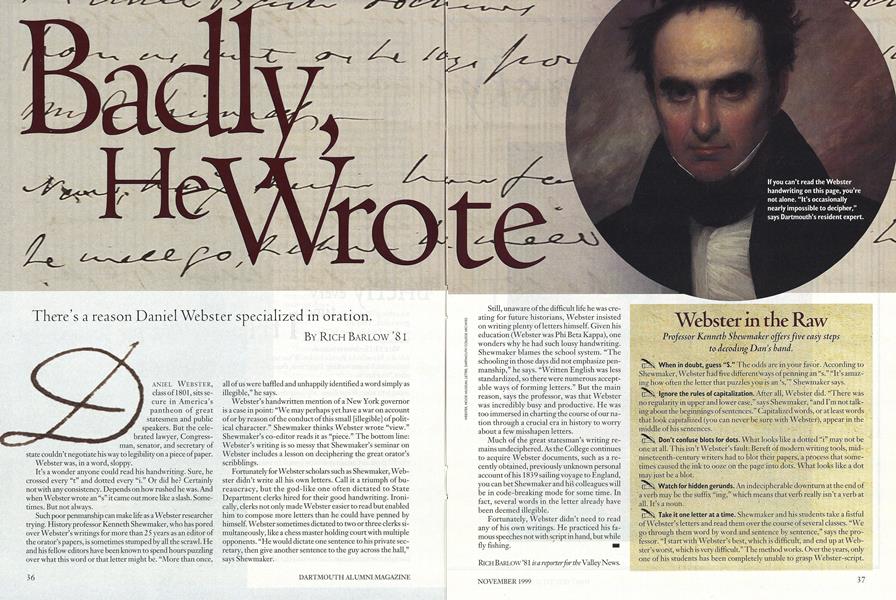

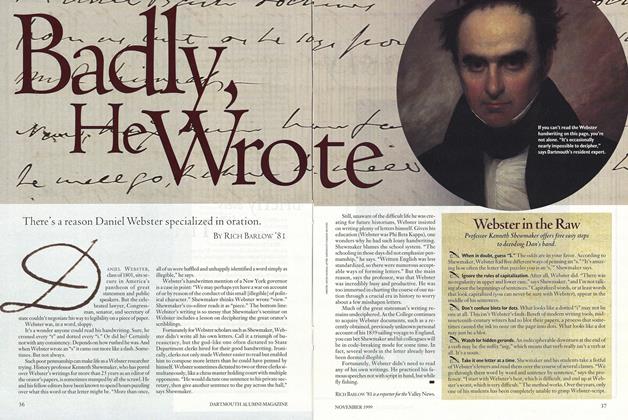

Badly, He Wrote

There’s a reason Daniel Webster specialized in oration.

NOVEMBER 1999 Rich Barlow ’81There’s a reason Daniel Webster specialized in oration.

NOVEMBER 1999 Rich Barlow ’81There's a reason Daniel Webster specialized in oration.

statesmen and public brated lawyer, Congressman, senator, and secretary of state couldn't negotiate his way to legibility on a piece of paper.

Webster was, in a word, sloppy. It's a wonder anyone could read his handwriting. Sure, he

crossed every "t" and dotted every "i." Or did he? Certainly not with any consistency. Depends on how rushed he was. And when Webster wrote an "s" it came out more like a slash. Sometimes. But not always.

Such poor penmanship can make life as a Webster researcher trying. History professor Kenneth Shewmaker, who has pored over Webster's writings for more than 25 years as an editor of the orator's papers, is sometimes stumped by all the scrawl. He and his fellow editors have been known to spend hours puzzling over what this word or that letter might be. "More than once, all of us were baffled and unhappily identified a word simply as illegible," he says.

Webster's handwritten mention of a New York governor is a case in point: "We may perhaps yet have a war on account of or by reason of the conduct of this small [illegible] of political character." Shewmaker thinks Webster wrote "view." Shewmaker's co-editor reads it as "piece." The bottom line: Webster's writing is so messy that Shewmaker's seminar on Webster includes a lesson on deciphering the great orator's scribblings.

Fortunately for Webster scholars such as Shewmaker, Webster didn't write all his own letters. Call it a triumph of bureaucracy, but the god-like one often dictated to State Department clerks hired for their good handwriting. Ironically, clerks not only made Webster easier to read but enabled him to compose more letters than he could have penned by himself. Webster sometimes dictated to two or three clerks simultaneously, like a chess master holding court with multiple opponents. "He would dictate one sentence to his private secretary, then give another sentence to the guy across the hall," says Shewmaker.

Still, unaware of the difficult life he was creating for future historians, Webster insisted on writing plenty of letters himself. Given his education (Webster was Phi Beta Kappa), one wonders why he had such lousy handwriting. Shewmaker blames the school system. "Thschooling in those days did not emphasize penmanship," he says. "Written English was less standardized, so there were numerous acceptable ways of forming letters." But the main reason, says the professor, was that Webster was incredibly busy and productive. He was too immersed in charting the course of our nation through a crucial era in history to worry about a few misshapen letters.

Much of the great statesman's writing remains undeciphered. As the College continues to acquire Webster documents, such as a recently obtained, previously unknown personal account of his 1839 sailing voyage to England, you can bet Shewmaker and his colleagues will be in code-breaking mode for some time. In fact, several words in the letter already have been deemed illegible.

Fortunately, Webster didn't need to read any of his own writings. He practiced his famous speeches not with script in hand, but while fly fishing.

If you can't read the Webster handwriting on this page, you're not alone. "It's occasionally nearly impossible to decipher," says Dartmouth's resident expert.

