Loaded Canon

A call to depoliticize the curriculum and teach the greatest works of all cultures.

Mar/Apr 2003 Dinesh D’Souza ’83A call to depoliticize the curriculum and teach the greatest works of all cultures.

Mar/Apr 2003 Dinesh D’Souza ’83A call to depoliticize the curriculum and teach the greatest works of all cultures.

IN 1980, AS A FRESHMAN AT Dartmouth, I attended several meetings sponsored by the International Students Association. I enjoyed these meetings because it was an opportu- nity to eat good ethnic food. It was in these venues that I first encountered that most intriguing creature, the mul- ticulturalist. The multiculturalist that I remember was a white guy who wore a ponytail and a Nehru jacket. He was visibly excited to meet a fellow from India.

"So you're from India," he said. "What a great country."

"Have you ever been there?" I asked.

"No," he confessed. "But I've always wanted to go."

"Why?" I asked, genuinely curious.

"I don't know," he said. "It's justso liberating!"

Having had a happy childhood in India, there are many nice things I have to say about my native country, but if I had to choose one word to describe life there, I probably wouldn't choose "liberating." I decided to prod my enthusiastic acquaintance a little.

"What is it that you find so liberating about India?" I asked. "Could it be—the caste system? Dowry? Arranged marriage?"

My purpose was to challenge him, to generate a discussion. But at this point he lost interest. My question ran into a wall of indifference.

"Got to get another drink," he said, racing toward the bar.

I tried the same experiment several times, always with a similar result. And as I reflected on the matter, a thought occurred to me. Maybe these students weren't really so interested in India at all. Maybe they were projecting their domestic discontents with their parents, their preachers or their country onto the faraway land of India. Maybe they were imagining India to be something that she was not: a land of social liberation, where the conventional restraints were completely lifted. While I sympathized to some degree with these aspirations, I also resented this exploitation of India for political ends. "You are entitled to your illusions," I wanted to tell the ponytailed guy, "but India simply is not like that."

I mention this anecdote because it was an early indication of a phenomenon I was to investigate later, the phenomenon of bogus multiculturalism.

Multiculturalism is a movement to transform the curriculum and the way that things are taught in our schools and universities. Some people think that its triumph is inevitable. Thus sociologist Nathan Glazer a few years ago wrote a book called We Are AllMulticulturalists Now. Glazer is not entirely enthusiastic about multiculturalism. He is convinced, however, that because America has become so racially diverse, multiculturalism is unavoidable. Glazer s mistake is to confuse the fact of the multiracial society with the ideology of multiculturalism. The two are quite distinct, and the latter is not necessarily the best way to respond to the former.

To understand the multicultural debate it may be helpful to begin with Allan Blooms 1987 book The Closingof the American Mind. Bloom argued that American students are shockingly ignorant of the basic ingredients of their own Western civilization. Even graduates of the best colleges and universities have a very poor comprehension of the thinkers and ideas that have shaped their culture. Thus Ivy League graduates know that Homer composed The Odyssey and that Aquinas lived during the Middle Ages and that Max Weber's last name is pronounced with a "V." But most of them aren't sure whether the Renaissance came before the Reformation, they couldn't tell you what was going on in Britain during the French Revolution, and they look bewildered if you ask them why the American founders considered representative democracy an improvement over the kind of direct democracy that the Athenians had. In short, Bloom concluded that even "educated" Americans were not really educated at all.

Blooms ideas came under fierce assault, and leading the charge were proponents of multiculturalism. Multiculturalism is, as the name suggests, a doctrine of culture. Advocates of multiculturalism, such as literary critic Cornel West and historian Ronald Takaki, say that for too long the curriculum in our schools has focused exclusively on Western culture. In short, it is "Eurocentric." The problem, multiculturalists say, is not that students are insufficiently exposed to the Western perspective; it is that the Western perspective is all that they are exposed to.

What is needed, multiculturalists insist, is an expansion of perspectives to also teach minority and non-Western cultures. This is especially vital, in their view, because we are living in an interconnected global culture and there are increasing numbers of black, Hispanic and Asian faces in the classroom. Multiculturalism presents itself as an attempt to give all students a more complete and balanced education, so that they can get the full picture.

Stated this way, multiculturalism seems unobjectionable and uncontroversial. But the reason it is controversial is that there is a powerful political thrust behind the way multiculturalism works in practice. To discover this ideological thrust, we must look at multicultural programs as they are actually implemented. Several years ago I did my first study of a multicultural curriculum, at Stanford University. I pored over the reading list, looking for the great works of non-Western culture: the Koran, the Ramayana, the Analects of Confucius, the Tale of Genji, the Gitanjali and so on. But they were nowhere to be found. As I sat in on classes, I found myself presented with a picture of nonWestern cultures that was unrecognizable to me as a person who had grown up in one of those cultures. Our typical reading consisted of works such as I, RigobertaMenchu, the 1983 autobiography of a young Marxist feminist activist in Guatemala.

