"The world is a living system. . . .

"If there is any matter that is the first business for science and government alike, it is that simple fact, increasingly ignored in the mad scramble for economic gain,' George M. Woodwell '50 writes in an article on "Ecosystems and World Politics," which appeared in last month's Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America.

"Management of the world's resources is unquestionably in the hands of the exploiters," he contends. "The assumption is that compromise among reasonable men provides a sufficient basis for regulating the resources of the environment, quite irrespective of any basic laws of nature. . . ."

Research into the structure and function of natural ecosystems, which fix - through photosynthesis - and distribute solar energy for the support of all life, and the degradation of those systems by the intrusion of man and his artificial constructs is the professional concern of Woodwell, a third-generation Dartmouth man who is Senior Ecologist at the Brookhaven National Laboratory and Lecturer in Ecology at Yale. His interest lies, quite elementally, in the future of man.

"I would suggest," he says, "that the dependence of man on nature is, more than the crisis of energy, more than the developing crisis of world economics, the emergent scientific and political issue of the next years.... I suggest that the earth's biota is our single, more important resource. While protecting it will not assure wealth and grace for man, its decimation will assure increasing hardship for all."

Woodwell directs a large research program into the nature of surface ecosystems and how they work within their own components and in relation to other systems. A longterm project which has engaged much of his attention since he went to Brookhaven in 1961 is a study of the effect of chronic gamma radiation on two widely differing ecosystems - a mature forest and an "old field." Continuing observation of the relative sensitivity of species within the systems to varying intensities of radiation has shed new light on the results of prolonged exposure to pollutants - be they radiation, toxic smog, persistent pesticides, or the acid rain caused by atmospheric sulphur and nitrate, deposited presumably by automobile emissions and the burning of fossil fuels.

The results of such leakages from man-dominated systems, Woodwell has found, is the simplification of the structure of ecosystems. Damaged or eliminated first are the specialized, the large-bodied, the slow-growing species of animal and plant life. Favored are the tough, resistant, small, fast-growing species commonly regarded as pests - low shrubs, weeds, crab-grass, rodents and insects which compete with man for crops.

The pattern clearly observable in the irradiated forest was "a systematic dissection..., strata being removed layer by layer. Trees were eliminated at low exposures, then the taller shrubs, then the lower shrubs, then the herbs, and finally the lichens and moss." The pattern was analogous to that noted in burned out or cut over woods, the reduction of forests exposed to toxins in the air of the Los Angeles basin, or the dense stands of bamboo which'replaced the tree canopies of Viet Nam after repeated applications of herbicides. In each case, the soils lost their capacity to retain nutrients recycled from the system and built up over millenia. The nutrients in turn leaked into neighboring systems, eutrifying streams fed by the watersheds, reducing the life-supporting potential of both.

To prevent further degradation of ecosystems, Woodwell and many of his scientific colleagues advocate an international policy by which no man-dominated system would be permitted to leak toxins, essential nutrients, dirty air, or dirty water - "thinkable, the hysteria of economists notwithstanding."

"Biologists need not be reticent in representing the interests of life," he urges. "The changes are occurring rapidly; the patterns are clear; the causes, known. The questions are of magnitudes. We know enough now to question, even to deny, the current design of urban systems that leak nutrient elements and toxins into the environment....to reverse a policy of exploiting the assimilative capacity of streams, lakes, and oceans.... to reverse a complex of policies, national and international, that tend to allow the effects of man to diffuse more widely around the earth. We know now that the establishment of reactors on estuaries or on the continental shelves is precisely in this context and not acceptable. So are oil wells in the oceans; so is seabed mining; so are ocean outfalls for sewage."

"We know enough now," Woodwell asserts, "to offer genuine guidance with basic principles of ecology to the counsels of reasonable men . . . until it becomes clear to the public and to them that the world is run by living systems that operate under discoverable laws that compromise does not repeal."

George Woodwell's irradiated foreststands in stark contrast to Robert Pack'suncorrupted Corrupted grove of Vermont birches.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTomorrow: A Call for Limited Growth

April 1974 By DENNIS L. MEADOWS -

Feature

FeatureUnquestionably the ugliest Building in Hanover"

April 1974 By JOHN R. SCOTFORD, JR -

Feature

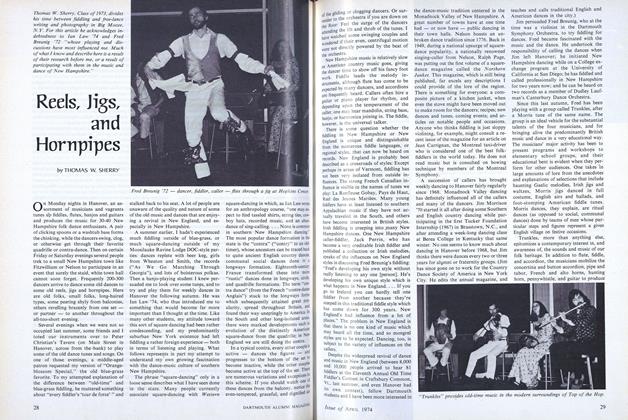

FeatureReels, Jigs, and Hornpipes

April 1974 By THOMAS W. SHERRY -

Feature

FeatureYesterday: A Policy of Consumption

April 1974 By GORDON J. F. MacDONALD -

Feature

FeatureToday: Views of an Embattled Oilman

April 1974 By WILLIAM K.TELL JR. -

Feature

FeaturePoseurs, Impostors, and Scalawags

April 1974 By MARY BISHOP ROSS

M.B.R.

