The characters we lived with, the bitter and the sweet.

Forget Lamaze class—ask for drugs." "Ignore the pediatrician—what does he know?" "Don't listen to other mothers.""Hey, lie about everything."

Twenty-two years later and I'm still advising Lisa, my freshman roommate. Protecting her long distance—from labor pains, Supermoms, and bossy pediatricians. I call California and command her to buy pacifiers, burn her babycare book, avoid playgroups. She listens, she laughs, she finishes my sentences. We continue conversations from 1975,1983,1994. We no longer share a bunk but, somehow, we are still connected.

Like most freshman roommates, we had different styles. Lisa came to Wheeler Hall with hammers, screwdrivers, ladders, and extension cords ready to renovate and rewire the dorm. I arrived in a swirl of hangers and overalls, dragging the plug from my electric blanket.

Lisa was quieter, "cooler," and more introspective than my high school crowd. She'd lived in Germany, played in a teenage rock band. She had an older, off-campus boyfriend who adored her. (This alone inspired awe.) Genetically slim, she ate Butterfingers between classes and whole pizzas before bed.

I lived a noisier, more frenetic life. I talked all the time and about everything. Choosing courses, gaining weight, finding boyfriends, finishing papers—nothing was too minor to obsess about. Each new semester, I agonized while Lisa simply stuck to her plan. She breezed through her engineering major, took master classes in piano, and became a track star without trying. For relaxation, she took courses in my major (English), tossing off "A" papers in-between computer projects.

Despite our differences, we grew together. On cold Sunday afternoons, when papers and homesickness loomed, we grabbed our coats and went to Peter Christian's. In a dark booth, we reassured ourselves about Dartmouth, loneliness, and college living. For four years, in the absence of our families, we took care of each other.

At 40, we contine to reassure one another about our choices: changing careers, having kids, doing the "suburban" thing that we'd sworn we'd never do. We talk less frequently than we used to, but our coast-to-coast calls never lag. Twenty-two years later, we're still talking, giggling, whispering frantically from the top to the bottom bunk.

Brendu Gross '79

At the end of freshman year I was assigned an abysmal housing number for the ORL lottery. My dream of a sophomore single dashed, I needed to figure out how to escape another year in the River. I found my loophole in Butterfield Hall the "substance-free" affinity house/dorm connected to Russell Sage, ironically juxtaposed to Fraternity Row. Butterfield had some great doubles. The catch was finding a roommate to share one with.

The list of applicants was almost completely teetotalers. I was familiar with only one name. Rob was a tall, skinny, bespectacled kid whom the entire'shmen class knew simply as "the guy who broke his leg on the D.O.C. trip and had to be carried down the mountain." How bad could he be? I asked myself.

We moved in together. He brought the stereo, I brought the fridge. Both of us would regret that sharing arrangement. I played my music with his volume dial turned twice as far as he had ever set it. He was appalled by what he found in my fridge.

Rob was a health nut. He ran the golf course and surrounding woods every day of his Dartmouth career. He was thin as thread and ate only healthy food (tofu dogs, wheat germ). You are what you eat, and Rob was granola through and through.

But he didn't fit that stereotype. In fact he didn't fit any stereotype. Puzzled friends would say to me, "So, what's his deal?" Over time I learned to reply, "Rob is so random—but it's cool."

And it was cool, in a weird way. The guy played electric guitar but had Coke-bottle glasses. He drove a red convertible but took organic chemistry for fan. I'd walk into the room some night after partying and find him using both of our computers (my LC III was the fastest Mac around) to run a vast database on his daily diet options. He was weird to the extent that you had to like him.

We've since lost touch, Butin a real world that categorizes people too easily, I sometimes miss him.

Kishan K. Putta '96

Not too long ago a song called "Sex and Candy" by Marcy Playground received heavy radio play. The chorus goes like this: "I smell sex and candy, yeah. Who's that lounging in my chair? Yeah. Who's that casting deep seated stares in my direction..." I read in Spin magazine that a band member wrote the song about his girlfriend's college roommate. He was basically trying to walk a mile in the shoes of a young woman whose first-year roommate has a boyfriend, a resident odor-emitting and space-polluting oaf whose constant presence is becoming a major chafe. This song should have been on the radio when I was a freshman living in a one-room cement-block double in the Choates. At least I would have had the solace of a theme song.

