"Your parents owned, not rented, your childhood home." I easily took a step forward towards the center of the circle. I was startled to see some of those beside me step back. We were standing in a wide open field, first-year Dartmouth students teetering on the threshold between casual acquaintances and friends, and suddenly the most taboo of subjects had been made central, inescapable, thrown out into the open for all to see the level of wealth, or poverty, with which we had grown up. "Your parents took time off from work to take you on family vacations." A step forward meant Disneyworld, the state park, or even the Bahamas a step back meant not. Apprehensively, I looked around. Only a few questions in and already the group barely resembled the perfect circle we had formed at the beginning.

As we answered a list of questions that even the best of friends would hesitate to ask, our vulnerability was palpable. For we were not even the best of friends, but a much more disparate group—33 freshmen selected to participate in the Leadership Discovery Program, a term-long series of workshops designed to build leadership skills. To this end, a large portion of the retreat was dedicated to getting to know the other people in the group, and perhaps in the process, better understanding some of the different elements that make up the Dartmouth community. But with each question, with each step that moved the group farther apart, I felt the tenuous thread unifying us pulled taut.

"You had household help on a regular basis growing up." It became obvious that the questions concerned only the sizes of our families' bank accounts, and I wanted to stop the game and redirect the line of questioning so that those who were constantly stepping backwards further and further away from the center could be pulled back in. Nothing was being asked of how much time our parents had spent with us, how much of themselves and overtime, they'd worked to give us what they did. After 20 or so questions, we were told to freeze and to take a long look at the people in the field around us. One group, clustered in the center of what had previously been our circle, looked out to the thick ring in the middle of the field where the majority of the group resided. A few people dotted the space between. Far away from where the circle had lain were those who had never taken a step forward. They stood apart, on the edges of the field. This, we were informed, was our community. There was no avoiding taking measure of how we stood in relation to one another, and that the measure wasn't equal.

As we comprehended what it meant to be where we were in the field, feelings of protectiveness and shock at the seemingly unfair nature of the exercise bubbled up in my throat. The person administering the exercise addressed our unasked questions of why. "It was now our job," she told us,"to unify the group without moving from where we stood." First we tried lying down and reaching for one another, but the field was too big and our group too spread out. Then someone had the idea of tying together our extra clothing and using the makeshift rope to connect everyone. The increasingly brisk wind was the last thing on our minds as we stripped off jackets, sweaters, and shoes whatever necessary to reach every person, no matter how far away they stood in the field. When the last person was lassoed in, we were congratulated on succeeding in bringing everyone together, differences and all.

Afterward, tears and support flowed freely as we talked about the intensity of the exercise, about the feelings of guilt and shame that it had brought up, and of the privilege, whether in the financial or emotional sense, that characterized each of our upbringings. An issue I would have before been loathe to broach gave me another reason to respect and another way to understand those around me.

MEETAAGRAWAL '01 is aWhitney Campbell intern at thismagazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureRoommates

September 1999 -

Interview

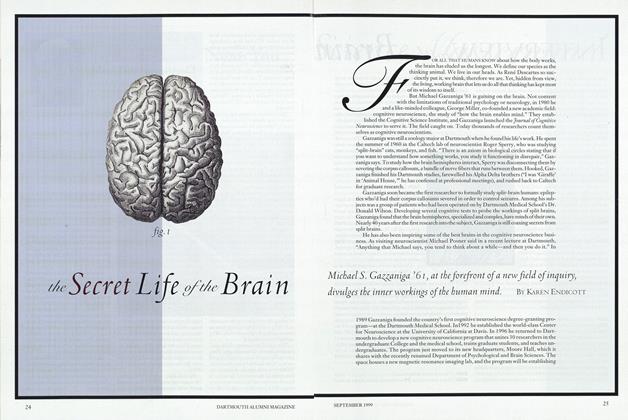

InterviewInterview with a Brain Science Mastermind

September 1999 By Karen Endicott -

Interview

InterviewDartmouth on the Brain: Green Research and Gray Matter

September 1999 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleComing to a Highway Near You

September 1999 By Professor Noel Perrin -

Class Notes

Class Notes1990

September 1999 By Jeanhee Kim -

Article

ArticleNightmares and Dreams

September 1999 By "Mom"