QUOTE/UNQUOTE "When someone like Dana Meadows dies, it is not just we who pause and reflect. It is the white pines that bow their tops a little bit, and the deer stop short for no clear reason." —WRITER BILL MCKIBBEN SPEAKING IK ALUMNI HALL ON THE PROFESSOR'S DEATH IN FEBRUARY

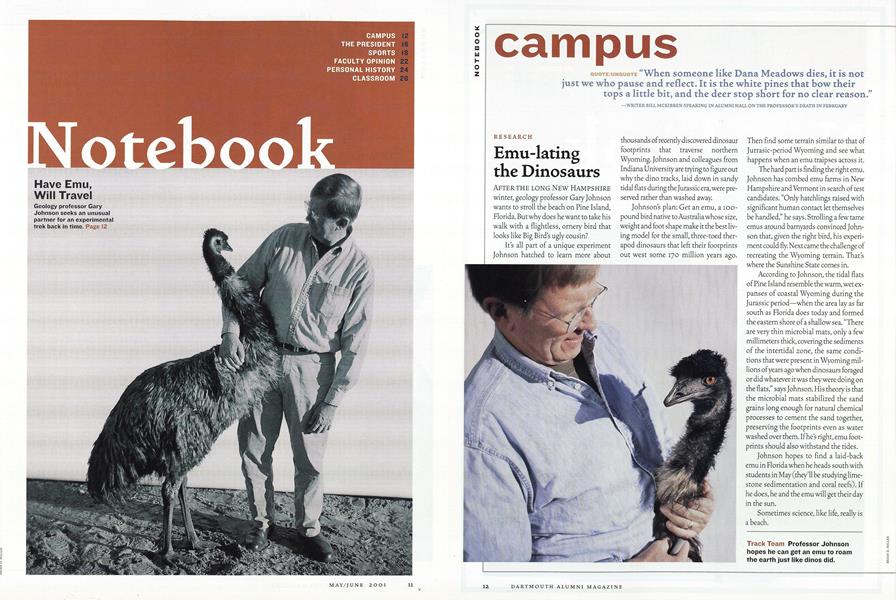

AFTER THE LONG NEW HAMPSHIRE winter, geology professor Gary Johnson wants to stroll the beach on Pine Island, Florida. But why does he want to take his walk with a flightless, ornery bird that looks like Big Bird s ugly cousin?

It's all part of a unique experiment Johnson hatched to learn more about thousands of recently discovered dinosaur footprints that traverse northern Wyoming. Johnson and colleagues from Indiana University are trying to figure out why the dino tracks, laid down in sandy tidal flats during the Jurassic era, were preserved rather than washed away.

Johnsons plan: Get an emu, a 100-pound bird native to Australia whose size, weight and foot shape make it the best living model for the small, three-toed therapod dinosaurs that left their footprints out west some 170 million years ago. Then find some terrain similar to that of Jurrasic-period Wyoming and see what happens when an emu traipses across it.

The hard part is finding the right emu. Johnson has combed emu farms in New Hampshire and Vermont in search of test candidates. "Only hatchlings raised with significant human contact let themselves be handled," he says. Strolling a few tame emus around barnyards convinced Johnson that, given the right bird, his experiment could fly. Next came the challenge of recreating the Wyoming terrain. That's where the Sunshine State comes in.

According to Johnson, the tidal flats of Pine Island resemble the warm, wet expanses of coastal Wyoming during the Jurassic period—when the area lay as far south as Florida does today and formed the eastern shore of a shallow sea. "There are very thin microbial mats, only a few millimeters thick, covering the sediments of the intertidal zone, the same conditions that were present in Wyoming millions of years ago when dinosaurs foraged or did whatever it was they were doing on the flats," says Johnson. His theory is that the microbial mats stabilized the sand grains long enough for natural chemical processes to cement the sand together, preserving the footprints even as water washed over them. If he's right, emu footprints should also withstand the tides.

Johnson hopes to find a laid-back emu in Florida when he heads south with students in May (they'll be studying limestone sedimentation and coral reefs). If he does, he and the emu will get their day in the sun.

Sometimes science, like life, really is a beach.

Track Team Professor Johnsonhopes he can get an emu to roamthe earth just like dinos did.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Life in the Wild

May | June 2001 By NELSON BRYANT ’46 -

Feature

FeatureShooting the Grant

May | June 2001 By BEN YEOMANS -

Feature

FeatureVoices in the Wilderness

May | June 2001 By Jennifer Kay '01 -

Feature

FeatureTHE GREAT NORTH WOODS

May | June 2001 By Michelle Chin '03 -

Cover Story

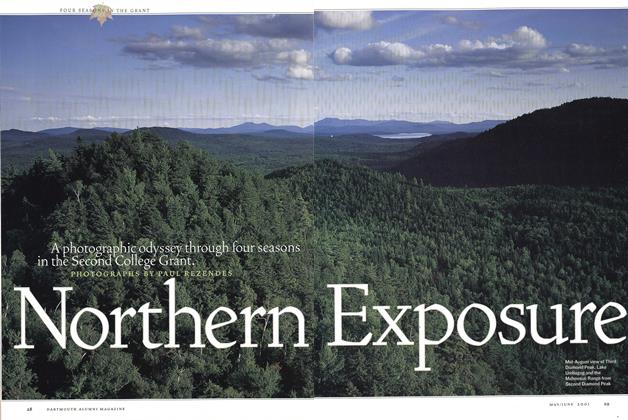

Cover StoryNorthern Exposure

May | June 2001 -

Sports

SportsThe Sporting Life

May | June 2001 By Lily Maclean ’01

Article

-

Article

ArticleTHE ORIGINS OF DELTA ALPHA—A SYMPOSIUM

March, 1923 -

Article

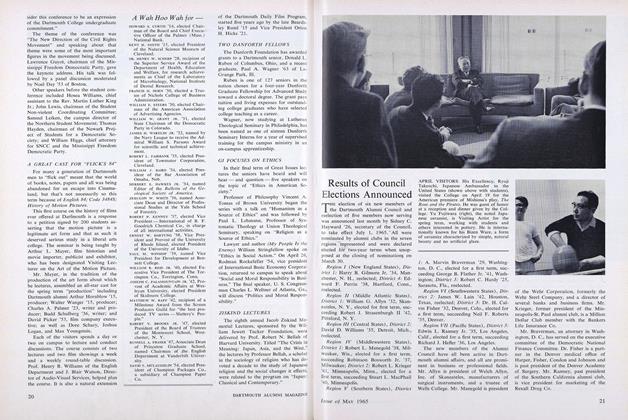

ArticleResults of Council Elections Announced

MAY 1965 -

Article

ArticleWrestling

MARCH 1959 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

February 1953 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHow to Fix the Fed

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2014 By Peter Fisher -

Article

ArticleAlumni News

Jul/Aug 2004 By Susan Hamilton Munoz '92