Patricia C. Howard '95

During sophomore year I lived in North Mass with a fellow named George Reid Andrews. His father was a minister down in Connecticut—and both of his parents were nudists. George was into physical fitness, and he had a whole philosophy about health and the body and the outdoors. He decided we should go out on Oak Hill in the spring and take off our clothes and ski. That was before they built the Oak Hill ski lift. The whole area was pretty heavily covered with pines and open spaces. About the only house out there belonged to Dean Strong. In those days, in our innocence, we hoped that we wouldn't run into a girl. That would have been awful. We ended up skiing that way more than once, but since it had to be reasonably warm and sunny and there had to be enough snow, it can't have been very many times. I wrote a story for the facko about it, and they said, "We'll print it if you give us your word that it's true," and I said "Yes, it's true." We didn't room together again, though I can't recall why.

William Rotch '57

A high-pitched sound was driving me crazy. I turned over and covered my head with my pillow. I sat up and tried to focus on the clock on top of the dresser. Three a.m. I got up slowly and shuffled over to the door that separated my small room from the larger room where my roommate slept. I put my ear to the door and listened. I'd never heard anyone snore like that. I gently pushed the door open. A movement at the far end of the room caught my eye. My roommate, in his jammies, was reading from a ream of sheet music and making noises with his mouth. My God, I thought to myself, he's lost hismind. And only a month into the first semester.

He looked up at me and smiled. "I'm taking a workshop on choral music and I thought I'd practice a bit," he said. "Some of these are quite hard."

I stood there looking at him for the longest time, not quite knowing what to say. Finally, I muttered, "OK," and went back into my room. I grabbed my guitar, plugged it in, and sat down in the chair by the window. I played for half an hour, until our neighbors knocked at the outer door and complained. My roommate and I went to sleep after that. We never talked about it. But the truth is, I played some of the best, most creative music of my life that night, at three in the morning.

Alvino-Mario Fantini-Cespedes '90

On a brisk Hanover morning in 1950 I climbed the stairs to 202 Streeter. A bright-eyed ectomorph from Pocatello, Idaho, stuck out his hand. "John Scoville," he said. I noticed that his acne was a bit worse than mine. We were roommates for four years.

The college paired like-kinds as roommates. John and I needed scholarship and work assistance at Dartmouth. Except for that, though, there was little commonality. John was focused from day one. He would be a civil engineer. He knew which courses he needed, which professors he preferred, which activities he wanted (skiing, outing club, the Christian union, others). I didn't.

In time we became good friends, but we had few friends in common. We shared very few classes. We shared a lot of ideas. He had great en- ergy. I think he red-lined around 10,000 rpm. He ran through those Hanover winters in a thin suede jacket he brought from Pocatello in 1950.

After graduation we met only once, briefly. We didn't stay in touch. I suppose we thought we were too busy. I imagined we'd catch up on each other's lives eventually, maybe at our 50th reunion. "Well,John,"I would say, "How are your declining years going?"

I went to Vietnam twice as a navy surgeon. I flew in many kinds of aircraft—in all kinds of weather. I saw a lot of people die, in war and later in my civilian chest surgery practice. The death of my old roommate in a plane crash near Dubrovnik bothers me more than most of the thousands of other deaths. What rankles is knowing the hubris of ordering John's plane up in weather unsuitable for flying. I've seen that sort of hubris frequently. It's difficult for me to come to terms with the senseless loss of a roommate and friend. I hope his family has managed to deal with the loss. I'll raise a glass for him at our 50th.

Richard M. Deaner, M.D. '54

My junior spring I suffered a bout of chicken pox—104° fever, a galaxy of blisters across my chest. I was quarantined in Dick's House for eight days. The first night, I awoke to a low moan that sounded like wind howling through mapletops. It felt as though it emanated from my skull. Then I heard a nurse coo, "Yes, John. All right, John." and I realized the noise had come from the room beside mine.

