem that haunted Mr. Brown three decades ago: "I felt like the old preacher who, in announcing the hymn, said let's sing all 12 verses, they're all too good to omit any one." The Dartmouth hymnal has only grown since then. There was so much we wanted to include, so little we were willing to discard. Over the months that extended to three years we winnowed and dickered and negotiated and once in a while we even bickered, and though in the end Ed may have won a place for one too many excerpts from presidential speeches and I may have insisted on including one too many tributes to the snow-crusted peaks of New Hampshire, overall we are happy with our literary leaf pile. And we are still speaking to each other, Ed and I.

I'm glad we are. A project like this is an education in its own right, not only in the history of the College but also in the details of making a book out of a pile of literary leaves. The leaves the reminiscences of C. Everett C. Koop '37 courting his wife during his college days; reflections on the black experience at Dartmouth; a remarkable essay by a young woman who was drawn to Dartmouth because her grandfather, class of 1909, insisted that his Dartmouth banner hang in his hospital ward; the memoirs of a Native-American student who belonged to Alpha Chi in the 1980s; the attacks on Dartmouth by The Chicago Tribune (1948) and the Manchester Union Leader (1970); the only thing I ever read by John G. Kemeny that I know to be false (once math students learn the rudiments of a new machine he helped develop, Kemeny wrote in 1966, "they never, if they wish, have to touch a machine again in their entire lives.") provided their own lessons.

All the rest of my education came from Ed Lathem.

These are some of the lessons Ed taught me in three years of hard labor: There is a difference between an introduction and a preface. It is worthwhile no, absolutely essential to assure that there is just the right space between the dots in an ellipsis. (There should be four dots if the ellipsis ends a paragraph.) It is best to regard "washtubs" as a single word, not as two words. Call it Hanover Plain, not the Hanover Plain, but on second reference "the Plain" will do. All that plus one more: The person who worries about getting the many small things right invariably gets the few big things right.

In his final year at Dartmouth, Robert Frost wrote Ed a note: "Research-boy, chronicler, historian all are worth being in an ascending scale. You are certainly off to a good start for the first and even second—-yes and even third. It seems to me for you to decide how far you want to go."

In the end, in one sense at least, Ed decided not to go far. That, too, has made all the difference. He's a New Hampshireman, by birth and by choice, and though he wandered off to Columbia for a master's and to Oxford for a D.Phil., mostly he remained in Hanover, becoming so much more than research-boy, chronicler, and historian. He first touched me in 1969, three years before I arrived on Hanover Plain (please note the correct usage), when I was given a copy of the standard edition of Frost's poetry, edited by a mysterious figure named Edward Connery Lathem. Other books, too, all with a distinctive New England flavor, bear Ed's gentle fingerprints. You cannot examine the lives of Robert Frost or Calvin Coolidge without encountering Ed. You cannot.

On paper or, more likely, on the spine of a book or on its cover, Edward Connery Lathem is a fearsome thing to contemplate. So precise. So sophisticated. So worldly. So otherworldly. So suited for an address that, until he moved his digs to Webster Hall, read simply, 213 Baker Library, Hanover, New Hampshire, For years the very name intimidated me: Two syllables, then three, then two again, as if he were named by poets. Yes, on the spine of a book Edward Connery Lathem is a fearsome thing.

But in person in the long lunches, chowder followed swiftly by parmesan-crusted pan-fried fish, talking over the Ernest Fox Nichols presid ency; in the long white afternoons in his office, going through the boxes of manuscripts; in the long rides, all the way down 89 and then down 93, talking about Dr. Seuss or Erskine Caldwell (both great friends of Ed's), or the time Frost had lunch with T.S. Eliot in London, or the weather, or the way Mt. Ascutney looks in winter there was nothing fearsome about him at all. All those times he was, simply, Ed. One syllable, and a crisp one at that.

I went to Ed for help with this book because I needed someone who knew more than I did; by that standard, almost anyone in the 03755 zip code would have done fine. But my friend and classmate, Peter Gilbert '76, knowing that I admire the editing arts, that I have a weakness for phrases like "the historical College" and the "Wheelock succession," and that the title "Bezaleel Woodward Fellow" on Ed's stationery would intrigue me no end, steered me to him. I knew he was an editor of renown; he knew I was a Trustee of the College. Within a week's time, I wanted Ed as one of the editors in my life. Within a week's time Ed asked me if he could designate me his personal Trustee. I took it to be a metaphor. I think he did, too.

