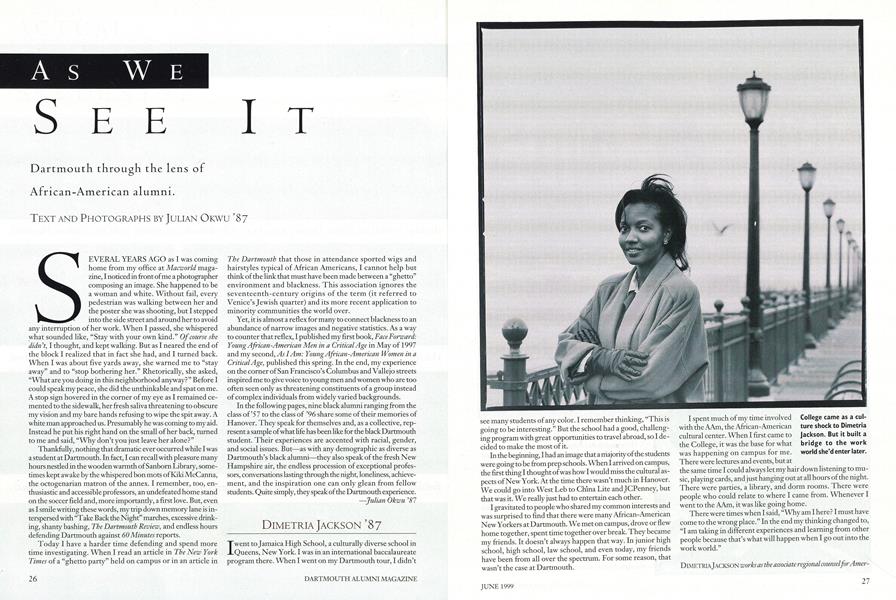

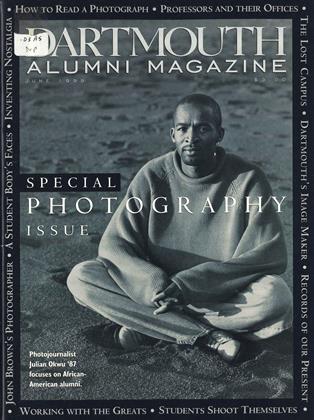

Dartmouth through the lens of African-American alumni.

SEVERAL YEARS AGO as I was coming home from my office at Macworld magazine, noticed in front of me a photographer composing an image. She happened to be a woman and white. Without fail, every pedestrian was walking between her and the poster she was shooting, but I stepped into the side street and around her to avoid any interruption of her work. When I passed, she whispered what sounded like, "Stay with your own kind." Of course shedidn't, I thought, and kept walking. But as I neared the end of the block I realized that in fact she had, and I turned back. When I was about five yards away, she warned me to "stay away" and to "stop bothering her." Rhetorically, she asked, "What are you doing in this neighborhood anyway?" Before I could speak my peace, she did the unthinkable and spat on me. A stop sign hovered in the corner of my eye as I remained cemented to the sidewalk, her fresh saliva threatening to obscure my vision and my bare hands refusing to wipe the spit away. A white man approached us. Presumably he was coming to my aid. Instead he put his right hand on the small of her back, turned to me and said, "Why don't you just leave her alone? "

Thankfully, nothing that dramatic ever occurred while I was a student at Dartmouth. In fact, I can recall with pleasure manyhours nestled in the wooden warmth of Sanborn Library, sometimes kept awake by the whispered bon mots of Kiki McCanna, the octogenarian matron of the annex. I remember, too, enthusiastic and accessible professors, an undefeated home stand on the soccer field and, more importantly, a first love. But, even as I smile writing these words, my trip down memory lane is interspersed with "Take Back the Night" marches, excessive drinking, shanty bashing, The Dartmouth Review, and endless hours defending Dartmouth against 60 Minutes reports.