The next day and the next brought more haunting pleas for help. John's cries disturbed me, but they also forged a bond. Without words, he expressed all the fear and discomfort I was too proud to admit.

I felt I should know something of this neighbor, so I asked a nurse, who said my suitemate was none other than John Sloan Dickey, the revered former president of Dartmouth. Felled by a series of strokes, he now lived permanently in this sickly outpost. Because of how the beds were arranged, she said, John's head and mine were only inches apart.

I felt honored, and saddened, and inspired. This great man, whose rousing speeches I'd so often heard quoted, had been reduced to a speechless invalid. But fierce resolve and humanity came through even in his moans.

I'll never forget the feeling of sleeping next to him—separated by studs and dry- wall, but joined by the kinship of history.

Michael Lowenthal '90

After some time at Ripley Hall, I learned there is no such thing as living alone at Dartmouth. Dirty secrets and bad habits surrounded me, and having my own room didn't make much difference.

Thanks to Cornflake-thin walls, I knew more about the neighbor to my left than I did about myself. Kim was on the phone straight through fall till spring, save for die odd chemlab. Cousins, pals, the EBA's guy her phone bill came on a freight truck. Saturdays I woke up to the weekly fight with Mom about her grades. I knew her like a sister, but having not actually met her, I kept quiet My right-side neighbor, who loved ordering J. Crew sweaters at 2 a.m., had Bart Simpson provide the alert sound for incoming e-mail. I heard the term "Cowabunga!" at least eight times an hour. The noises that came during her boyfriend's visits were even more annoying. Doorslammer girl across the hall would tell them to shut up. Didn't work. I asked the girl to stop slamming. Didn't work either.

The guy below, whenever heavy metal wasn't blaring through his concert-tour speakers, played guitar himself. Mostly bad love songs, so I requested Metallica to make him stop. Upstairs was a quiet one. Not a peep for three weeks. Then at six o'clock one morning I woke up to relentless tapping directly above me. I walked up in my flannels and knocked. White socks and toaster-shiny black shoes the tap sort—struck me speechless. "Is anything wrong?" he asked. "Uhhhh," I stammered. "Do you know where I can get earplugs?"

I didn't have the heart to knock his art form. What are dormmates for?

Eastman's. $1.99.

Jennifer Wulff'96

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Interview

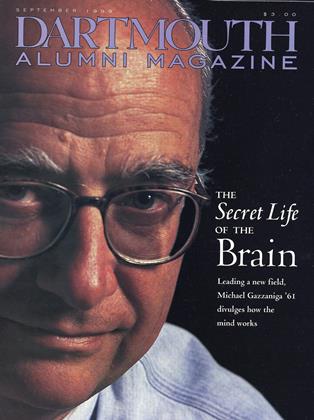

InterviewInterview with a Brain Science Mastermind

September 1999 By Karen Endicott -

Interview

InterviewDartmouth on the Brain: Green Research and Gray Matter

September 1999 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleComing to a Highway Near You