-

Article

ArticleOil Man Caracas

November 1974 By M.B.R. -

Article

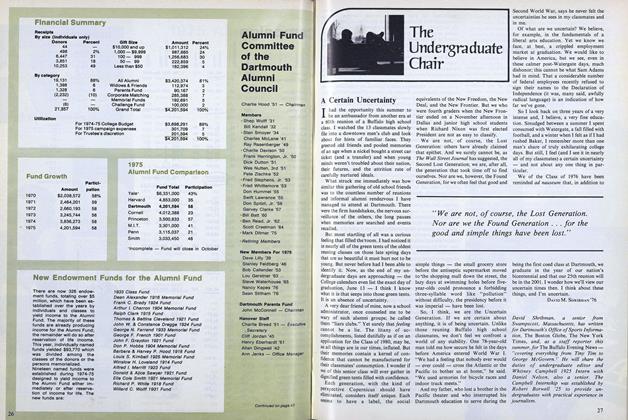

ArticleA Page for all Fords

May 1975 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleOf Ancient Mariners... and Monsters of the Deep

September 1975 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleEqual Opportunity: efforts to make it more equal

June 1976 By M.B.R. -

Feature

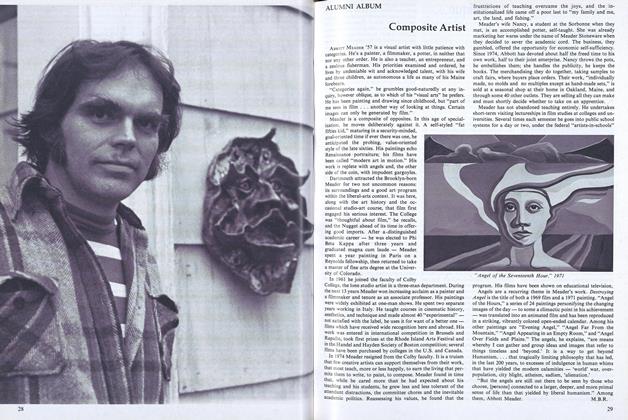

FeatureComposite Artist

February 1977 By M.B.R. -

Article

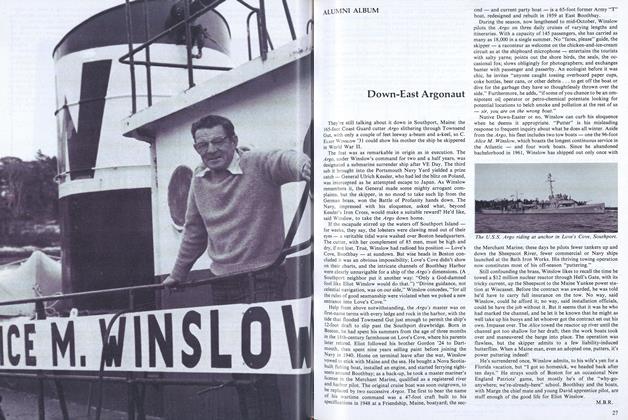

ArticleDown-East Argonaut

March 1977 By M.B.R.

Features

-

Feature

FeatureTHE ALUMNUS/A

April 1960 -

Feature

FeatureNever Let Go

February 1977 -

Feature

FeatureThe Battle of Bunker Hill

June 1975 By LEWIS STILWELL -

Feature

FeatureOISER: Massaging the Media

May 1977 By PIERRE KIRCH -

Feature

FeatureAfter Eleven Commencing

June 1995 By Regina Barreca '79 -

Feature

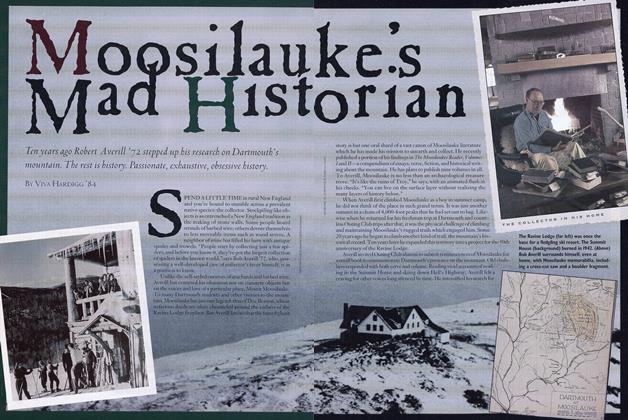

FeatureMoosilauke's Mad Historian

OCTOBER 1999 By Viva Hardigg '84