Today I have a harder time defending and spend more time investigating. When I read an article in The New YorkTimes of a "ghetto party" held on campus or in an article in The Dartmouth that those in attendance sported wigs and hairstyles typical of African Americans, I cannot help but think of the link that must have been made between a "ghetto" environment and blackness. This association ignores the seventeenth-century origins of the term (it referred to Venice's Jewish quarter) and its more recent application to minority communities the world over.

Yet, it is almost a reflex for many to connect blackness to an abundance of narrow images and negative statistics. As a way to counter that reflex, I published my first book, Face Forward:Young African-American Men in a Critical Age in May of 1997 and my second, As I Am: Young African-American Women in aCritical Age, published this spring. In the end, my experience on the corner of San Francisco's Columbus and Vallejo streets inspired me to give voice to young men and women who are too often seen only as threatening constituents of a group instead of complex individuals from widely varied backgrounds.

In the following pages, nine black alumni ranging from the class of's7 to the class of '96 share some of their memories of Hanover. They speak for themselves and, as a collective, represent . 0a sample of what life has been like for the black Dartmouth student. Their experiences are accented with racial, gender, and social issues. But—as with any demographic as diverse as Dartmouth's black alumni—they also speak of the fresh New Hampshire air, the endless procession of exceptional professors, conversations lasting through the night, loneliness, achievement, and the inspiration one can only glean from fellow students. Quite simply, they speak of the Dartmouth experience.

DIMETRIA JACKSON '87

I went to Jamaica High School, a culturally diverse school in Queens, New York. I was in an international baccalaureate program there. When I went on my Dartmouth tour, I didn't see many students of any color. I remember thinking, "This is going to be interesting." But the school had a good, challenging program with great opportunities to travel abroad, so I decided to make the most of it.

In the beginning, I had an image that a majority of the students were going to be from prep schools. When I arrived on campus, the first thing I thought of was how I would miss the cultural aspects of New York. At the time there wasn't much in Hanover. We could go into West Leb to China Lite and JCPenney, but that was it. We really just had to entertain each other.

I gravitated to people who shared my common interests and was surprised to find that there were many African-American New Yorkers at Dartmouth. We met on campus, drove or flew home together, spent time together over break. They became my friends. It doesn't always happen that way. In junior high school, high school, law school, and even today, my friends have been from all over the spectrum. For some reason, that wasn't the case at Dartmouth.

I spent much of my time involved with the AAm, the African-American cultural center. When I first came to the College, it was the base for what was happening on campus for me. There were lectures and events, but at the same time I could always let my hair down listening to music, playing cards, and just hanging out at all hours of the night. There were parties, a library, and dorm rooms. There were people who could relate to where I came from. Whenever I went to the AAm, it was like going home.

There were times when I said, "Why am I here? I must have come to the wrong place." In the end my thinking changed to, "I am taking in different experiences and learning from other people because that's what will happen when I go out into the work world."

DIMETRIA jACKSON works as the associate regional counsel for American Title Insurance Co. She remains active in College affairs as the SanFrancisco Bay Area regional coordinator of the Black Alumni at Dartmouth Association. She lives in San Francisco, California.

GARVEY CLARKE '57

When I graduated from high school in '53 there was a movement in the country to get rid of institutions like segregation. I remember catching a train in New York to go to my wedding in Tallahassee in '61. When I boarded I was allowed to sit anywhere I wanted. When we got into Jacksonville, I asked a steward where the train connecting to Tallahassee would be, and he told me to follow him. The next thing I realized I was sitting in a car with nothing but black people. He was good enough to keep me from getting in trouble. I probably would have sat anywhere.

At the time there was a level of segregation in place at Dartmouth, as well. The College in those days would only allow black students to room with other black people. As a black student it was either that or you would have a single. If you decided on your own that you wanted to room with a white classmate you got along with, then there was no problem. But the College wouldn't do that on its own.

I knew I was as good a student at Dartmouth as anybody else. I believe the three other blacks in my class—my roommate Tom Young, Gene Booth, and Warner Traynham—also felt the same way. My parents had positively brainwashed me to believe that I could compete against anybody, regardless of their skin color. I didn't even realize until I got to Dartmouth that my family was considered poor.

