The press cried scandal. College officials called it an "unfortunate situation." Some students claimed it was a setup.

Call it what you like, but as allegations of widespread cheating rocked a computer science class in February, all agreed on one thing: the situation was a mess. Even

though the College dismissed all charges in mid-March, the visiting professor who had accused 78 students of cheating called the hearings "a whitewash."

While no students were punished, the College is left to ponder some tough questions: Is the honor principle clear? Do the procedures for handling suspected cases of cheating work? Does Dartmouth orient visiting professors adequately? And, in the still-unfolding realm of the electronic classroom, what actions do—or do not constitute cheating?

Professor Rex Dwyer's introductory computer science course (CS4) was plagued by bugs from the beginning. Dwyer, 41, a tenured associate professor at North Carolina State University, was spending part of a sabbatical as a visiting professor at Dartmouth. He expected to teach a course that usually draws approximately 110 students; the number swelled to 178 for reasons that remain unclear. The numbers fueled a rapid deterioration of classroom decorum, as some students reportedly talked aloud or read magazines during class. Others arrived late or left early. Some simply didn't show up.

Then came the fourth homework assignment: write programming code for the Pansy Game, an imagematching game similar to Concentration. In class, the professor demonstrated the game on his Web site ( www.cs.dartmouth.edu/~cs4/ pansies/game.html ) to familiarize students with how it is played. A few days later a student informed Dwyer that his Web site had been left unprotected and that students were downloading code from it.

Alarmed, Dwyer traced electronic connections from his Web site to campus computers that had accessed it. After students handed in their assignments, he compared answers and concluded that many students had copied each other's work.

The evidence convinced him that 78 students had violated the College's academic honor principle. Dwyer brought his suspicions to the attention of computer science chair Scot Drysdale, and from there to the Committee on Standards (COS), which handles serious student disciplinary matters.

Many students cried foul. Several reported that the course's teaching assistants had given them the solutions during help sessions. Other students reported that TAs were unable to accommodate them, so classmates had helped each other.

As stories about the incident started appearing in TheNew York Times, The BostonGlobe and other papers, Dwyer quit teaching and returned to North Carolina. Another professor took over the class.

After conducting hearings for the first 27 of the accused students the COS, chaired by Dean of the College James Larimore, decided that further hearings would be futile and dismissed all charges. In a March 10 letter to the Dartmouth community, Larimore and Dean of Faculty Edward Berger explained the situation. "The Committee concluded that some cheating did occur, but that the nature and the quality of the evidence, combined with the circumstances under which the course was conducted, made it impossible to distinguish between those responsible and those not responsible for violations," they wrote.

Dwyer disagrees. "The evidence I presented focused on obvious electronic exchange of written work, in clear violation of a clear policy included in the course syllabus," he told the Alumni Magazine.

"This is one of those Three Mile Island things," Berger says. "There were a number of small faux pas, none of which in themselves would have created a disastrous situation. A sequence of small faux pas occurring coincidentally led to a meltdown situation."

Repercussions from the CS 4 case are likely to linger. Many people in the College community feel that Dartmouth's reputation—if not that of students and of Dwyer—has been tarnished. Describing the case as "difficult and painful," the deans wrote in their letter that the time has come to begin "a new campus dialogue about academic integrity."

While Larimore says the honor principle is "fundamentally sound" as it pertains to the College's values, it is somewhat imprecise in at least one area relevant to the CS 4 case: what to do if you know a fellow student is cheating. "The principle requires that students take some form of action when they are aware that a violation has occurred," says Larimore. "But it does not specify what particular form that personal action might take." This and related subjects are likely to be discussed soon during a fireside chat at Collis that Larimore is planning as a result of the CS 4 investigation.

Dartmouth's academichonor principle can be read atdartmouth.edu/~npperde/acad-regs.shtml.

Cheat SheetStatistics show that cheating is a nationwide concern. In polls conducted on 26 college campuses during the last decade, more than 75 percent of students admitted to cheating. 57 percent of students attending schools with honor codes reported cheating. There is less chronic cheating at schools with honor codes: About 6 percent of students at schools with honor codes reported they cheated more than three times on tests. That figure jumped to 20 percent at schools without honor codes. According to a 1993 survey, 75 percent of students involved with Greek houses cheated at least once, compared with 61 percent of independents. Source: Center for Academic Integrity ( www.academicintegrity.org)

Bragging RitesBig Bang Marcelo Gleiser, professor of physics and astronomy and Appleton Professor of Natural Philosophy, has been named a fellow of the American Physical Society in recognition of his contributions to early universe cosmology. Gleiser joins a prestigious list of the society's fellows, which includes Nobel laureates. Gleiser is currently at work on a book about religious and scientific views of the end of the world.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

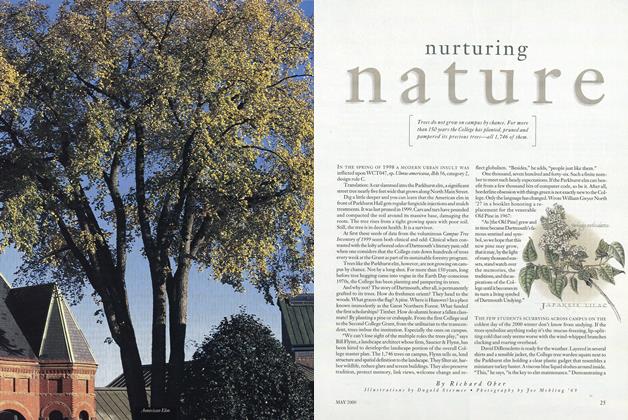

Cover StoryNurturing Nature

May 2000 By Richard Ober -

Feature

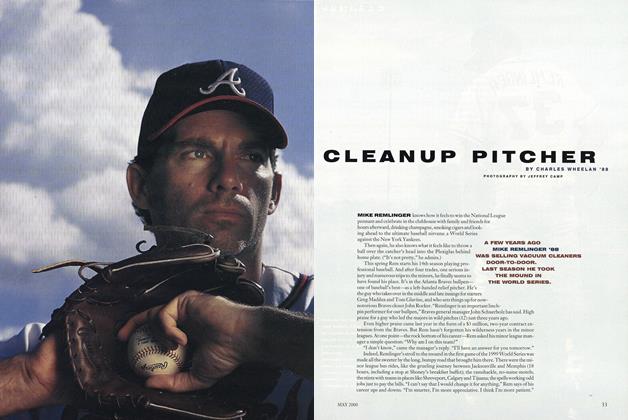

FeatureCleanup Pitcher

May 2000 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeatureLive From New York!

May 2000 By Jacques Steinberg ’88 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYThe Private Lives of Public People

May 2000 By Jennifer Avellino ’89 -

SYLLABUS

SYLLABUSScreening Reality

May 2000 By Kathleen Burge ’89 -

Article

ArticleThe Price of Excellence

May 2000 By President James Wright

ON THE HILL

-

ON THE HILL

ON THE HILLCampus News and Notes

MARCH 2000 -

ON THE HILL

ON THE HILLHot Shots

MAY 2000 -

ON THE HILL

ON THE HILLDartmouth’s First Woman of Science

NOVEMBER 1999 By Celia Chen ’78, Ph. D. ’94 -

ON THE HILL

ON THE HILLThe Film Society Turns 50

JANUARY 2000 By Christopher Kelly ’96 -

On the Hill

On the HillCampus News and Notes

JUNE 2000 By Jen Whitcomb '00 -

ON THE HILL

ON THE HILLWinter Carnival 2000

April 2000 By Jennifer Whitcomb ’00