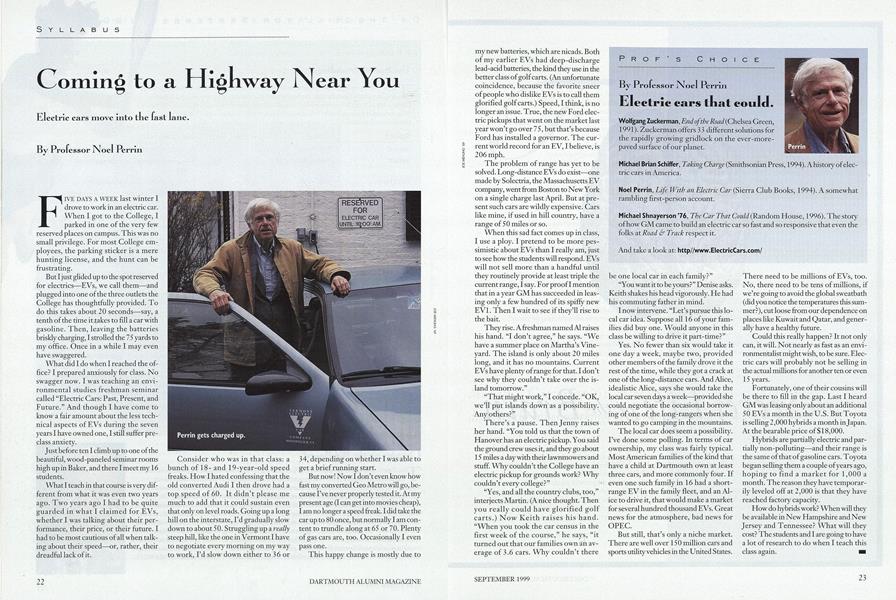

Electric cars move into the fast lane.

FIVE DAYS A WEEK last winter I drove to work in an electric car. When I got to the College, I parked in one of the very few reserved places on campus. This was no small privilege. For most College employees, the parking sticker is a mere hunting license, and the hunt can be frustrating.

But I just glided up to the spot reserved for electrics EVs, we call them and plugged into one of the three outlets the College has thoughtfully provided. To do this takes about 20 seconds say, a tenth of the time it takes to fill a car with gasoline. Then, leaving the batteries briskly charging, I strolled the 75 yards to my office. Once in a while I may even have swaggered.

What did I do when I reached the office? I prepared anxiously for class. No swagger now. I was teaching an environmental studies freshman seminar called "Electric Cars: Past, Present, and Future." And though I have come to know a fair amount about the less technical aspects of EVs during the seven years I have owned one, I still suffer preclass anxiety.

Just before ten I climb up to one of the beautiful, wood-paneled seminar rooms high up in Baker, and there I meet my 16 students.

What I teach in that course is very different from what it was even two years ago. Two years ago I had to be quite guarded in what I claimed for EVs, whether I was talking about their performance, their price, or their future. I had to be most cautious of all when talking about their speed or, rather, their dreadful lack of it.

Consider who was in that class: a bunch of 18- and 19-year-old speed freaks. How I hated confessing that the old converted Audi I then drove had a top speed of 60. It didn't please me much to add that it could sustain even that only on level roads. Going up a long hill on the interstate, I'd gradually slow down to about 50. Struggling up a really steep hill, like the one in Vermont I have to negotiate every morning on my way to work, I'd slow down either to 36 or 34, depending on whether I was able to get a brief running start.

But now! Now I don't even know how fast my converted Geo Metro will go, because I've never properly tested it. At my present age (I can get into movies cheap), I am no longer a speed freak. I did take the car up to 80 once, but normally I am content to trundle along at 65 or 70. Plenty of gas cars are, too. Occasionally I even pass one.

This happy change is mostly due to my new batteries, which are nicads. Both of my earlier EVs had deep-discharge lead-acid batteries, the kind they use in the better class of golf carts. (An unfortunate coincidence, because the favorite sneer of people who dislike EVs is to call them glorified golf carts.) Speed, I think, is no longer an issue. True, the new Ford electric pickups that went on the market last year won't go over 75, but that's because Ford has installed a governor. The current world record for an EV, I believe, is 206 mph.

