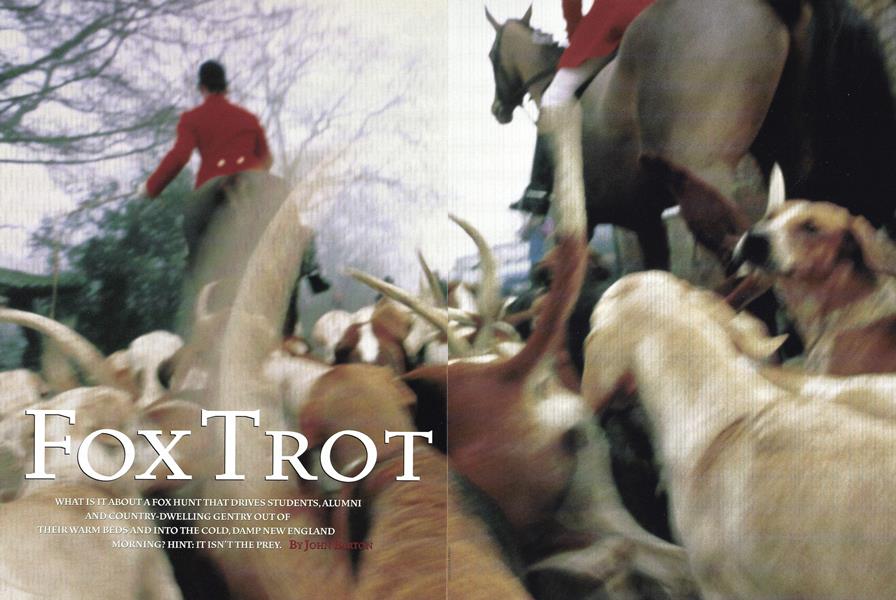

Fox Trot

What is it about a fox hunt that drives students, alumni and country-dwelling gentry out of their warm beds and into the cold, damp New England morning? Hint: It isn’t the prey.

Sept/Oct 2000 John BartonWhat is it about a fox hunt that drives students, alumni and country-dwelling gentry out of their warm beds and into the cold, damp New England morning? Hint: It isn’t the prey.

Sept/Oct 2000 John BartonWHAT IS IT ABOUT A FOX HUNT THAT DRIVES STUDENTS, ALUMNIAND COUNTRY-DWELLING GENTRY OUT OFTHEIR WARM BED| AND INTO THE COLD, DAMP NEW ENGLANDMORNING? HINT: IT ISN'T THE PREY.

YOU MIGHT THINK THE GOAL OF FOXHUNTING IS TO KILL foxes. The members of North Country Hounds—a motley collection of Dartmouth students, alumni, Hanover residents and other assorted locals—have never killed a fox. Some have never even seen a fox.

"We like to call it fox chasing, not fox hunting," says Dr. John Ketterer, a member of the Dartmouth Medical School faculty who founded the club in 1983. "Fox aerobics, you might say"

We are driving across New Hampshire in his Ford 4x4 toward the Meet, or the Hunt, or whatever it is properly called in huntspeak. It's a Sunday morning in November. It is snowing.

Ketterer is a 64-year-old gynecologist, husband and father of three. On certain mornings between August and December, he dons a scarlet jacket, horn and riding crop to transform himself into something called the Master of Foxhounds.

"I rode a bit when I was young," he says. "Then a little over 20 years ago, my daughter wanted a pony, so I got myself a horse, too. I started riding with a hunt club—it was a fun activity that you could do with other people. You can do it all your life, at any age."

The snowflakes get thicker, and faster. Riding behind us, silent in a large gray trailer, are Oliver and Cromwell, two of Ketterer s favorite horses. "Killing a fox just isn't appealing," he says. "Besides, we want him to be there next time so we can go after him again." The thrill of the chase.