I wanted the ultimate college experience and, for me, coming out of Bedford Stuyvesant in New York, getting out of the city and living on campus 24 hours a day was the primary goal to that end. I felt good being in a place where the air was fresh and the scenery so beautiful. The only tiling I didn't feel good about was all those science courses I had to take as a premed.

Throughout my four years, I never felt any inhibitions for myself. I could be as good as my talent allowed me to be. We were able to function, socialize, and compete with anybody else who was a student there. We did realize, however, that in those days it was still not an ideal community. It became a more positive place when the College held a referendum to ban any fraternities that were not racially integrated. Although there were no more than 21 blacks on campus, the student body voted the right way. They voted to ban those fraternities. It showed me that our colleagues in the majority were backing us and they wanted Dartmouth to be an even better place than it was. As great as the Dartmouth campus became, I still spent a lot of my time in Boston. It was sort of a secondary campus for me on the weekends. The schools there had many blacks so it became a social outlet for me. I dated women from Smith, Wellesley, or Mount Holyoke, women I'd found out about through other black students in the surrounding area. We were obligated to find out who the sisters were in those places and then come back and share the information with our Dartmouth classmates. It was almost like we knew all the blacks who went to school in New England. In retrospect, I guess it was my first experience in networking.

In 1972 GARVEY CLARKE chaired, the steering committee that coordinated the College'sfirst gathering of black alumni. An outgrowthof that event was the formation of BADA (Black Alumni at Dartmouth Association). It may he why many black alumni often refer toClarke as "Mr. Dartmouth." A former lawyer for the NationalBroadcasting Co. and current president of the Leadership Educationand Development Program, he lives in New York.

KEITH BOYKIN '87

One evening when I was in high school, I was watching Nightline, and a professor named Bill Cook and somebody from The Dartmouth Review were arguing about some racial issue. As I watched, I knew Dartmouth was the place I wanted to be. It seemed as though there was a lot of controversy and activism there, and I wanted to help stir up the trouble. In truth, I was intrigued by the idea of fighting against conservatives.

I roomed in New Hampshire Hall with two conservative white males, and we argued about everything—the school song, the Indian symbol—from the day we met until the end of our year together. Often, we would argue for no reason except to be argumentative. I loved the arguments I had with people. I learned so much just from sitting up at night talking to my zaroommates, friends, even enemies. Some of my most profound moments occurred in dorm rooms or, later, in Casque & Gauntlet talking to people by the fire in the living room while someone played the piano. Dartmouth was small enough that you could build those kinds of relationships.

But the whole time I was on campus, interestingly enough, I really wasn't an activist. Even with the arguments an[phed debates, I was still not an activist. In fact, I did all the traditional, establishment type of things, like being a tour guide, running track, and working as the editor of The Danmouth. It was a life totally at odds with what I had expected to do in college. I must say, however, that as editor of the newspaper in '86,1 was at ground zero for what was one of the most 32tumultuous years at the College since coeducation began in 1972.1 happened to be coming home at three in the morning from the newspaper and saw the campus police on the Green. I found out that the shanties [erected by students from the Dartmouth Community for Divestment to illustrate the plight of poor South Africans living in shanty towns] had been attacked by a group of right-wing people associated with The Review who called themselves The Dartmouth Community to Beautify the Green. I rushed back to the newspaper offices to stop the presses and get the story into the paper for the next day. A succession of campuswide protests followed. A couple of days after the bashing, about 200 to 300 students marched into Parkhurst and took over the president's office. Another group of students had taken over the bell tower in Baker. When President McLaughlin came back from a fundraising business trip in Florida, he announced a moratorium on classes so the community could deal with what was happening. I was there covering all of it, and it was wonderful and amazing to witness.

