Once again the national press flocked to Hanover for a story too good to resist. "The Slow Taming of AnimalHouse " proclaimed The NewYork Times. "Animal House Fraternity Must Go Coed," trumpeted USA Today. The trouble is, they used the wrong movie. Amore apt choice would have been the 1967 classic Cool Hand Luke, which included Strother Martin's memorable line: "What we have here is a failure to communicate."

Lost in the Animal House din was a more significant story: the announcement of Dartmouth's commitment to spend tens of millions of dollars to overhaul an anachronistic social system that is increasingly out of step with other elite schools. Roughly half of the College's students are affiliated with Greek houses, a far higher percentage than at any of the other Ivies. Despite the fact that their parties are open to all students, male fraternities—nineteenth-century holdovers—own 80 percent of the social space on Webster Avenue. Few other options or social spaces exist elsewhere on campus to serve undergraduates. Graduate and professional students are all but forgotten. As one professor said, "The system is a dinosaur."

At a special meeting of the faculty on February 18, President James Wright quipped that he had heard criticism of the Trustees' initiative on only three points: "process, substance, and the way it was communicated." "I regret that people thought we were deliberately hiding something," he said. After two hours of discussion—ranging from the vagueness of the principles to concerns about alienating students-the faculty voted 82-0 (plus six abstentions) to support the five guiding principles described in the Trustees' statement:

• There should be greater choice and continuity in residential living and improved residential space.

•There should be additional and improved social spaces controlled by students.

• The system should be substantially coeducational and provide opportunities for greater interaction among all Dartmouth students.

• The number of students living off campus should be reduced.

• The abuse and unsafe use of alcohol should be eliminated.

The miscommunication began on February 9 when the Trustees' statement and a letter from the president filled students' Hinman boxes. The initial response wasn't a scream, or even a voice of protest. It was silence. Sending a broadsheet via Hinman is not the way to get student attention in 1999 on a campus where most important announcements come via Blitz Mail. Many students didn't pick up their Hinman mail that day, or else tossed it after a quick skimming. Those who actually read the announcment had a hard time figuring out what it meant. Even after President Wright parsed the document for The Dartmouth and the paper ran the headline "TRUSTEES TO END GREEK SYSTEM 'AS WE KNOW IT'" in type size usually reserved for a declaration of war, many students thought it was the paper's annual joke issue. Only after a lot of buzzing on campus and a front-page story in TheBoston Globe did students fully realize that something big was in the works.

By the eve of Winter Carnival any sense that the Trustees wanted student input on how to improve residential and social life had spun uncontrollably into a debate about the Greek system. (With roughly half of students participating in fraternities or sororities and many others claiming to be "unaffiliated, but supportive," perhaps that was inevitable, even predictable.) A week after the broadsheet hit the Hinman boxes Trustees William King '63 and Kate Stith-Cabranes '73 returned to Hanover to join President Wright, Acting Dean of the College Dan Nelson '75, and 30 students in a Q & A broadcast on Dartmouth's cable television channel. The mood of the telecast was more in keeping with a Senate impeachment trial than a College function. Wright repeatedly apologized for the handling of the announcement and the ensuing media circus. Trustees King and Stith-Cabranes (lawyers both) found themselves grilled by students on such fine points as the meaning of the phrase "substantially coeducational." ("Does the term mean no single-sex houses?" the students wanted to know.) Attempting to turn the conversation away from a debate about the status quo, Stith challenged the audience, "Can't you think of something better?" But the evening failed to move beyond a standoff.

That's not surprising, says Scott Brown '78, dean of the Tucker Foundation and an expert on conflict management. "This type of situation generates a lot of emotion. It's almost always necessary to let a period of time pass before anyone can make progress in negotiation or dialogue. In this case, since there are clearly a lot of common interests—the mutual agreement to improve Dartmouth, the general agreement on the five principles, the common interest in improving social life as a whole—the emotions are likely to settle down sooner," says Brown. He sees the vague language of the principles as a plus for students.

"In the short run, ambiguity causes a lot of fear because of the tendency to interpret it in the worst possible way," Brown says. "Once emotions calm down, ambiguity will lead to flexibility." In time, he believes, students will meet Stith's challenge.

Alumni may find that reassuring, too—eventually. In the days following the announcement, though, hundreds of faxes and e-mails zipped around the alumni body and to various offices in the administration. Much of the mail was angry and much of it was fired off even before the senders received the official statement and letter from Dartmouth. Dave Cook '57, president of the Alumni Council, called this "the most controversial issue to hit the College since the e-mail era began."

Said Jim Wright, "There are 50,000 alumni out there. Obviously there are some who've been very upset the last few days..." When asked about alumni threats to stop giving money, Wright stated emphatically that the College wouldn't let those concerns dictate policy.

As the news of the announcement settled, the media coverage and much of the discussion shifted from Animal House toward the heart of the issue: what kinds of social and living structures are appropriate for college students in this day and age? A New York Times editorial applauded the initiative and called for leaders at other colleges to follow suit: "The Dartmouth trustees are steering in the right direction when they question the role of fraternities as a means of social organization."

"The new direction will ultimately help admissions," says admissions dean Karl Furstenberg. "Many prospective students turn away from Dartmouth because of general concerns about the social life here and particular apprehensions about the role of fraternities and sororities and alcohol on campus. The decision will be very reassuring to students, parents, and secondary school educators, which I think will, in the long run, increase the size and mix of Dartmouth's applicant pool."

