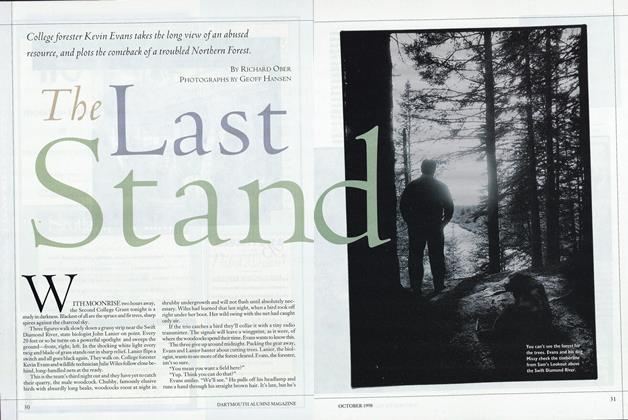

The Art of Darkness

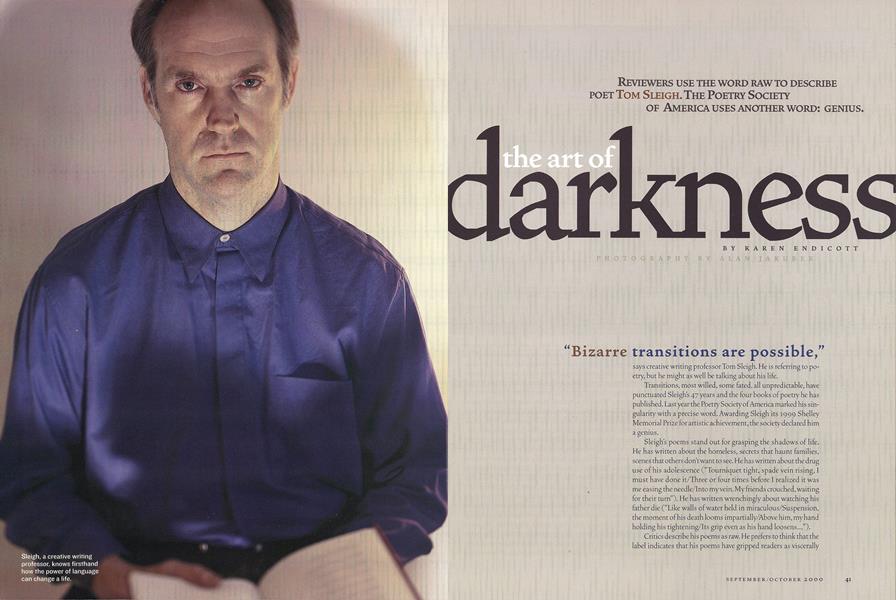

Reviewers use the word raw to describe poet Tom Sleigh. The Poetry Society of America uses another word: Genius.

Sept/Oct 2000 KAREN ENDICOTTReviewers use the word raw to describe poet Tom Sleigh. The Poetry Society of America uses another word: Genius.

Sept/Oct 2000 KAREN ENDICOTTREVIEWERS USE THE WORD RAW TO DESCRIBE POET TOM SLEIGH. THE POETRY SOCIETY OF AMERICA USES ANOTHER WORD: GENIUS.

"Bizarre transitions are possible," says creative writing professor Tom Sleigh. He is referring to poetry but he might as well be talking about his life.

Transitions, most willed, some fated, all unpredictable, have punctuated Sleigh's 47 years and the four books of poetry he has" published. Last year the Poetry Society of America marked his singularity with a precise word. Awarding Sleigh its 1999 Shelley Memorial Prize for artistic achievement,the society declared him a genius.

Sleighs poems stand out for grasping the shadows of life. He written about the homeless, secrets that haunt families, scenes that others don't want to see. He has written about the drug use of his adplescence ("Tourniquet tight, spade rising, I must have done it/Three or four times before I realized it was me easing the needle/Into my vein. My friends crouched, waiting for their turn"). He has written wtenchingly about watching his father die ("Like walls of water held in miraculous/Suspension, the moment of his death looms impartially/Above him, my hand holding his tightening/Its grip even: as his hand loosens...").

