Vampires bite to the core of human conflicts.

IT WAS SUPPOSED to be an indulgent vacation among friends, a summertime trip through Switzerland and Italy with leisurely stays at lakeside villas. But when a few days of rain trapped the travelers indoors, tempers began to glow. Most of the friends were writers, and one of their companions, a doctor, sulked through their long discussions of poetry. To pass the time, the friends began reading ghost stories. One of them suggested they pen their own tales of terror.

The friends on vacation in June 1816 were Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and Shelley's wife, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley. Their stories had bite. Byron's "Fragment of a Novel" emerged as one of the first modern vampire stories. The cranky doctor, John Polidori, produced "The Vampyre," a short story based on Byron's tale. It featured a vampire who bears an uncanny resemblance to Byron. (Mary Shelley also published the story she began in Switzerland: Frankenstein.)

The vampires Byron and Polidori captured on the page continued a long tradition of horror. Vampires have been around for more than two millennia. Ancient Chinese folklore mentions vampire-like creatures who jumped on the backs of humans and sucked their life force. "Vampires, or undead creatures, are phenomena that have existed in many different cultures and over a long period of time," says professor Gerd Gemiinden of the German department. "That allows you to use them as an entry to study cultural differences."

Some students come to Gemiinden's vampire course, "The Undead," hoping to sink their teeth into popular culture. Some have read all of Ann Rice's novels. Most of the students love horror flicks. A few even claim to belong to a secret werewolf society.

But students quickly find that Gemiinden brings the undead to life to talk about complex human matters: multiculturalism and assimilation; sexuality and constructions of gender; colonialism and post-colonialism, to name only a few. Since Freud and some of his disciples wrote about vampires, Gemiinden even introduces his class to basic concepts in psychoanalysis. One of Freud's followers, Ernest Jones, saw vampires as figures who allowed people to do what they normally repressed especially sexually. That's what makes vampires both frightening and intriguing Jones argued in his 1920 essay, "On the Vampire." The theme of repression "resonates very much with Puritan morals and ethics," says Gemiinden. "I think that's why, especially in the United States, vampires seem to be so fascinating, and also why in England in the nineteenth century, vampire fiction took off."

In modern times, vampires have been portrayed as undead creatures who attack people and suck their blood. They are repelled by garlic and crosses. They hate sunhght. Their passion for darkness, though, is a relatively new phenomenon. In fact the most famous modern vampire, Bram Stoker's Dracula (1897), cruised the streets of London in the daytime. F.W. Murnau's 1922 film Nosferatu, A Symphony of Horror created the first vampire destroyed by sunlight. Nosferatu can be seen as a self-conscious allegory of the process of filmmaking, Gemiinden says. Like the vampire, filmstock is destroyed by sunlight, yet subjects captured on film become immortal. "They remain on film forever," says Gemiinden. Considered in a more historical context, the 1922 film can also be seen to comment on World War I—Nosferatu conjures up the millions who died in that war, connecting die theme of improper burial that gives rise to vampires with the inability to come to terms with the trauma of war.

Vampire tales rose anew in the 1980s and 19905, most notably with Anne Rice's novel Interview with a Vampire. (Tom Cruise played the cape-clad, fang-toothed monster in the Hollywood version.) Gemiinden links the vampire's return to contemporary hot-button debates over multiculturalism, feminism, and homosexuality. At the heart of these debates, he says, is the question of whether culture demands assimilation. "The vampires in these films and books often take on the aura of a renegade, someone whose status as an 'other' is idealized," Gemiinden says. "At a time when everybody feels he or she belongs to a minority under siege, that figure becomes very attractive. But you also see the forces that are at work that require people to assimilate their identities to the melting pot. Vampire narratives are often blueprints for passing as something or for being someone or something one really is not."