The energy of that time taught me a lot and gave me a unique perspective. I was an outsider and not quite as engrossed in some of the politically correct politics as others may have been. As a reporter—an observer I remember going to one or two protest organizational meetings and noting how the groups had tried to make decisions by consensus. With 50 or 60 people in the room it was outrageous. I shared their progressive orientation but I didn't share all of their methodology. I had been working in the establishment world of the newspaper where there was a clear linear line of authority. Even though I don't really believe in the status quo because I think it's oppressive, I recognize that I am very much a part of it by virtue of my experiences and background. I know now that my experiences offered me the best of both worlds. I've tried, at least, to use those experiences to help bring light to people who might not otherwise have it.

KEITH BOYKIN went from Dartmouth to Harvard Law School toseveral positions in the Clinton White House—"not indicative ofsomeone skeptical of traditional paths to success," he notes. But withtwo books about black gays and lesbians, One More River to Cross: Black and Gay in America and Respecting the Sonl, a positionas executive director with the National Black Lesbian Gay Leadership Forum, and ayear as an Atlanta public school teacher, Boykinhas never really abandoned his activist ideals. He lives as a fulltime writer in Washington, D. C.

JULIAN O'CONNER '96

Part of the reason I decided to go to Dartmouth was because it was so different from the Bronx. As soon as I arrived on campus and measured what I had achieved to get in against where I had come from, I knew I was already ahead. In the ghetto, you are exposed to more bad options than you are to good. A kid growing up in Beverly Hills would have a harder time learning how to be a drug dealer than a kid from the Bronx would. In my neighborhood that was the trade you learned first. I knew people who were a lot smarter than me but who had decided to make their money on the street. Some had families to support, and others thought that if their own parents couldn't support the family, then someone had to.

What I found missing at Dartmouth, though, was a sense of mentorship for African-American students. Although there were black faculty members on campus, the only contact I had with them was in their classes. There was no one to say, "Well, Julian, I notice you haven't been doing well in your studies. What's going on?" It was at a point where the only support we received was from each other.

Relations that black students sometimes had with white students didn't really help that feeling of isolation. One of the things that white students would always say was, "all black students sit together at lunch." I used to point out that all the fraternity boys sat together at lunch, as well. Those students who complained never made the effort to come to our tables. It always seemed necessary for the black students to extend ourselves. I guess they saw us as having to do that to get ahead in society.

At Dartmouth I received a Rockefeller Brothers Fund scholarship for work in education administration. I knew I could go to New York and work in the inner city, but the only way I would truly learn was to pull myself out of my comfort zone. Instead, I went to a predominantly white prison in Vermont to teach inmates to read and write. That experience showed me a reality of American life that I thought didn't exist: that there were people who have it just as bad as the people in the inner city. When I came to college, I had moved out of the comfort zone of my neighborhood in New York. At Dartmouth I moved out of that comfort zone again. It was a time when I was truly learning.

JULIAN O'CONNER is working on a master's degree in sociology atStanford University in Palo Alto, California.

PAMELA JOYNER LOVE '79 GARY LOVE '76

Gary: The first time I saw Dartmouth I was scared to death. In fact, I didn't buy any Dartmouth paraphernalia the first three months I was there because I wasn't sure it was the place for me. Even though I knew I could compete with the other students, one is never sure what the playing field is going to look like until one actually starts to play the game. Just as I wasn't one of those well-rounded Dartmouth kids—33 classes and 22 were math or economics—I also didn't circulate throughout the entire Dartmouth community. My experience was totally black. I now consider that type of college existence as both a plus and minus.

It was a plus because—even though the institution, professors, and administrators were supportive—it created an infrastructure for me to survive in Hanover. But I saw it as a minus when I received my diploma, looked out into the audience, and felt as if I didn't know anybody there. When I went into the real world I didn't have many classmates who could be supportive. I was like a threelegged table that desperately missed my fourth leg.

Pamela: I don't think either one of us romanticizes the Dartmouth experience. In fact, looking back on my time in Hanover, I see there wasn't a natural or readymade place for me when I enrolled. There was a place though. I just had to spend some time and find it.

