With the amateurfoundation of thesport shiftingunder them} themembers of theDartmouth men'srugby club set theirsights on anational title.

EARLY IN THE SECOND HALF against Northeastern on a bright Indian summer afternoon in Boston the score is still tight, but the Dartmouth men's rugby team is on the attack. Dartmouth keeps the play flowing through a series of lateral passes that accelerate the ball down the field. Performing a choreographed dance that has been rehearsed over and over, each player receives the ball and then lets it go just before making contact with the opposition, all in one fluid motion. Dartmouth players quickly close around—"rack over"—a tackled teammate to prevent Northeastern from regaining the ball. A fresh attack is launched in seconds.

Northeastern is proving to be a resilient and tenacious opponent. At the moment they couldn't care less that they are in last place in New England or that Dartmouth hasn't lost a league game in more than four years. Northeastern doesn't even have a regular coach—but they do have a full gallery of sorority sisters in attendance, and there is nothing quite like testosterone to fuel a man's fighting spirit. After the fourth consecutive phase of attack Dartmouth finally creates an overlap. With only one man to beat and 30 meters to the goal line, co-captain Kevin Whitcher '99 draws the last defender toward him. An instant before absorbing a bone-jarring tackle Whitcher releases the ball to a surprise winger, 6-foot, 250 lb. prop-forward Risana Zitha '99. A prop's traditional place—like an offensive lineman's in football—is at the front of a scrum pushing his guts out or buried in a ruck pushing his guts out. But the modern game of rugby requires a complete repertoire of skills, including the speed and agility of the "wingers" who run and pass the ball in the open field. Any player can turn up anywhere once play has started.

"Props aren't supposed to be on the wing," a surprised Dartmouth alumnus says on the sideline. "The whole time I played prop at Dartmouth they just told me to push, ruck, and not to run with the ball. In four years I never scored a single try."

Apparently neither has Zitha, but he is only 30, 20, ten meters from his first one. The huge South African sprints down the sideline like a scared springbok with a hungry lion on his heels, directly in front of an astonished assembly of alumni, parents, teammates, and coaches. The Northeastern fullback closes in on Zitha and tries to force him out just short of the goal line, but the fleet-footed prop lunges for the corner, the ball outstretched in front of him. As quickly as he lands he is back on his feet, dancing the fox-trot and bellowing, "Who's your daddy? Who's your mother-loving daddy!?"

In nearly 20 years of playing and watching rugby around the world I've never seen a performance quite like this one. In the Dartmouth players' own vocabulary, Zitha's emotional rejoicing is decidedly "New School"—and this, from the player whose appointed position on the club is "Keeper of the Old School. "But before the laughter and stings from the high-fives have subsided on the Dartmouth sideline the referee has disallowed the try. He has judged that Zitha's wide backside touched the corner flag before he touched the ball down, and awards a 22-meter drop-out for Northeastern. The big fellow is heartbroken but there is no time to lament. Play quickly recommences, and Zitha has a job to do.

Zitha's position as Keeper of the Old School is an important one, as any of the alumni who mingle with the new players on the sideline at every Dartmouth rugby game will attest to. Alumni are protective of the student-run organization—the Dartmouth Rugby Football Club, or DRFC—whose proud tradition dates back to 1951. They are defensive about anything that threatens the club's independent nature. In the "old days" the captains ran the practices, or didn't, depending on their character. Students organized overseas tours to places like England and the Bahamas. The DRFC made an appearance on the Ed Sullivan show after touring England in the late' 50s and received a special citation from President Eisenhower. In the early '80s, when a national collegiate rugby championship was created, alumni allowed the club to bring in visiting coaches to improve its game. It paid off. Twice in the mid-'80s Dartmouth finished second in the country, narrowly losing to rugby powerhouse Cal Berkeley in the final.

I'm a new assistant coach at Dartmouth, alongside assistant Brian Hightower and Wayne Young '73, now in his seventh season as head coach. While too many college teams in the country, like Northeastern, are coached by a senior who has been playing for maybe three years and knows more than the newer players, Dartmouth has the privilege this year of having three experienced coaches. Hightower played professionally in New Zealand and is now a member of the U. S. National team. After a career of playing in France, New Zealand, and South Africa, I played against Brian in several international competitions while representing Hong Kong. Wayne Young learned his rugby from the hard-knock Polynesian rugby school in Hawaii, after co-captaining the football team and playing baseball for Dartmouth in the College World Series in the early '70s. Our job is to coach and help the students manage the club, including planning the international tours. An alumni board of governors provides guidance.