We became more than co-editors. We became co-conspirators. We knew that we needed an extract about the burning of Dartmouth Hall in 1904, and we delighted in the one from The Boston Evening Transcript that referred to the century-old building as "merely a heap of blazing ruins." We chuckled at Mrs. William Jewett Tucker's account of the installation of President Nichols, especially her description of the remarks of the president of the Alumni Association as "of a trivial, facetious, commonplace kind" and her comment, "Fortunately the greater part of it was inaudible." And we could not contain our pleasure at the memoirs of a student who worked his way through Dartmouth at a funeral home, particularly the line: "The only part of the operation I did not relish was sewing the eyes closed."

In the past three years I have often thought that if you were going to invent an Edward Connery Lathem if you decided that such a figure were indispensable to your college you would invent one exactly like the one we have already. Someone whose sense of high purpose makes you think of William Lloyd Garrison, who was known as the Thunderer, but who in person is really a Whisperer. Someone willing to be the guardian for the traditions that matter and to pay no mind to the ones that don't. Someone who worries about just the right size for a plaque on a building. Someone who could serve, with aplomb, as College usher at graduation, toting around Lord Dartmouth's Cup with grace and dignity. Someone Jim Wright could search out on the morning just before his first Commencement to ask whether the provost or the chairman of the board should shake graduates' hands if the president grew weary. (Ed's counsel: die chairman of the board.) Someone, now that you mention it, willing to wear a white tie every day. That's why I realized that our little meeting in the USAirways Club wasn't really about 39 lines versus 38. It was about doing things right, about taking the time to worry about the detail that would only seem significant if it weren't attended to correctly, about caring enough. The meeting was Ed's way of saying that we weren't finished yet, that we couldn't let up our attention, that the price of excellence, as Jefferson might say, was eternal vigilance. At 11:30 in the morning, when my flight arrived, I had no strong views about whether a printed page should have 39 lines or 38.

Indeed, I had never given the subject so much as a moment's thought. But after all the page proofs were spread out in the lounge, after all the alternatives were examined, after all the explanations were offered, Iwas doctrinaire. Ithad to be 39. Just had to be.

President emeritus Jim Freedman told me just the other day that he grew to dread the idea of writing a single sentence without subjecting it to Ed's review. I know what he means. In both our cases, what began as a reliance on Ed's eye and ear became so great that it eventually became a dependence. So I complete this essay with trepidation; it's being sent to the editor of the magazine without Ed's editing. No doubt he'll hate it. The man in the white tie has no respect for frippery, or for flattery. God how I love him.

AT THE AUTUMN OF THE CENTURY ED AND I FELT AN IRRESISTIBLE NEED TO RAKE UP DARTMOUTH'S LITERARY LEAVES AND JUMP INTO THEM.

EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM IS A FEARSOME THING TO CONTEMPLATE. SO PRECISE. SO SOPHISTICATED. SO WORLDLY. SO OTHERWORLDLY.

College Trustee DAVID SHRIBMAN is the Washington bureau chief and assistant managing editor for The Boston Globe.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

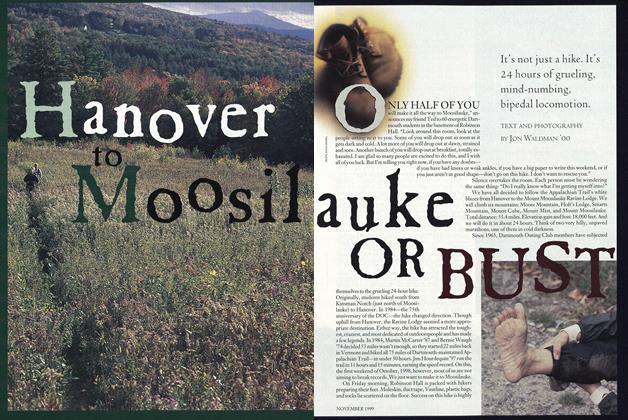

Cover StoryHanover to Moosilauke or Bust

November 1999 By Jon Waldman ’00 -

Feature

FeatureBadly, He Wrote

November 1999 By Rich Barlow ’81 -

Feature

FeatureWebster in the Raw

November 1999 -

SYLLABUS

SYLLABUSThe Undead

November 1999 By Kathleen Burge ’89 -

PRESIDENTIAL RANGE

PRESIDENTIAL RANGEThe Numbers Game

November 1999 By President James Wright -

Curmudgeon

CurmudgeonThe Problem with the Dorm-Room Fridge

November 1999 By Noel Perrin

David M. Shribman ’76

Features

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Medical Metamorphosis

December 1959 -

Feature

FeatureSports Style-Setter

FEBRUARY 1967 -

Feature

FeatureROBERTA STEWART

Nov - Dec -

Cover Story

Cover StoryBROKEN CLAY PIPES

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIn Ledyard's Wake

JUNE 1983 By Jean Hanff Korelitz '83 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryBlack Dan's Reunion

June 1989 By Jim Collins '84