Screening Reality

Documentary films show that the truth has always been of our own making. In Mark Decker’s Film Studies 30 class, students watch the evidence.

MAY 2000 Kathleen Burge ’89Documentary films show that the truth has always been of our own making. In Mark Decker’s Film Studies 30 class, students watch the evidence.

MAY 2000 Kathleen Burge ’89Documentary films show that the truth has always been of our own making. In Mark Decker's Film Studies 30 class, students watch the evidence.

It wasn't Psycho or The Blair WitchProject or even Jaws. In fact, the first horror movie hadn't yet been made. But when Louis Lumiere showed his film, innocuously called Arrival of a Trainin the Station (L'Arrivée d'un Train en Gare), spectators ran screaming from the theater. It was Paris in 1895, and people had rarely seen film, let alone a train speeding at them from the screen.

A century later, Professor Mark Decker shows the film at the beginning of his class "Films of Information and Persuasion." His students, bred on virtual reality, are underwhelmed. They can't comprehend why the film was terrifying. Decker tells them to imagine their reaction if he were to bring a hologram of their parents to class—a technical feat that he predicts will someday seem tame.

The disconnect between Dartmouth students and Lumière's audience, Decker says, illustrates some of the undying questions that film has provoked since its earliest days. "How do we read film? How do people see things for the very first time? " asks Decker. The questions are not simply academic for the professor, who lives in Santa Monica, California, most of the year and has made films ranging from his 1985 Time of Change: Confronting AIDS, one of the earliest documentaries about the disease, to a 1996 fictional feature film called Casa Hollywood. "There's always been a feeling that documentary gets at the truth," says Decker. "Well, what is the truth?"

prospector, Flaherty wanted to capture the life of Eskimos unspoiled by Western civilization—despite the fact that that way of life no longer existed. Although Eskimos no longer hunted walrus with harpoons, Flaherty convinced them to stage such a hunt for his film. The battle between the men and the walruses turned ugly, and some of the To get at answers, Decker takes his class through a film series that demonstrates just how misleading onscreen images can be. For example, they watch Robert Flaherty's famous documentary Nanook of the North, released in 1922. A former explorer and harpooned—but still living—walruses nearly pulled the hunters into the icy water. When some of the panicked men shouted to Flaherty to shoot the walruses with his rifle, he pretended not to understand their pleas and kept filming, he later admitted.

In Nanook Flaherty also ignored social and ethical issues, such as the influences and dangers of white people—the trading posts that brought in foods Eskimos weren't used to digesting, or diseases that they didn't have immunity against. Such oversights were not unique to Flaherty or his era. "These issues come up again and again and again," Decker says. "People don't necessarily put people in danger anymore physically. But we can put people in danger psychologically by asking them probing questions, by getting them to reveal things on camera that later may come back to haunt them."

While Flaherty was filming a romanticized version of the truth, one of his contemporaries was immersing himself in the everyday. The Russian socialist filmmaker Dziga Vertov saw himself as a reporter. His early films showed scenes of the 1917 Russian revolution, Lenin's funeral, the Moscow trolley returning to service. Vertov, his wife and his brother—he called them the Council of Three—saw their work as a superior alternative to the feature films of the day. "They were vehemently against fictional filmmaking. They felt it was another opiate for the masses," Decker says. Vertov thought people should confront realityand that the camera was the best way to show it to them.

At the same time, Vertov questioned "reality." In his 1929 film The Man With theMovie Camera, Vertov showed scenes of daily life in his country—a woman washing, men marching, trains, traffic, roofs. He also filmed his brother filming and his wife editing. He interspersed all those images with children watching a magician. "The message is this is like magic, and you should be as awed by this as little children are by a magician," Decker notes. "So he says, 'ls the reality my brother's film? Or me filming my brother? Or is the reality what my wife is creating in the editing room? Or is it the reality that you are giving to it, through your interpretation as a viewer?' "

Whereas Vertov tried to unmask films' layers of truth, wartime films in the United States tried to cover them up. In the 1930s and '40s the March of Time news reels provoked moviegoers by taking editorial positions and recreating events with actors. Government propaganda films exhorted women to take factory jobs to help the war effort. And when the soldiers returned after the war, the same films urged women to go home and leave their jobs for the men. Hollywood director Frank Capra made seven films in the Why We Fight series; viewing them became a mandatory part of military training.