We pull into Center Harbor, New Hampshire, a 60-mile drive east of Hanover, and enter a field on several thousand acres belonging to Nat and Arabella Dane. Other riders start to arrive, horse trailers in tow. Ketterer has kindly offered to sit out the hunt today; instead he'll drive me around in his Ford to watch the action. He introduces Susan Kraatz, the club's joint Master of Foxhounds, who will take his place as the leader of the pack. She and her husband, Michael, look after the hounds. They are both glass blowers.

As is tradition, Susans hair is encased in a net beneath her hunting hat. The explanation is to be found in a 1962 booklet Ketterer has given me called Riding to Hounds in America. "Your locks may be your crowning glory at other times," advises author William Wad sworth, "but nothing looks worse on a woman in the hunting field than loose flowing tresses."

It is close to freezing. I ask the president of North Country Hounds, Vernon Studer, if he doesn't get cold riding on such a day. "Your feet get cold," he replies. "But then they get numb and you don't feel them, which is better."

Brook Cosby '00, captain of the Dartmouth equestrian team, sits atop a handsome steed named L.B. It's tough trying to fit in riding practice with such pesky intrusions as classes and exams, she admits. "But riding can be a wonderful stress-reliever," she says.

Brad Rohdenburg, a pilot for American Airlines, is having his cravat tied for him and pinned in place. I ask him which is easier to drive, a plane or a horse. "Planes tend to be a bit more cooperative," he says. "They don't argue."

Brad is planning to take it easy today. The day before, he had been in a big hunt at the Myopia Hunt Club near Boston, with more than 150 riders taking part, and his horse, an excitable gelding called Checkmate, had run headlong into a fencepost. "I can remember seeing my boots against the sky," he says. "I got launched like the space shuttle."

His riding shirt is still muddy from the fall, a definite no-no, according to Riding to Hounds in America." Don't let the Master see," pleads Brad.

FOX HUNTING HAS BEEN AROUND SINCE AT LEAST THE 15th century in England, and it's been popular in the United States for more than 250 years. George Washington's diary entry of March 2,1768, reads: "Hunting again, and catchd a fox with a bob Tail and cut Ears after seven hours chase in which most of the Dogs were worsted." There are currently 171 official hunt clubs across America.

To say the fox is elusive in these parts would be a massive understatement. The fox population isn't nearly as dense as in the U.K. (where the sport is extremely controversial and faces a possible government ban). There's more land here, predators such as coyotes abound, and rabies has kept numbers low.

"The fox has all sorts of tricks," adds Ketterer. "He runs across a stream or through a fresh manure field or along the top of a fence. The gray fox can climb a tree to get away, and the red fox dives into a hole in the ground."

To those of us who despair at the barbaric treatment humans habitually inflict upon animals, the news that fox hunting here does not depend on the participation of the fox is welcome indeed. For the rest, it may seem quite absurd. A foxless fox hunt, you say? You snort with indignation. What's the point? To ask what the point is, my friend, is to miss the point entirely. There are many avenues of human endeavor that are pursued with great passion, yet to outsiders seem to have no point (each, of course, comes with its own strange clothes, eccentric rituals and foolish incantations). Golf, for instance, or rooting for the Red Sox. On the same day as the hunt,30,000 souls ran 26.2 miles through the streets of New York of their own volition, despite the fact that there are many more efficient methods of getting from Staten Island to Central Park. People do not run marathons to get from A to B anymore, but to run. Similarly, the purpose of the hunt nowadays is not to kill a fox, but to hunt. The means becomes the end.

ABOUT 25 PEOPLE FROMTHE 50-STRONG NORTH COUNTRY Hounds membership have braved the cold winds and flurries for todays proceedings. They are joined by a couple of "cappers," guests of members who pay a kind of greens fee of $40 to ride along. But the real talent, the true stars of this show, are not among them. That role is reserved for—who else—the hounds! They are pure Hollywood; canine athletes bristling with a regal intelligence and tiptop physical conditioning. If they were humans, theyd wear expensive suits and vacation in Maui. A month earlier there had been the annual "Blessing of the Hounds" ceremony, with a robed priest offering a benediction to the pampered pooches.