Now I don't mean to understate the importance of Guatemalan Marxist feminism as a global theme. But were students encountering the best literary output of Latin American culture? Was I,Rigoberta Menchu even representative of the culture of the people of Guatemala? The answer to these questions was clearly no. So why were Stanford students being exposed to this stuff?

It is impossible to understand multiculturalism in America without realizing that it arises from the powerful conviction that Western civilization in general, and America in particular, are defined by bigotry and oppression. The targets of this maltreatment are, of course, minorities, women and homosexuals. And so the multiculturalists look abroad, hoping to find in other countries a better alternative to the bigoted and discriminatory ways of the West.

And what do they find? If they look honestly, they soon discover that other cultures are even more bigoted than those of the West. Ethnocentrism and discrimination are universal; it is the doctrine of equality of rights under the law that is uniquely Western. Women are treated quite badly in most non-Western cultures: think of such customs as the veil, female foot-binding, clitoral mutilation, the tossing of females onto the burning pyres of their dead husbands. As a boy I learned the following saying: "I asked the Burmese why, after centuries of following their men, the women now walk in front. He explained that there were many unexploded land mines since the war." This is intended half-jokingly, but only halfjokingly. It conveys an attitude toward women that is fairly widespread in Asia, Africa and South America. As for homosexuality, it is variously classified as an illness or a crime in most non-Western cultures. The Chinese, for example, have a longstanding policy of administering shock treatment to homosexuals, a practice that one government official credits with a "high cure rate."

Of course non-Western cultures have produced many classics or great books, and these are eminently worthy of study. But, not surprisingly, those classics frequently convey the same unenlightened views of minorities and women that the multiculturalists deplore in the West. The Koran, for instance, is the central spiritual document of one of the worlds great religions, but one can not read it without finding in it a clear doctrine of male superiority. The Tale ofGenji, the Japanese classic of the nth century, is a story of hierarchy, of ritual, of life at the court: It is far removed from the Western ideal of egalitarianism. The Indian classics—the Vedas, the BhagavadGita and so on—are celebrations of transcendental virtues: They are a rejection of materialism, of atheism, perhaps even of separation of church and state.

What I am saying is that non-Western cultures, and the classics that they have produced, are for the most part politically incorrect.

This poses a grave problem for American multiculturalists. One option for them is to confront non-Western cultures and to denounce them as being even more backward and retrograde than the West. This option is politically unacceptable. The reason is that non-Western cultures are viewed as historically abused and victimized. In the eyes of the multiculturalists, they deserve not criticism but affirmation. And so the multiculturalists prefer the second option: Ignore the representative traditions of non-Western cultures, pass over their great works and focus instead on marginal and isolated works that are carefully selected to cater to Western leftist prejudices about the non-Western world.

There is a revealing section of I, RigobertaMenchu where young Rigoberta proclaims herself a quadruple victim of oppression. As a person of color, she is oppressed by racism. As a woman, she is oppressed by sexism. As a Latin American, she's oppressed by the North Americans. And, finally, as someone of Indian extraction, she is oppressed by people of Spanish descent within Latin America. Here, then, is the secret of Rigobertas curricular appeal. She is not representative of the culture or great works of Latin America, but she is representative of the politics of Stanford professors. Rigoberta is, for them, a kind of model to hold up to the students, especially female and minority students. They too can think of themselves as oppressed, like her.

This is what I call bogus multiculturalism. It is bogus because it views nonWestern cultures through the ideological lens of Western leftist politics. Non-Western cultures are routinely mutilated and distorted to serve Western ideological ends. No serious understanding between cultures is possible with multiculturalism of this sort.

The alternative, in my view, is not to go back to the traditional curriculum focused on the Western classics. Rather, it is to have an authentic multiculturalism that teaches the greatest works that have been produced by all cultures. Matthew Arnold, the 19th-century English social critic, offered a resonant phrase: "the best that has been thought and said." That sums up the essence of a sound liberal arts curriculum. Probably Arnold had in mind the best of Western thought and culture. There is no reason in principle, however, that Arnolds criterion cannot be applied to non-Western cultures as well.

Personally I would like to see liberal arts colleges devote the better part of the freshman year to grounding students in the classics of Western and non-Western civilization. Yes, I am talking about requirements. To heck with electives: 17-year-olds don't know enough to figure out what they need to learn. Once they have been thoroughly grounded in the classics, there are three more years for students to choose their majors and experiment with courses in Bob Dylan and Maya Angelou. My hope, of course, is that after a year of Socrates and Confucius and Tolstoy and Tagore, most students will have lost interest in Bob Dylan and Maya Angelou.