In Jewelle Gomez's The Gilda Stories, published in 1991, the protagonist is a young, black, female slave from Louisiana who is transformed into a vampire. She is a thoughtful vampire. She does not kill her victims. She drinks their blood but leaves them with pleasant dreams to erase the trauma of her attack. The novel traces the history of the United States through the eyes of this woman, who encounters everything from the deep racism of the South before the Civil War to die environmental issues of today. "The answer the novel gives to these problems is that the vampire is a very special breed that must fight extinction," Gemiinden says. "The vampire, afraid of being hunted and killed by humans, can only succeed if she retreats into a community of likeminded people. It's about the preservation of a certain culture."

Even Stoker's Dracula addressed the political issues of the day. "The female vampire that is produced by Dracula is a threat to the males who hunt her down," Gemiinden says. "It was a comment on the new woman that was emerging in the late nineteenth century. But you can also see it as a comment on the crumbling English empire. One threat the novel articulates is the East 'the other'—buying up real estate in the West, learning the Western language, and outsmarting the British at their own game."

In recent years, vampire films have achieved cult status in the gay community and are often featured at gay film festivals. According to Gemiinden, gay men and women relate to vampires for their ostracism from society. "The vampire is a figure that can pass for human, but those who are vampires can read the signs," he says. "Gay people in society can out themselves, but sometimes do not want to and can pass for straight." Vampires themselves are starting to come out of the closet. Homoeroticism is explicit in many of Rice's novels. In the 1983 movie The Hunger, a bisexual female vampire seduces characters played by David Bowie and Susan Sarandon.

In the past, vampire stories often ended when the vampire died from a stake driven through his heart. But now, partly in deference to our sequel-happy times, more and more vampires live to see the end of the story. Their future, Gemiinden says, depends on us. "As long as they continue to hold their attraction for us," he says, "they will not die."

"i am Dracu Ia," bela lugosi intoned in the title role of the 1931 film. Was he a scary monster or an agent of assimilation?

KATHLEEN BURGE is a freelance writer who lives in Norwich, Vermont.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

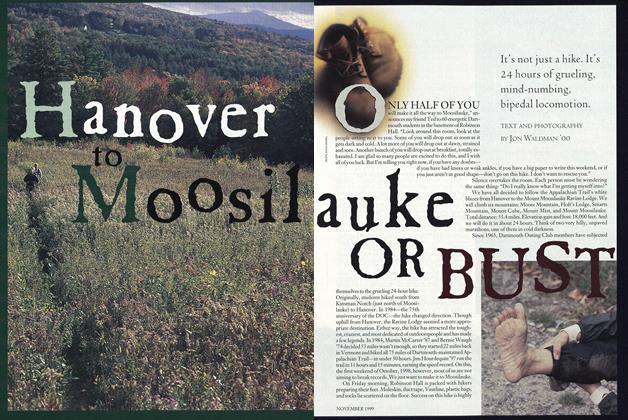

Cover StoryHanover to Moosilauke or Bust

November 1999 By Jon Waldman ’00 -

Feature

FeatureMiraculously Builded

November 1999 By David M. Shribman ’76 -

Feature

FeatureBadly, He Wrote

November 1999 By Rich Barlow ’81 -

Feature

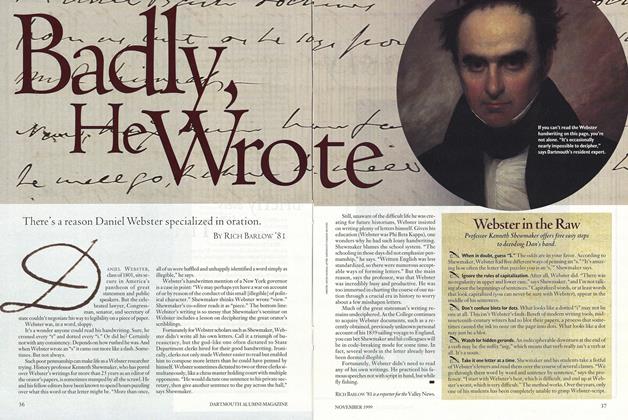

FeatureWebster in the Raw

November 1999 -

PRESIDENTIAL RANGE

PRESIDENTIAL RANGEThe Numbers Game

November 1999 By President James Wright -

Curmudgeon

CurmudgeonThe Problem with the Dorm-Room Fridge

November 1999 By Noel Perrin