The ancestry of American foxhounds goes back to English hounds imported to this country in 1650. Aside from their physical appearance—long, elegant bones, strongly muscled thighs and furiously wagging curved tails—the most impressive thing about them is the fact that they sound like a chorus line. Says one doggie guidebook: "The songlike voice of the American foxhound has been recorded and incorporated into popular music."

The riders, now all in their finery, assemble in a group and Ketterer performs an official welcome speech. The riders' regalia, in the case of the North Country Hounds, consists of knee-length boots, cream-colored breeches, white shirt and cravat, a yellow tweed vest and a coat—scarlet for the leaders, black for everyone else. Those who have earned their club "colors"—sky blue with green trim—wear them on their coat collar.

The party heads off across a field, and we return to the Ford to follow the proceedings by road. The shortcomings of a 4x4 as compared to a horse immediately become apparent. We can't see anything. Generally speaking, fox hunting is not a great spectator sport.

We pull over and shoulder our way through some trees. Suddenly we are in an 18th-century English oil painting: Before us lies a classic, ancient scene, with the horses and hounds moving majestically down the field, to the sublime backdrop of Squam Lake and New Hampshire's gentle, shrouded hills.

Albert Ellis '80 trots by and stops for a chat. He is a capper from the Myopia club. For some reason we start talking about golf in Scotland. We agree that todays biting wind would be considered only average at Muirfield. Then he canters off.

The riders disappear, and we drive back along the road. For the rest of the morning we catch occasional glimpes of the pack, or hear distant cries of Susans horn, the odd whinny from a horse or a bark from a hound. We follow the hunt s progress on Ketterers walkie-talkie. "The hounds are running in Pipers Field!" crackles Susans excited voice at one point. But then a few minutes later: "Ah, they seem to have lost it." The hounds, it seems, were "running trash"—chasing a fake scent.

We watch the snowflakes falling through the trees, occasionally illuminated by an unexpected shaft of sunlight. Good hunting conditions are when the ground is warm, the air is cold and there's no wind. Today, everything is cold, the wind has destroyed any scent trails, and it's playing havoc with man-dog communication. We would hear no cries of "Tally ho!" today.

After a couple of hours, it's almost time to wrap things up. Then, suddenly, we see a small avalanche of hounds cross the little lane where we're parked and disappear into a densely forested area on the other side. The hounds have entered uncharted territory, and no amount of blows on the horn or peculiar shrieks from Susan bring them back. "Live free or die," the hounds seem to be suggesting.

As so often happens, the fox hunt has turned into a hound hunt, something that is made a little easier these days by the radio collars that all the hounds wear. "In the old days, we'd be out retrieving the hounds for the rest of the afternoon, sometimes into the evening and even the next day," says Ketterer.

Over the next hour, the hounds are rounded up one by one and put back into the hound truck. Battle is caught, soon followed by his siblings Bagpipe and Brilliant (hounds from one litter are all given names starting with the same letter). The Master knows all the hounds intimately. When we hear a strangulated cry from deep in the forest, Susan instantly knows it is Sybil, and sure enough, moments later Sybil appears sporting a muddy back and a big grin. She is reunited with her colleagues to the accompaniment of much excited baying. The last two hounds still on the loose are Bugle and Blissful. Eventually, like Steve McQueen in The Great Escape, they are cornered, caught and returned to the truck.

WE ALL REPAIRTO THE DANES' FARMHOUSE FOR LUNCH, which naturally is not called lunch in hunt language but, instead, breakfast. There is a sumptuous spread laid out for all the hungry riders. A warm hearth, good food, rosy cheeks and lots of conversation.

Now it all makes sense.

"Beautiful country," everyone tells Arabella, in the tone of voice normally reserved for compliments on one's choice of wallpaper.