RICH BARLOW '81 is a reporter for the Valley News.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

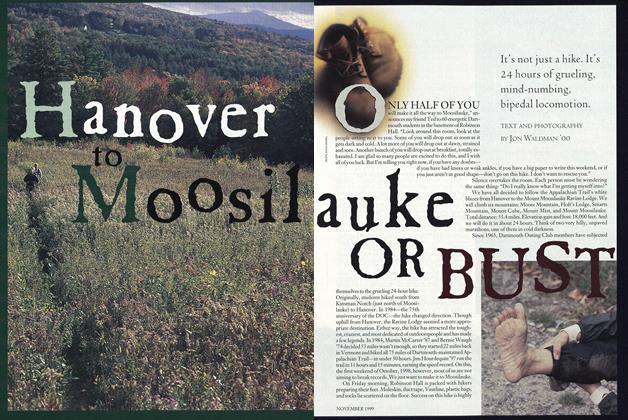

Cover StoryHanover to Moosilauke or Bust

November 1999 By Jon Waldman ’00 -

Feature

FeatureMiraculously Builded

November 1999 By David M. Shribman ’76 -

Feature

FeatureWebster in the Raw

November 1999 -

SYLLABUS

SYLLABUSThe Undead

November 1999 By Kathleen Burge ’89 -

PRESIDENTIAL RANGE

PRESIDENTIAL RANGEThe Numbers Game

November 1999 By President James Wright -

Curmudgeon

CurmudgeonThe Problem with the Dorm-Room Fridge

November 1999 By Noel Perrin

Features

-

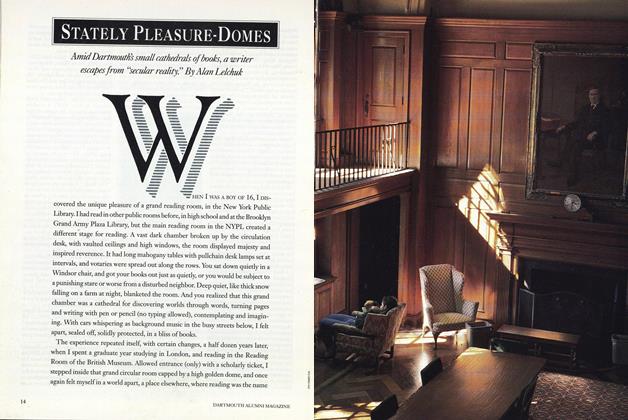

Feature

FeatureStately Pleasure-Domes

MAY 1990 -

Feature

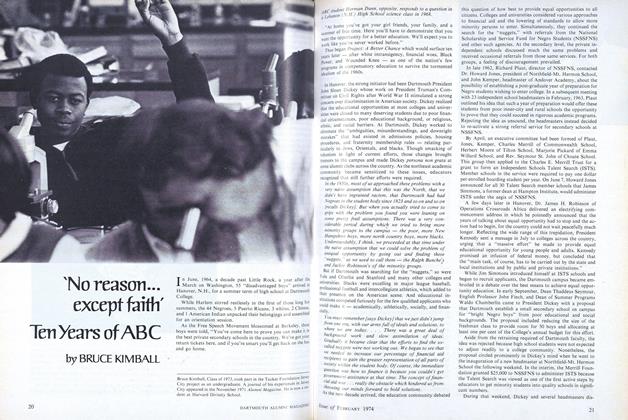

Feature‘No reason... except faith' Ten Years of ABC

February 1974 By BRUCE KIMBALL -

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH SONGS

APRIL 1963 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21 -

Cover Story

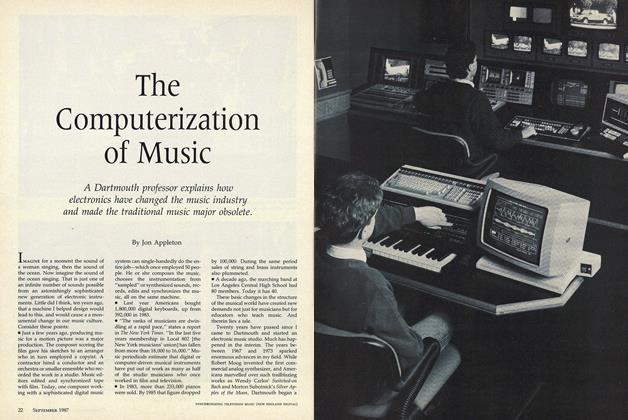

Cover StoryThe Computerization of Music

SEPTEMBER 1987 By Jon Appleton -

Features

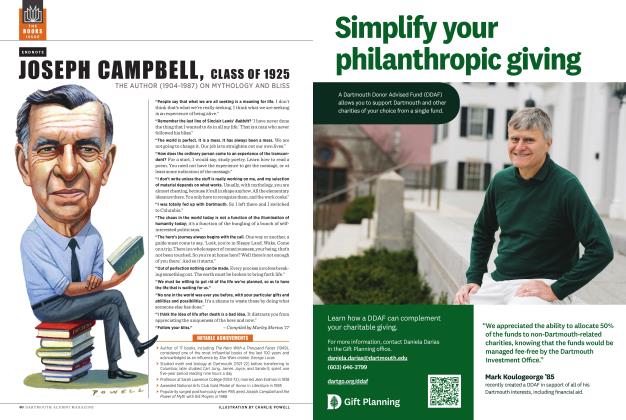

FeaturesJoseph Campbell, class of 1925

JULY | AUGUST 2024 By Marley Marius ’17 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryRethinking The Stacks

December 1992 By Tig Tillinghast '93