Critics describe his poems.as raw. He prefers to think that the label indicates that his poems have gripped readers as viscerally as the subject matter gripped him. "As a poet you're helpless," he says. "Your material chooses you. You don't sit down and say, 'l'm going to write a poem about leaves.' If you do, the work goes dead. There has to be an emotive background to a poem."

Outwardly, the poet—trim and casually polished—carries no sign of the emotive turmoil behind his poetry. But this comfort did not come easily.

Sleigh was not born into heady, high culture. He grew up in rural Texas and Utah, where vast plains offered wide-open views but few cultural vistas. He fed his imagination with books, an obsession kindled by his mother, a high school teacher. In adolescence Sleigh moved to San Diego with his family. He found a wider world but not contentment. He yearned for adventure. At 14 he turned to drugs. At 16 he stashed a dictionary and a volume of Shakespeare in a pillowcase and ran away into the city. "I didn't understand at the time why I was so desperate to get out," he says.

Easy prey for a newspaper ad promising a trip to the Caribbean to salvage-dive for treasure, Sleigh joined a group of misfits and drifters who repaired and sold boats and cars to earn passage to the islands. "Only a teenager would believe that was going to happen," he says. After months of living in buses, scrounging for food and working 12- to 15-hour days with no Caribbean trip in sight, he gave up.

Homeless, he landed on the street. He slept in doorways. He spare-changed and got high. And he grew fascinated with the people he encountered on the street. "Some were hilarious, some were tragic. Everyone had crazy particularities—like people every where," he says. At the same time, he loathed the ruthlessness of the drug scene. "I hated the paranoia of an atmosphere where 'creatures' would turn people in without warning. Relationships were only as good as what you could supply or get," he says. Within a few months, even his drug thrills wore thin. "I could control LSD highs like an elevator," he says. Sleigh decided to quit street life. But he never fully left the street—and its lingo—behind. "The specialized language of the drug community was my first exposure to heightened language," he says. "I saw the power of language to transform your own world."

Sleigh transformed his situation by returning home and renegotiating his place in his family. He graduated from high school and entered the California Institute of the Arts. After one semester, another diversion lured him away. Hitchhiking through California, he heard about an anthropologist named Gertrude Blom, who was conducting field work in Chiapas, Mexico. He arranged to join the project, headed to Mexico and assisted with clerical and library work. In his free time he wrote prose sketches of the people and scenes around him.

Yet something was missing. For months he spoke nothing but Spanish. "I got really lonely for English," he says. He combed shops for English books and finally found one. Opening it, he read: "I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked, dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix..."

"This was English like I'd never heard it before," Sleigh says.

He had discovered Allen Ginsbergs poem "Howl."

When his stint in Chiapas was up, Sleigh returned to San Diego. Still thinking in prose, he wanted to write about how his mother freed herself from a hardscrabble childhood on the Kansas prairie. "I thought that understanding her life would help me understand mine," he says. "What I didn't understand was that that's not really important in a work of art."

He also didn't realize how high and inappropriately he had set his literary bar: his model for storytelling was Virginia Woolf's complex novel To the Lighthouse. He adopted Woolf's mode of lyrical delicacy and florid scene painting. But he found that the style jarred with his mother's experiences. "The means was hopeless to the task," he says. "The medium was not mine."

Sleigh enrolled in Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington, and there he started to write poetry. He immersed himself in T.S. Eliot, Anne Sexton, Sylvia Plath. He found poetry liberating. "Freed from narrative," he says, "you're free to make strange associations."