In four years I never went into a fraternity. As a black student and as a woman, I did not feel welcome there. It is fair to say that there was some amount of self-segregation going on, but that was not what was driving the isolation of the black students. What drove it is that the broader institutions didn't seem to be welcoming to us.

With that said, learning to navigate the entire community was the single most productive thing I took from Dartmouth. At the time I enrolled I was considered a little unusual. And, certainly when I went to Wall Street after graduation, I was not typical there either. When I came to the investment management side of the business, again I was not the prototype. The training ground for me navigating in something other than my natural comfort ground was the Dartmouth campus.

Now, when we recruit potential students who are of color, we tell them they must navigate the whole community. Otherwise they will really cheat themselves out of the essence of the Dartmouth experience.

Gary: That understanding of college life helps to broaden your expectations. It's the students on campus who give you the vision of what is possible to achieve.

PAMELA JOYNER LOVE graduated from Harvard, Business School andnow works for Bowman Capital Management, LLC. After Northwestern Business School and ten years in investment banking as apartner at Kidder Peabody, GARY LOVE recently sold his company,Hanover Systems. The couple lives in San Francisco, California.

LORNA HILL '73

I was an exchange student from Wellesley and submitted my application for enrollment to the College right before the Trustees voted on coeducation. After their decision to go coed, and some controversy over my application, John Kemeny stepped in. He facilitated my becoming the first woman to be accepted to Dartmouth.

Being a woman was a far bigger deal for me than being African American. What made me comfortable on campus as a full-time student was that Dartmouth didn't know what to do with females. Instead of trying to acculturate the 17 of us who were there, they allowed us to be self-determining. They even looked to us for advice. One time, I went to eat dinner and the fellas were having food fights and eating contests in the dining hall. It was nauseating. The College hadn't realized some women entering as new students would find some of this pretty difficult to take. Sol went over to the dean's office and told him I couldn't eat in there and I needed my scholarship food allowance to eat in town. At first he said no, but I continued to make my point and was eventually allowed to eat off campus.

Throughout my four years most of my friends were fellas but there was only so much I could do with them since they had manstuff to do and couldn't always include me. When I had been at Wellesley, my friends were concerned about my plans to pursue an exchange in Hanover because Dartmouth men were then called "The Dartmouth Wolves." But I knew that the men—except for when they were being hazed—didn't bay at the moon. They were really normal people.

It may be hard to believe, but I really felt like I belonged at Dartmouth. That was in large part due to the exceptional professors on campus. To this day, I credit them with my love of scholarship. You didn't have to be in Peter Bien's class to hear him discuss Kazantzakis's The Last Temptation of Christ. You didn't have to be in Professor West's class to hear him give his famous lectures on cowboys and Indians. John Rassias was my mentor even though I never took French. Even though I was not a theater student and had not taken any theater classes, I performed in The Blacks and Ti-Jean and HisBrothers under Errol Hill's direction. By treating me like a professional, Professor Hill gave me the sense that I was a professional actress. I was born for the stage—I just needed someone to recognize and encourage it. Professor Hill did just that. I'm not sure I would be doing theater today if it had not been for Dartmouth.

LORNA HILL created a multiethnic theater group 20 years ago,Ujima Company Inc. Today she is the company's artistic executive director and lives in Buffalo, New York.

RICKI FAIRLEY-BROWN '78

When it came to choosing a college, my father told me I could go to any college I wanted to but that he was only going to pay for an Ivy League school. That narrowed my choices down to eight. He often describes me and my sister as his "two daughters—one is my smart one who went to Dartmouth and the other is my not-so-smart one who went to Princeton." I was in the third class of women at Dartmouth, and the seniors were still overwhelmingly male. Many of them didn't recognize the women on campus until Friday night. Needless to say, it was quite a transition for me to go from an all-girls high school to a college where I was the only woman in some of my classes. But even today I have the best memories of that time. There was something about Dartmouth that transformed jyme, made me believe I was going to build a better life for myself. There was something magic about the campus. When I interact with people who went to other colleges, I find that they don't feel the same connection to their institutions or to the people they met there. I think that's because, at Dartmouth, we only had each other.