The position of "Keeper of the Old School" has evolved with the DRFC. No longer responsible for preventing interaction with the women's rugby club, the position today is more subtle, more complex. The Keeper is charged with preserving traditional social roles and the friendly approach to the game, even as the women and men have begun training together, even as the competition and demands of the sport have become intense. This tension can be seen in the plans for the new clubhouse, as well. The $1.3 million facility will be a thoroughly modern facility serving both men and women, and it will provide the thoroughly traditional postgame socializing space that Dartmouth has never had.

Old School versus New School isn't an issue just at the DRFC; it's a hot topic around the rest of the rugby community, too. Only four years ago the sport gave up its guarded amateur status after years of bitter debate. The head of the International Rugby Board (IRB), the top Keepers of the Old School as it were, had long seen professionalism as a threat to amateurism. There is an expression in rugby that no individual is bigger than the game, and when the IRB looked at professional sports in Europe and America it saw the opposite. Rugby has a tradition of being a sport that is measured in friendships, whether expressed through after-match receptions and singing with opponents or gathering with Old Boys at yearly weekend tournaments where playing the second day is a finable offense. The attachment to the game is a lifelong affair. And rugby has always been a players' game. The Dartmouth men and women field over eight sides every weekend during the season and everybody who practices gets a game. There is an unwritten rule that a player of any caliber who turns up at any club around the world will be looked after by the receiving club, and there is a circuit of players, men and now women, too, traveling the world using their rugby boots as passports. Rugby players find jobs through other rugby players, on construction sites and in investment houses. The Keepers of the Old School do not want this culture of camaraderie diminished.

But rugby experienced a surge in popularity after the inaugural World Cup in 1987, and subsequent television and sponsorship revenues added fuel to the expansion. Modernists in the game saw the head of the IRB as Keepers of the Dead Wood. It was inevitable with so much money in the game and with the full-time demands on players in rugby nations like New Zealand and South Africa that amateurism had to give way. In 1995, after years of under-the-table payments to players, it officially did. The quality of play has skyrocketed.

Although American colleges continue to be slow to support the sport—even when rugby has more participants than any other sport on campus—the reverberations of the changing game are being felt. Rugby is now a varsity sport at Cal Berkeley and other universities; several schools award scholarships; professional coaches are becoming more common and more involved. Dartmouth's best players have a shot at playing in the pros.

A fine line separates the two schools of thought at the DRFC, and nobody treads the line better than co-captain Mark Oldham '99, known to his teammates simply as "RS," which stands for "Rugby School." Mark is an authentic Pom who grew up on a steady diet of Yorkshire pudding and rugby while attending the English boarding school that gave birth to the game. That was where, in 1823, a New School-minded student named William Webb-Ellis had the cheeky notion to pick up a soccer ball and run down the field with it. Before depositing the ball at the other end of the field he was clobbered by one of his irate classmates. The two boys found pleasure in the experience, and the game caught on. American football was born from rugby, as were other equally strange full-contact sports played in foreign countries that you can see at odd hours on cable television.

Today rugby is played with 15 players on a side. There are eight forwards whose principal job is to win possession of the oval, slightly-larger-than-football-sized ball when it is put into play. Seven backs spread across the field in a line receive the ball after the forwards win it. Typically, the more fleet-footed backs try to beat the opposition back-line with set running plays. Once play starts it doesn't stop until there has been an infraction such as a forward pass, off-sides, or blocking, or if the ball is run or kicked out of bounds. A touchdown is called a try and is worth five points. The kick after the try, called a conversion, is worth two points. A successful penalty kick through the goal posts is worth three points. Drop-kicking the ball through the opposing goal posts during play is also worth three points.

As a captain, RS must keep his teammates enthusiastic through a long campaign—with little recognition from the school, just for the fan of it. Three weeks of double-sessions in early September are followed by four practices a week and a dozen games during the fall season. Through the winter the club practices in Leverone field house late at night after the varsity sports have finished for the evening. In March the club makes an overseas trip to prepare for the national playoffs in April. The DRFC, based on its fall seasons, has qualified for the national tournament's "Sweet 16" round for three years in a row. The club is currently ranked number six in the country.