According to Wright, changes won't happen overnight. He says, for example, that despite early misreporting in the national press, there probably will be a traditional rush next fall. By then, though, the Trustees hope to have outlined a framework for a profoundly changed social and residen rial system at Dartmouth. Depending on the scale of the plan—and the new facilities it will require—full implementation may take a decade or two. In the meantime, Nelson has organized a task force to solicit and collect ideas from students, parents, and members of the administration. Alumni (see box page 9) have been asked to do the same. Trustees hope to have a wide-ranging list of ideas by early summer.

Now that the discussion has officially, if uncomfortably, started, Wright's task is to convince students that he and the Trustees truly want their imput. "They have a chance," he insists, "to do something that very few students at any American college or university have had a chance to do: to participate fully in imagining what a significantly enhanced student life and residential system would be like and then working together to make it happen." For example, what kind of new dorm space do students want? Townhouses? Small residences? More "superclusters"? Freshman dorms? What kinds of dining facilities? Centralized at Thayer? Smaller dining halls around campus? What kinds of social spaces, especially since Webster Hall is no longer available?

The discussion on campus is beginning to shift. Students associated with the College's organic farm are already cultivating an idea clearly focused on the future: a sustainable living center.

Collis is one of the few College-sponsored social spaces.

Will houses still be called frats in the next century?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

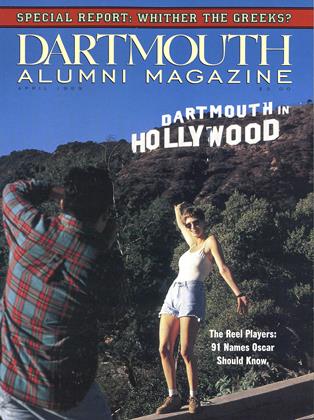

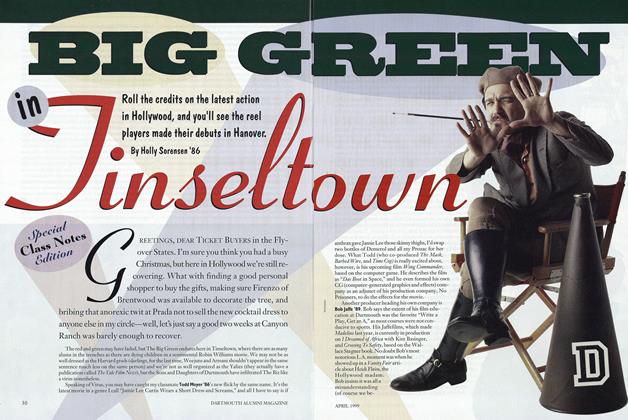

Cover StoryBig Green in Tinseltown

April 1999 By Holly Sorensen '86 -

Feature

FeatureProps, Wingers, And Keepers Of The Old School

April 1999 By Stuart Krohn -

Feature

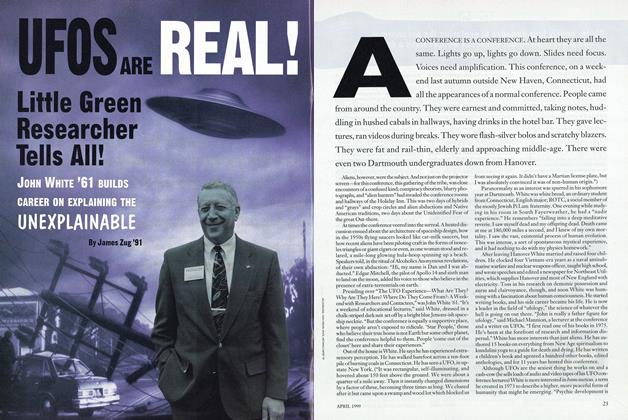

FeatureUFOs Are Real!

April 1999 By James Zug '91 -

Feature

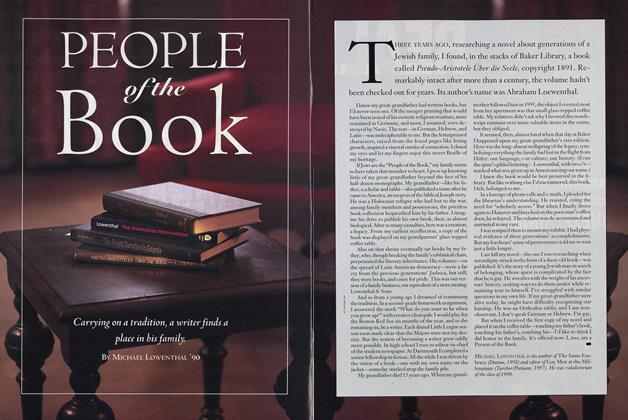

FeaturePeople of the Book

April 1999 By Michael Loventhal '90 -

Article

ArticleA Greek Tragedy

April 1999 By Kevin Goldman '99 -

Article

ArticleBuilding Community

April 1999 By James Wright

On the Hill

-

ON THE HILL

ON THE HILLCampus News and Notes

MARCH 2000 -

ON THE HILL

ON THE HILLHot Shots

MAY 2000 -

ON THE HILL

ON THE HILLDartmouth’s First Woman of Science

NOVEMBER 1999 By Celia Chen ’78, Ph. D. ’94 -

ON THE HILL

ON THE HILLThe Film Society Turns 50

JANUARY 2000 By Christopher Kelly ’96 -

On the Hill

On the HillCampus News and Notes

JUNE 2000 By Jen Whitcomb '00 -

ON THE HILL

ON THE HILLWinter Carnival 2000

April 2000 By Jennifer Whitcomb ’00