The next major developments in documentaries, cinema verité and "direct cinema" of the 1960s, tried to capture ultimate truth, often by focusing on everyday lives of people. "Cinema verité tried to provoke reactions in its subjects through an interaction between the filmmakers and the subjects. Direct cinema believed the camera should be as unobtrusive as possible and merely record what was taking place around it, a true 'fly-on-the-wall' approach," Decker explains. "The theory was, the less you manipulated the subject matter in the filming and editing, the more chance you had of capturing 'the truth.'"

Such "truth" still has its flaws, however, for even if the direct technique tries not to distort what it sees, people often freeze in front of the camera. Decker raises the logical question: "How differently did people act when you had a camera in their faces from the way they acted 'normally' when you weren't filming them?"

Nonetheless, direct cinema broke new ground. One of the first direct-cinema films, called Primary, documented the 1960 Democratic presidential primary between John F. Kennedy and Hubert Humphrey. The filmmakers Richard Leacock and Robert Drew promised not to ask the candidates to do anything for the film. "They said, 'All we want is to follow them around,' " Decker says. "It was riveting because people had never had that intimate a view into politicians' lives." The professor has to remind students that Primary was filmed before the days of live television. "The trick is to get them to view the film with fresh eyes and experience it the way audiences did in 1960."

According to Decker, documentaries are still evolving. His own goal as a filmmaker is to create a fresh emotional impact, no easy task in a culture flooded with images. The way to do that, he believes, is through the time-honored tradition of seeking the truth. But as history shows, the truth has always been of our own making. Some contemporary filmmakers have been giving feature films the look and feel of documentaries, as Steven Spielberg did to great acclaim in Schindler's List and SavingPrivate Ryan. Then there are history bending docudramas like Oliver Stone's JFK. And there is greater variety to come. The Internet, with its Webcams and streaming videos, is opening a whole new chapter in documentaries. "It's akin to the early days of film," Decker says. "It's open to anyone with ideas and ambition."

Students observe how Lumière's train, Nanook of the North and World War II newsreels framed their own matters of fact.

KATHLEEN BURGE is a freelance writer. Shelives in Norwich, Vermont.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryNurturing Nature

May 2000 By Richard Ober -

Feature

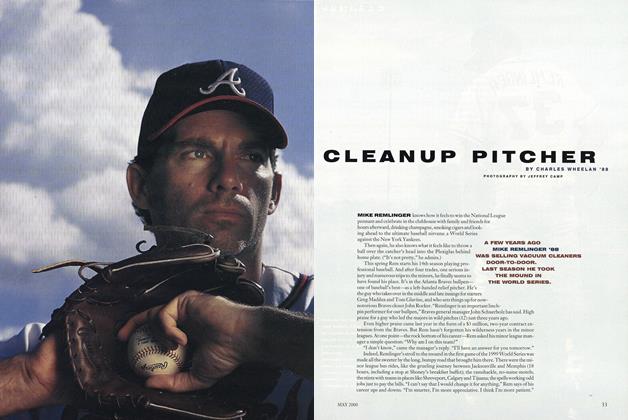

FeatureCleanup Pitcher

May 2000 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeatureLive From New York!

May 2000 By Jacques Steinberg ’88 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

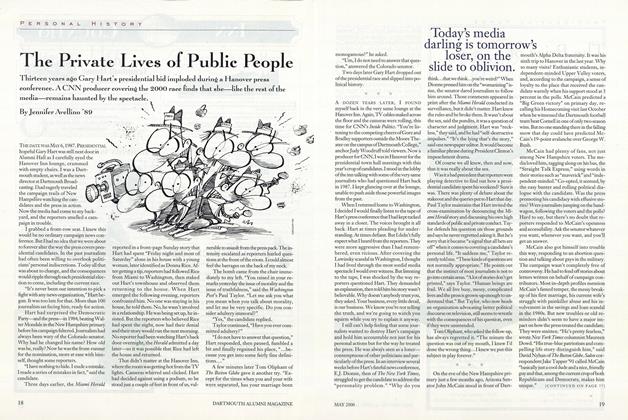

PERSONAL HISTORYThe Private Lives of Public People

May 2000 By Jennifer Avellino ’89 -

Article

ArticleThe Price of Excellence

May 2000 By President James Wright -

Article

ArticleYou Are Here

May 2000 By Noel Perrin