Hed found his medium. Sleigh sped ahead, completing a masters degree in creative writing at Johns Hopkins. Heworked odd jobs to support his writing, then won a fellowship to the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, Massachusetts. He spent another few years living hand-to-mouth in Boston while writing poetry. His first book of poems, After One, was published by Houghton Mifflin in 1983, when he was 30. The volume commanded immediate attention. One of the first reviews, appearing in The NewYork Times Book Review, was written by poet Robert Pack '51, a professor at Middlebury: "In language that is rhythmic, spare and lucid, he rewards his readers with poems genuinely designed with what [Robert] Frost called 'a good look and a good listen.' " Two years later, in 1985, Dartmouth hired Sleigh to teach creative writing, and he began commuting to Hanover from his Cambridge apartment.

Teaching was a part of life Sleigh could control. It stood in contrast to a side of life that had stolen upon him seven years earlier. In 1978 Sleigh had developed a chronic, life-threatening blood condition known as paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Ever since, he has had to struggle with the physical and emotional effects of the condition. He devoted most of 1987 and hundreds of draft pages to distill his thoughts about the illness. The result was "Ending," a 12-page poem that begins:

When I first learned I went home to lie down. The fear in me took me by the throat. What I had wished for-that my life Would be a hook, and the hook a paradigm Of suffering I could not escape, suffering Whose knowledge would be impossible to bear Even as I braced and kept bracing To bear ithad been granted. Until then I had loathed My safety-now I saw disaster

"Ending" marked a new beginning for Sleigh, according to poet Frank Bidart. "He raised the bar with that poem." Bidart, a Wellesley professor who knows Sleigh and his poems well enough that they show each other new work, praises Sleighs poetry as a "rare combination of formal sophistication and remarkable emotional nakedness. He is not just writing out of his own personal past. He writes out of a tradition of world poetry."

As a professor, Sleigh knows that most of his students will not become poets. "A few are obsessed in all the right ways," he says. "Others want to learn to express themselves. I look for the part of the writing that has a charge, then encourage them to raise the rest of the poem to that level." He directs all to poets they should read. "I try to give students a sense of how high the bar is," he says.

"Tom is able to convey the seriousness of working in the tradition without intimidating students who are doing something new," says former student Peter Campion '98. Currently a master's student in poetry at Boston University, Campion admires Sleighs writing as much as his teaching. "Tom's poems are part of a tradition of intensely felt art which challenges social conventions," he says. "Tom is dark, but so is Caravaggio."

Sleighs darkness is increasingly attracting the literary limelight. The Shelley Memorial Award has brought him national prominence. His most recent volume of poems, The Dreamhouse (The University of Chicago Press, 1999), was selected by the Academy of American Poets bookclub and was nominated for zLosAngelesTimes Book Prize. "It's good to have a certain amount of reputation, but that's mercurial," Sleigh says. What matters, he says, is staying fresh.

Sleigh has been challenging himself with a new literary venture: play writing. He has written three plays and is open to writing more. "If something announces itself as a play, I'll write it as a play," he says. Play writing may seem as bizarre a transition from poetry as the street was from the rest of his life. But Sleigh, who has also written about half of his next collection of poems, takes a different view. "What others see as separate activities, I don't," he says. "I would hate it if I never wrote another poem."

Excerpt from "Ending" from Waking © 1990 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved.

Sleigh, a creative writing professor, knows firsthand how the power of language can change a life.

"It's good to have a certain amount of reputation, but that's mercurial," Sleigh says. "What matters is staying fresh."

"TOM'S POEMS CHALLENGE SOCIAL CONVENTIONS," SAYS FORMER STUDENT PETER CAMPION '98. "TOM IS DARK, BUT SO IS CARAVAGGIO."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