On my first day at school I met a classmate named Victoria Stewart. My dad and mom were getting ready to drop me off, and I was crying because I had never been away from home for any significant length of time. My father spotted Vicky walking down the street. He pulled over, rolled down the window, and said, "Get in the car, little girl." She had never been out of her hometown of Chattanooga, Tennessee, before. To this day she doesn't know why she got in the car with a bunch of strangers, but she did. When she was seated next to me in the back, my father turned to her and said, "This is my daughter Ricki. What's your name?" She told him, and then he said, "Good. Be her friend. Now both of You get out." He drove us to the light and said, "See ya." Twenty-four years later she is still my best friend.

RLCKL FAIRLEY-BROWN, who attended high school at the Academy of the Holy Cross in Kensington, Maryland, had some exposure to Dartmouth through her father, Dick Fairley '55. As thedirector of marketing works at Coca-Cola USA she has overseen amajor increase in Coca-Cola's marketing programs. She lives inAlpharetta, Georgia.

WALLACE FORD '70

While I was at Dartmouth we had black Rhodes Scholars and senior fellows, proving that we were participating in the academic aspect of the school. But we also thought it was important to get involved in black student recruitment. With that in mind, a number of black Dartmouth students took time during vacations to recruit potential black applicants. I think 16 or 18 blacks came in as a part of the class of '70. By the time I was a senior, there had been a national change in the way black and hite people were interacting, and maybe 40 or 50 black students were expected for the next year.

One of the first collective experiences the black students in my class shared was when George Wallace [at the time, the governor of Alabama] came to campus in '66. The four girls had just been murdered in the bomb blast in Birmingham, and Wallace represented, to us, the personification of evilso we needed to do something. We held banners and booed throughout his speech to the point that he had to give up speaking.

Afterwards we followed him out of Webster Hall to his car and surrounded it. We rocked the car with him in it and were able to get the wheels to leave the ground. All the while, the event was being covered by the national news media. We ended up on CBSEvening News and in Time magazine, among others.

Even though our parents were not happy about the turmoil we had caused, it wasn't because they thought our motives were wrong. Hell, they had certainly suffered much more than we ever could in terms of daily confrontations and indignities. However, ever, they did think that we had lost our minds. They were saying, "Look, we sent you to Dartmouth to get an education, not to change the world. And certainly hot to change Dartmouth."

During my four years many other personalities came to the campus: LeßoiJones, Floyd McKissick with CORE, Alvin Alley, and even Sly and the Family Stone. Many of them provided energy and perspective for us, but they also provided some real insight for the white students who had never heard of them before. They revitalized us and gave meaning to the many of us who were giving of our time and of ourselves in the belief that we were doing something important.

Often, you don't realize the impact of the things you have said or done until much later. Dartmouth was an important time for me because many of us raised issues that no one else on campus wanted to talk about, and we learned a lot in the process. A classmate of mine recently e-mailed me with his disbelief that back then we really thought we were going to change the world. I told him that we did change the world. It's only that it still needs a little more changing.

After deciding against a Commencement address to the class of'70by Richard Nixon, the College allowed Wallace FORD to presenta speech as an "Equal Opportunity Speaker." During his 25th Reunion Ford ran into a classmate who still periodically reads thatspeech to his children. Wallace Ford is a partner in the corporate finance group ofK. Scholler law firm in New York City.

College came as a culture shock to DimetriaJackson. But it built abridge to the workworld she'd enter later.

Though Hanover in thefifties was far from ideal,Garvey Clarke found "Icould be as good as mytalent allowed me to be."

Beginning at Dartmouth, Keith Boykin has straddled two worlds: that of the activist and that of the establishment.

Julian O'Conner's education grew with discomfort. "What I found missing at Dartmouth was mentorship."

Students of color must navigate the entire College community for the broadest experience and vision, advise the Loves.