DINESH D'SOUZA is the author of Letters to a Young Conservative (Basic Books),from which this piece has been adapted. He isthe Rishwain Research Scholar at the HooverInstitution at Stanford University.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWomen on the Verge

March | April 2003 By Jennifer Kay ’01 -

Feature

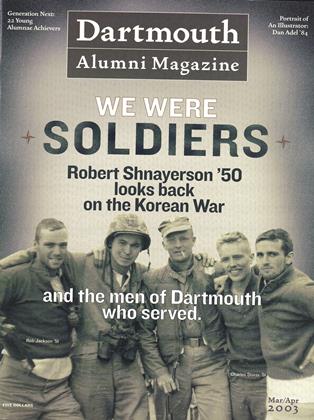

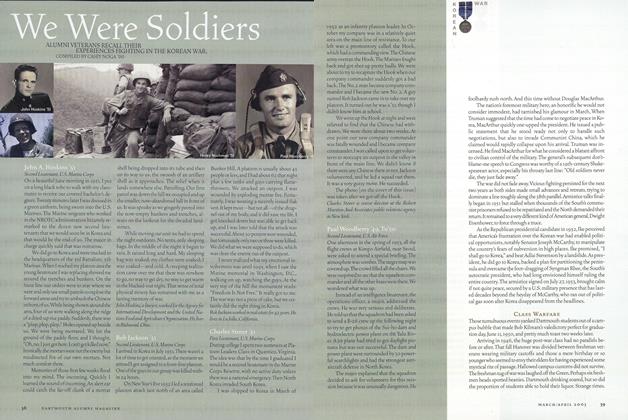

FeatureWe Were Soldiers

March | April 2003 By CASEY NOGA '00 -

Cover Story

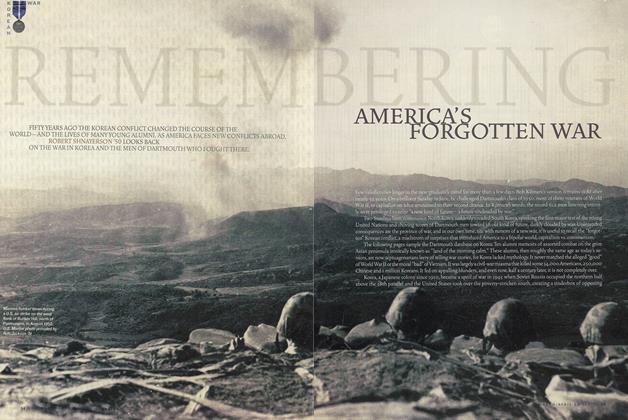

Cover StoryRemembering America’s Forgotten War

March | April 2003 By ROBERT SHNAYERSON ’50 -

Feature

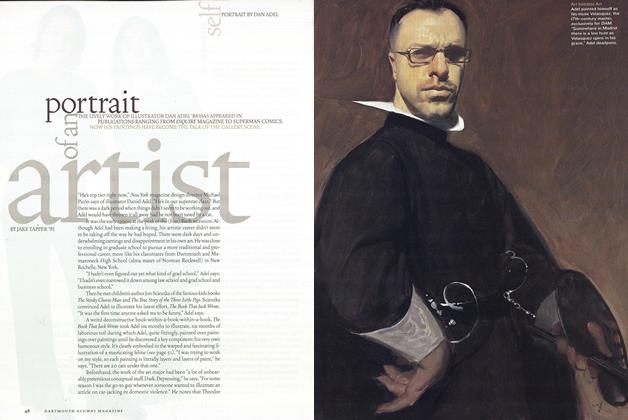

FeaturePortrait of an Artist

March | April 2003 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

March | April 2003 By MIKE MAHONEY '92 -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionThe Cost of Winning

March | April 2003 By Professor Ray Hall

Dinesh D’Souza ’83

Alumni Opinion

-

ALUMNI OPINION

ALUMNI OPINIONTime for a Bigger Tent

July/Aug 2009 By Ed Gray ’67, Tu ’71 -

Alumni Opinion

Alumni OpinionIn Praise of Class Notes

May/June 2004 By James Zug ’91 -

Alumni Opinion

Alumni OpinionDeclaration of Independence

July/August 2012 By John Fanestil ’83 -

ALUMNI OPINION

ALUMNI OPINIONFailing the Test

Nov/Dec 2006 By John Merrow ’63 -

ALUMNI OPINION

ALUMNI OPINIONA Classic Tale

Jan/Feb 2005 By John S. Martin ’86 -

Alumni Opinion

Alumni OpinionThe Ex-Wives Club

Nov/Dec 2001 By Regina Barreca ’79