None of this was on the minds of the Dartmouth players as they finally pulled away and beat Northeastern last October, 47-5. Now, on a blustery November afternoon in Amherst, Massachusetts, the DRFC is in the Northeastern championship final against its nemesis, Army. The Dartmouth women's team has just won the women's title, earning a spot in their Sweet 16 in the spring, and the girls have joined a large crowd of alumni, parents, and friends on the sidelines urging the men to duplicate their efforts. Army holds the lead with only ten minutes remaining, and the DRFC needs an emotional jolt. Risana "Big Daddy" Zitha strips off his warm-up suit, paces the sidelines, and enters the game with a big cheer from the sideline. In the last minute of the game Zitha finds himself once again in the clear on the sideline with whitcher, but this time there are 80 long meters in front of him. The Army cover-defense closes the gap, forcing whitcher to the sideline just short of the goal line. In desperation to keep the ball alive, whitcher flings it back over his head, just over the outstretched fingertips of Zitha. The ball falls to the feet of the true winger, team flier Jeff Kinkaid '01, who has been following the play from behind. Kinkaid toes the ball forward with a soccer kick, recovers it, then dives between two Army defenders to touch the ball down for the try and the last-moment victory. After the 80-meter sprint Zitha is too tired to dance the fox-trot; everybody on the sidelines is doing it instead. Zitha settles for a bear hug with Whitcher, followed by a humble Old School trot back down the sideline.

At the end of a gut-busting scrum, Dartmouth gains possession

Assistant coach STUART KROHN, a former national player for HongKong, is a student in Dartmouth MALS program.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

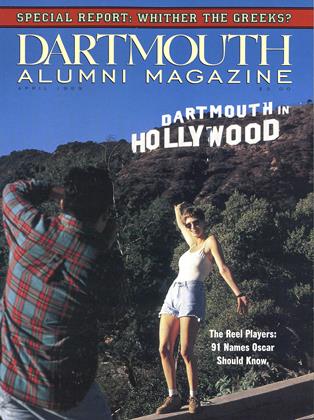

Cover StoryBig Green in Tinseltown

April 1999 By Holly Sorensen '86 -

Feature

FeatureUFOs Are Real!

April 1999 By James Zug '91 -

Feature

FeaturePeople of the Book

April 1999 By Michael Loventhal '90 -

On the Hill

On the HillThe New Social Order

April 1999 -

Article

ArticleA Greek Tragedy

April 1999 By Kevin Goldman '99 -

Article

ArticleBuilding Community

April 1999 By James Wright

Features

-

Feature

FeatureImpacts simply positive

MAY 1982 -

Feature

FeatureRoommates

SEPTEMBER 1999 -

FEATURES

FEATURESDream Team

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2022 -

Feature

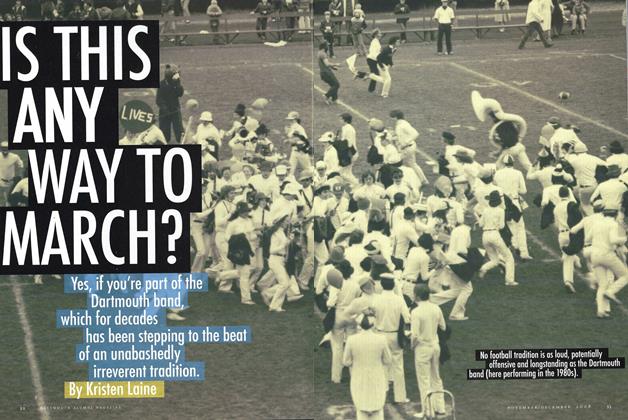

FeatureIs This Any Way To March?

Nov/Dec 2008 By Kristen Laine -

FEATURE

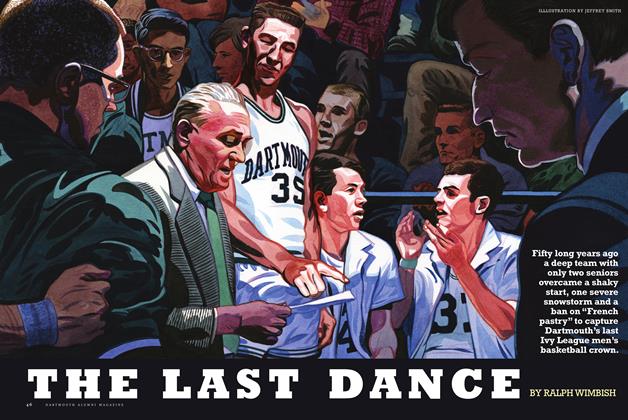

FEATUREThe Last Dance

Mar/Apr 2009 By RALPH WIMBISH -

Feature

FeatureWORLD UNDERSTANDING: A Job for Mass Communications

OCTOBER 1966 By WALTER WANGER '15