Sally Boillotat, who runs the Dartmouth Riding Center out of the 20-year-old Morton Farm, eight miles from campus, is talking horses. She lives and breathes horses. She even majored in horses (one can, apparently, study for a B.A. in equine studies). "I've just always been into animals," she says. "When I was a teenager, I really loved horses. My parents said, 'You'll grow out of it.' But I never did."

Each season Sally takes between 15 and 20 riders along to hunt with the North Country Hounds as guests (each August there is a "houndless hunt"—an introductory clinic to foxhunting for beginners). She also coaches the intercollegiate team and gives lessons to both Dartmouth students and locals. Riding is certainly a popular activity in these parts—around 150 people show up for lessons each week. The day before I had counted 11 different horse magazines in the Dartmouth Bookstore.

Meanwhile, the master of the house is holding court by the fireplace, espousing his views on gun control, farm animals and his alma mater, Harvard. ("Most of these people went to Dartmouth," he says, surveying the room, "but otherwise they're fine people.") "People who are truly interested in this sport take much better care of the land and the animals than anyone else," he says.

I fall into conversation with John Bacon '71, the principal of a local middle school. He tells me about his first hunt, more than 20 years ago.

"Fifteen minutes into it, we saw a fox," he says. "And we all set off chasing it. The fox led us across fields, we jumped over fences. It was thrilling. The fox got away, of course. You know, I've been hunting regularly ever since, and I've never seen another fox."

Only one of the riders, the club secretary, had seen a fox to-day. There had been few trails in the freezing, windy conditions. And the last third of the hunt had been spent rounding up the free-spirited hounds. So I ask the Master, Susan, how she would characterize the days proceedings.

"I'm thrilled," she says over a steaming bowl of soup. "It's only the fourth time we've hunted this country so we don't know it all that well yet, but I think it went really well."

How would she feel if the hounds ever did actually catch and kill a fox? "That's what's nice about the sport here," she says. "The fox is never threatened. It's entirely his own game—we know it, and I even think the fox knows it."

For Susan and the others, it's not too much of a stretch to imagine that the fox actually enjoys the hunt as much as they do. Writes Wadsworth in Riding to Hounds in America: "I am convinced that he [the fox] also is a sportsman and has a sense of humor, as I can see no other reason for a fox to stay above ground and permit himself to be hunted in a country so full of holes."

Breakfast is finished. Before we head back to Hanover, Arabella introduces us to her goat and her pet pig, a fiery redhead. The pig and the goat don't always get along, but today they sniff each other approvingly. There is probably within us all some ancient, timeworn Urge to hunt and gather, from long ago, when these activities didn't involve shopping carts and coupons. But standing here today, surrounded by pigs, goats, horses, hounds and humans, suddenly you can't help but feel an inexplicable kinship with one's fellow mammals.

As Susan had said earlier: "Who on earth would want to kill a fox?"

Oay.Afternoon The horses are majestic, but the stars of this show are the hounds, even if it may take the better part of the day to round them up afterward.

Tally Ho Clockwise from right: The Master of the Hunt with medals from the "Blessing of the Hounds;'' eager hounds await the hunt; saddling up; a hound's-eye view of breakfast.

"WE LIKE TO CALL IT FOX CHASING, NOT FOX HUNTING. FOX AEROBICS, YOU MIGHT SAY."

"THE FOX IS NEVER THREATENED. WE KNOW IT, AND I EVEN THINK THE FOX KNOWS IT."