September 1999 By Professor Noel Perrin -

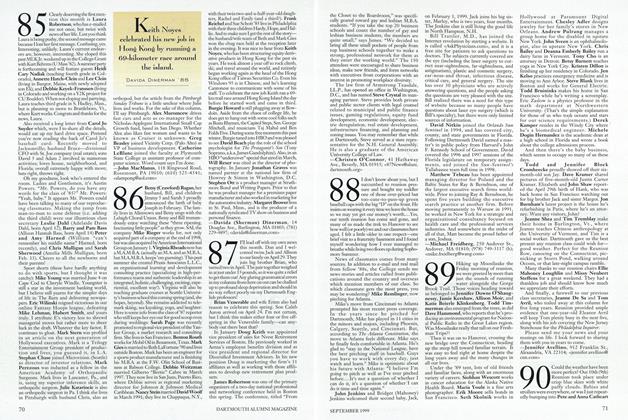

Class Notes

Class Notes1990

September 1999 By Jeanhee Kim -

Article

ArticleNightmares and Dreams

September 1999 By "Mom" -

Class Notes

Class Notes1998

September 1999 By Simone Swink

Features

-

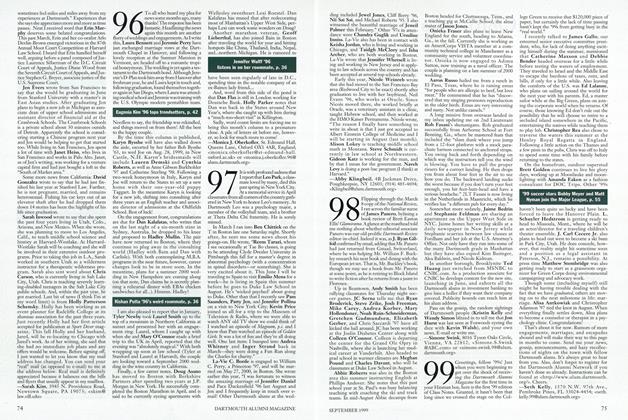

Feature

FeatureCOMPUTER ART

APRIL 1972 -

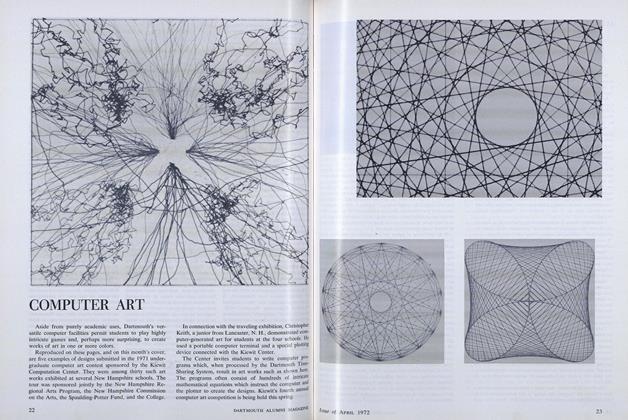

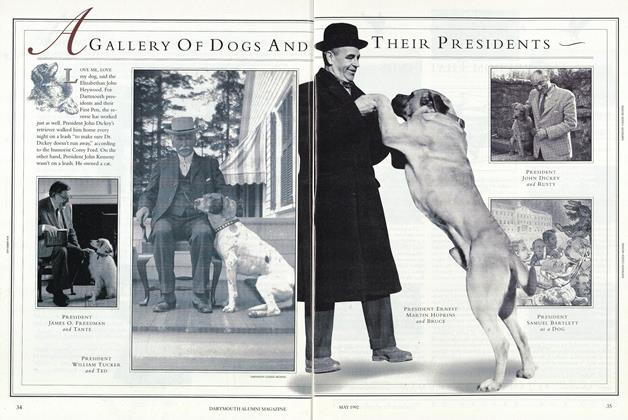

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Gallery Of Dogs And Their Presidents

MAY 1992 -

Feature

FeatureAlbert I. Dickerson '30 1908-1972

JULY 1972 By C.E.W. -

Cover Story

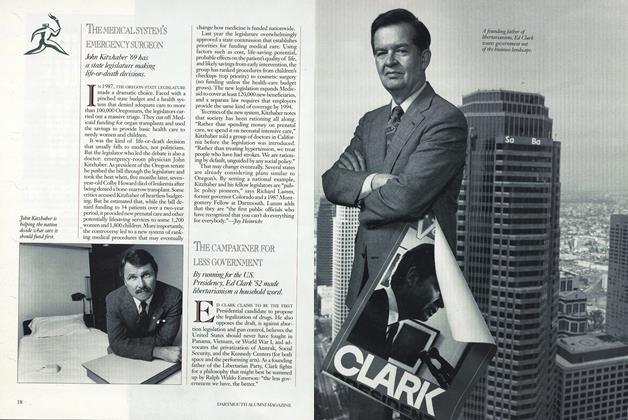

Cover StoryTHE MEDICAL SYSTEM’S EMERGENCY SURGEON

JUNE 1990 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureTHE CLASSICS

March 1962 By NORMAN A. DOENGES -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Awards Evening

October 1951 By THE HONORABLE SHERMAN ADAMS