The problem of range has yet to be solved. Long-distance EVs do exist one made by Solectria, the Massachusetts EV company, went from Boston to New York on a single charge last April. But at present such cars are wildly expensive. Cars like mine, if used in hill country, have a range of 50 miles or so.

When this sad fact comes up in class, I use a ploy. I pretend to be more pessimistic about EVs than I really am, just to see how the students will respond. EVs will not sell more than a handful until they routinely provide at least triple the current range, I say. For proof I mention that in a year GM has succeeded in leasing only a few hundred of its spiffy new EV1. Then I wait to see if they'll rise to the bait.

They rise. A freshman named Al raises his hand. "I don't agree," he says. "We have a summer place on Martha's Vineyard. The island is only about 20 miles long, and it has no mountains. Current EVs have plenty of range for that. I don't see why they couldn't take over the island tomorrow."

"That might work," I concede. "OK, we'll put islands down as a possibility. Any others?"

There's a pause. Then Jenny raises her hand. "You told us that the town of Hanover has an electric pickup. You said the ground crew uses it, and they go about 15 miles a day with their lawnmowers and stuff. Why couldn't the College have an electric pickup for grounds work? Why couldn't every college?"

"Yes, and all the country clubs, too," interjects Martin. (A nice thought. Then you really could have glorified golf carts.) Now Keith raises his hand. "When you took the car census in the first week of the course," he says, "it turned out that our families own an average of 3.6 cars. Why couldn't there be one local car in each family?"

"You want it to be yours?" Denise asks. Keith shakes his head vigorously. He had his commuting father in mind.

I now intervene. "Let's pursue this local car idea. Suppose all 16 of your families did buy one. Would anyone in this class be willing to drive it part-time?"

Yes. No fewer than six would take it one day a week, maybe two, provided other members of the family drove it the rest of the time, while they got a crack at one of the long-distance cars. And Alice, idealistic Alice, says she would take the local car seven days a week—provided she could negotiate the occasional borrowing of one of the long rangers when she wanted to go camping in the mountains.

The local car does seem a possibility. I've done some polling. In terms of car ownership, my class was fairly typical. Most American families of the kind that have a child at Dartmouth own at least three cars, and more commonly four. If even one such family in 16 had a shortrange EV in the family fleet, and an Alice to drive it, that would make a market for several hundred thousand EVs. Great news for the atmosphere, bad news for OPEC.

But still, that's only a niche market. There are well over 150 million cars and sports utility vehicles in the United States. There need to be millions of EVs, too. No, there need to be tens of millions, if we're going to avoid the global sweatbath (did you notice the temperatures this summer?), cut loose from our dependence on places like Kuwait and Qatar, and generally have a healthy future.

Could this really happen? It not only can, it will. Not nearly as fast as an environmentalist might wish, to be sure. Electric cars will probably not be selling in the actual millions for another ten or even 15 years.

Fortunately, one of their cousins will be there to fill in the gap. Last I heard GM was leasing only about an additional 50 EVs a month in the U.S. But Toyota is selling 2,000 hybrids a month in Japan. At the bearable price of $18,000.

Hybrids are partially electric and partially non-polluting and their range is the same of that of gasoline cars. Toyota began selling them a couple of years ago, hoping to find a market for 1,000 a month. The reason they have temporarily leveled off at 2,000 is that they have reached factory capacity.

How do hybrids work? When will they be available in New Hampshire and New Jersey and Tennessee? What will they cost? The students and I are going to have a lot of research to do when I teach this class again.

Perrin gets charged up.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureRoommates

September 1999 -

Interview

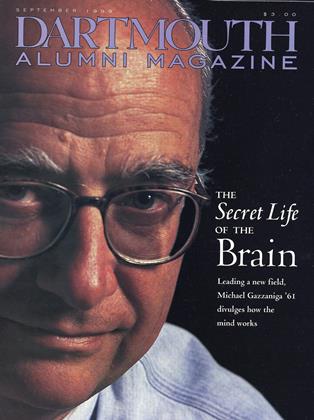

InterviewInterview with a Brain Science Mastermind

September 1999 By Karen Endicott -

Interview

InterviewDartmouth on the Brain: Green Research and Gray Matter

September 1999 By Karen Endicott -

Class Notes

Class Notes1990

September 1999 By Jeanhee Kim -

Article

ArticleNightmares and Dreams

September 1999 By "Mom" -

Class Notes

Class Notes1998

September 1999 By Simone Swink