JOHN BARTON is a senior editor for Golf Digest magazine. He livesin Connecticut.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

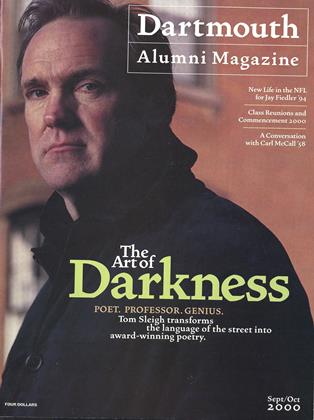

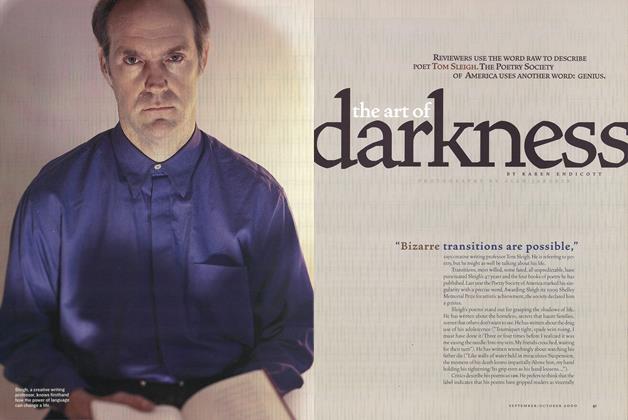

Cover StoryThe Art of Darkness

September | October 2000 By KAREN ENDICOTT -

Feature

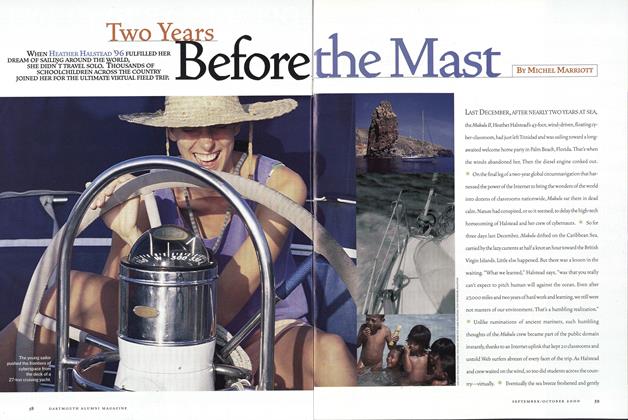

FeatureTwo Years Before The Mast

September | October 2000 By Michel Marriott -

Feature

FeatureCommencement and Reunions: A Sketchbook

September | October 2000 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYWhat is Perfect?

September | October 2000 By Mary Cleary Kiely ’79 -

Sports

SportsMaking all the Right Moves

September | October 2000 By Brad Parks '96 -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMCode of Life, Codes of Conduct

September | October 2000 By Karen Endicott

Features

-

Feature

FeatureFaces in the Gallery

MARCH 1978 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryRobert Harris Upham 1832

NOVEMBER 1990 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO FIND HEAVEN ON TWO WHEELS

Sept/Oct 2001 By ANNELIE CHAPMAN '86 -

Feature

FeatureThe Lovinses and the Soft-Energy Path

JUNE 1982 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Feature

FeatureAfter Iran: Can We Have a Foreign Policy?

NOVEMBER • 1987 By Stephen Bosworth '61 -

COVER STORY

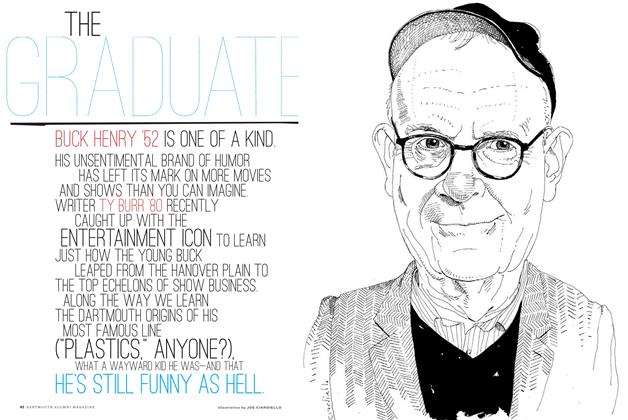

COVER STORYThe Graduate

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2013 By Ty Burr ’80