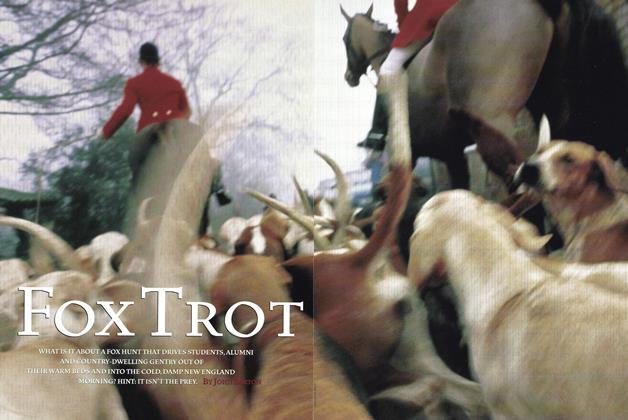

FeatureFox Trot

September | October 2000 By John Barton -

Feature

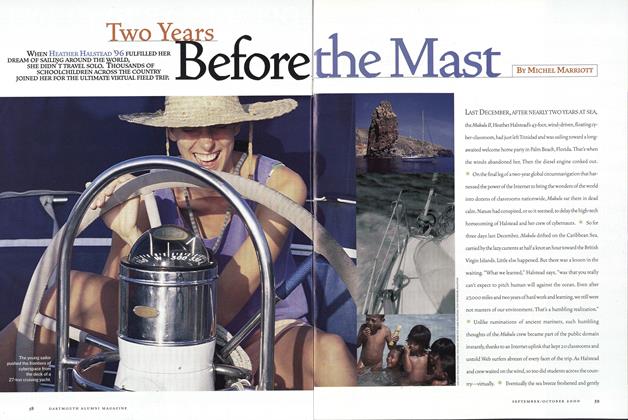

FeatureTwo Years Before The Mast

September | October 2000 By Michel Marriott -

Feature

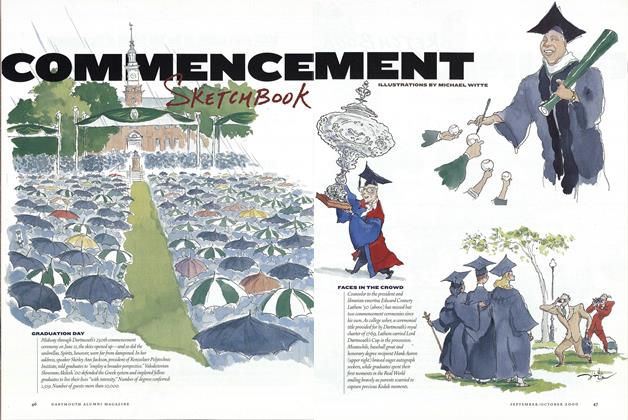

FeatureCommencement and Reunions: A Sketchbook

September | October 2000 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYWhat is Perfect?

September | October 2000 By Mary Cleary Kiely ’79 -

Sports

SportsMaking all the Right Moves

September | October 2000 By Brad Parks '96 -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMCode of Life, Codes of Conduct

September | October 2000 By Karen Endicott

KAREN ENDICOTT

-

Article

ArticleA Hero in American Education

NOVEMBER 1989 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleOut But Not Down

May 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleA Cautionary Tale

April 1995 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleVisions of the Ancestors

MAY 1996 By Karen Endicott -

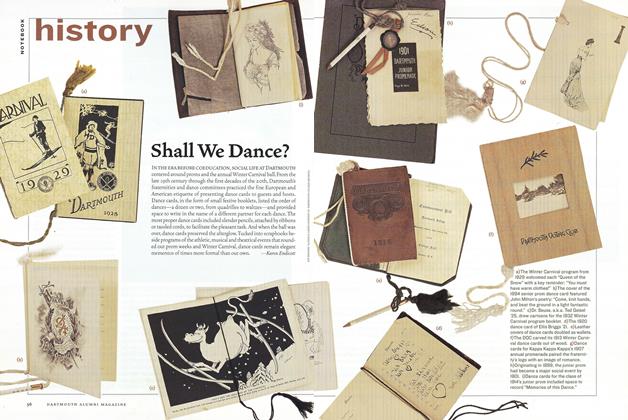

HISTORY

HISTORYShall We Dance?

Sept/Oct 2000 By Karen Endicott -

Classroom

ClassroomThe Art and Science of Group Dynamics

Nov/Dec 2002 By Karen Endicott