Wallace Ford looks back at Dartmouth in the late sixties and recalls aspirations springing from a tumultuous era.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

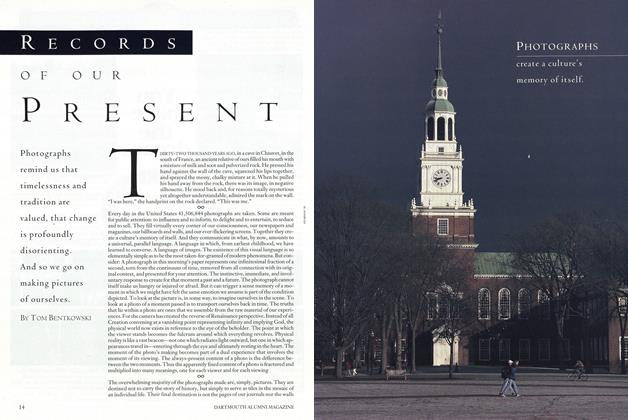

ArticleRecord of Our Present

June 1999 By Tom Bentkowski -

Article

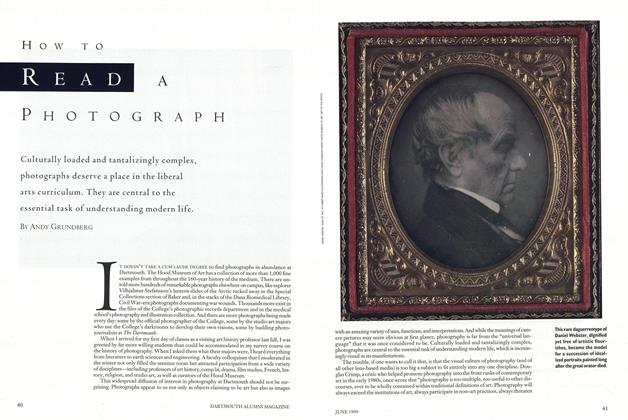

ArticleHow to Read a Photograph

June 1999 By Andy Grundberg -

Article

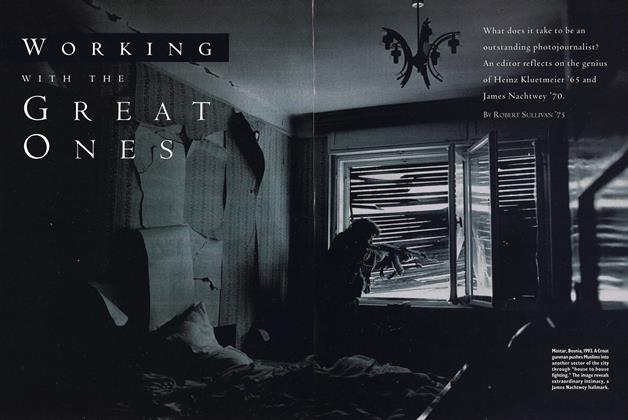

ArticleWorking with the Great Ones

June 1999 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Article

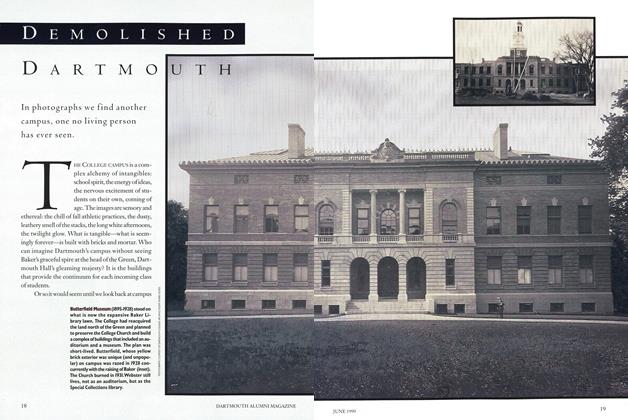

ArticleDemolished Dartmouth

June 1999 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1979

June 1999 By Jeffrey D. Boylan, R. James "Wazoo" Wasz -

Class Notes

Class Notes1982

June 1999 By Mark Soane, Rick Bercuvitz