Remembering America’s Forgotten War

As America faces new conflicts abroad, Robert Shnayerson ’50 looks back on the war in Korea and the men of Dartmouth who fought there.

Mar/Apr 2003 ROBERT SHNAYERSON ’50As America faces new conflicts abroad, Robert Shnayerson ’50 looks back on the war in Korea and the men of Dartmouth who fought there.

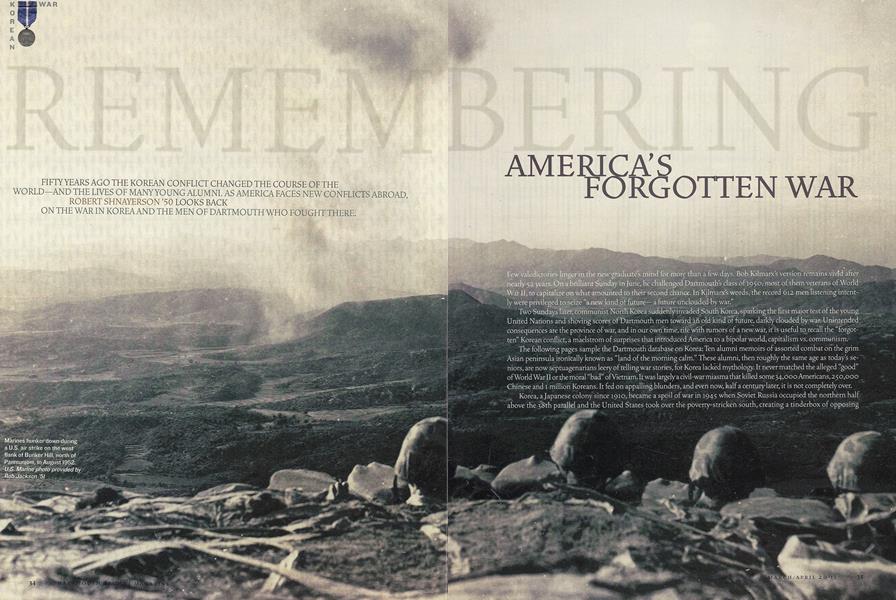

Mar/Apr 2003 ROBERT SHNAYERSON ’50FIFTYYEARS AGO THE KOREAN CONFLICT CHANGED THE COURSE OF THE WORLD AND THE LIVES OF MANY YOUNG ALUMNI. AS AMERICA FACES NEW CONFLICTS ABROAD, ROBERT SHNAYERSON '50 LOOKS BACK ON THE WAR IN KOREA AND THE MEN OF DARTMOUTH WHO FOUGHT THERE.

Few Valedictories linger in the new graduate's mind for more than a few days, Bob Kilmarx's version remains vivid after nearly'52 years. On a brilliant Sunday in June, he challenged Dartmouth's class of 1950, most of them veterans of' World War II, to capitalize on what amounted to their second chance. In Kilmarx's words, the record 612 men listening intently were privileged to seize "a new kind of future-a future unclouded by war."

Two Sundays later, communist North Korea suddenly invaded South Korea, sparking the first major test of the young United Nations and shoving scores of Dartmouth men toward an old kind of future, darkly clouded by war. Unintended consequences are the province of war, and in our own time, rife with rumors of a new war, it is useful to recall the "forgotten" Korean conflict, a maelstrom of surprises that introduced America to a bipolar world, capitalism vs. communism.

The following pages sample the Dartmouth database on Korea: Ten alumni memoirs of assorted combat on the grim Asian peninsula ironically known as "land of the morning calm." These alumni, then roughly the same age as today's seniors, are now septuagenarians leery of telling war stories, for Korea lacked mythology. It never matched the alleged "good" of World War II or the moral "bad" of Vietnam.It was largely a civil-war miasma that killed some 34,000 Americans, 250,000 Chinese and 1 million Koreans. It fed on appalling blunders, and even now, half a century later, it is not completely over.

Korea, a Japanese colony since 1910, became a spoil of war in 1945 when Soviet Russia occupied; the northern half above the 38th parallel and the United States took over the poverty-stricken south, creating a tinderbox of opposing interests. Russia's Joseph Stalin turned the north into a Soviet satellite run by the dictator Kim II Sung, who was, in his own words, "a matchless iron-willed commander who is ever-victorious." Compounding this witch's brew was the communist takeover of nearby China in 1948, an event that incited U.S. right-wingers to accuse the Truman administration of "losing China" by harboring procommunists in the foreign service.

In January 1950 Harry Truman's Secretary of State, Dean Acheson, outlined Americas Pacific defense perimeter in a famous speech to the National Press Club. The line defended U.S.-occupied Japan and relied on sea power to limit communism to the Asian mainland. Speaking for the president, who wanted no part of any Asian ground war, Acheson fatefully excluded South Korea from the U.S. perimeter.

Stalin apparently saw an opportunity: By unleashing Kim II Sung for a limited attack on South Korea, he could provoke war fears in the region and worry communist China into becoming a grateful client dependent on Soviet military power. But Stalin misjudged three things: Sung's belligerence, Americas response and Chinas malleability.

Sung launched a far bigger war than Stalin probably intended. America made it a United Nations war, and China used it to become a front-rank military power that didn't have to rely on Soviet might. In the ultimate irony, the Korean war triggered a bipolar arms race with at least one good result: In time it forced the Soviet Union to spend itself out of existence.

INVITING INVASION

In 1950 the North Korean People's Army was formidable. The Russians had armed Sung with myriad toys: eight good infantry divisions, 120 T-34 tanks, heavy howitzers and 180 modern planes, including 40 Yak fighters. By contrast, the Republic of Korea had 12 unarmed planes, no tanks and no heavy artillery. Moreover, the United States had slashed its post-war armed forces by a factor of 13 since 1945 and had not drafted anybody since 1947. Stalin now had 260 divisions; America had a puny peacetime army, much of it the four under-strength divisions stationed in Japan. It was still the world's only nuclear power, but it no longer had a single atomic bomb in stock.

Given these inviting circumstances, Sung's 135,000 invaders cut through the Souths 98,000 defenders like butter, captured the capital city of Seoul and within days controlled half the republic, driving its reeling forces into the country's southeast corner around Pusan.

Harry Truman saw the invasion as step one of an attack on Japan. At home he could ill afford the loss of "another China," raw meat for Republicans who scorned him as a "little man" unworthy of his landslide election in 1948. Truman acted with the dispatch that eventually marked his presidency. He redrew the U.S. defense perimeter to include Korea. And instead of asking Congress to declare war, he sought "moral authority" from the United Nations to launch a "police action" against North Korea.

The United States persuaded the U.N. Security Council (then blessed by a Soviet boycott) to brand the North Koreans as aggressors and call on member states for military help. Some 16 countries answered the call, among them Australia, Britain, Canada, Colombia and Turkey. But Americans ran the war.

MACARTHUR vs. EISENHOWER

The first U.S./U.N. force on the scene faced disaster. Rushed from Japan, Major General William F. Deans green 24th Infantry Division rapidly lost 30 percent of its combat troops and much equipment. Dean himself was ambushed while stalking tanks with a bazooka; he spent the next three years as a North Korean prisoner.

By August 1950 the North Koreans seemed on the brink of driving U.S. troops off the peninsula, but U.S. pilots and sailors soon achieved total command of the air and sea, opening the way to General Douglas Mac Arthur's fabled masterstroke—the mid-September landing of two divisions by sea at the port of Inchon, 150 miles behind enemy lines. Cut off and heavily bombed, the North Koreans fled back north, inspiring MacArthur to order hot pursuit across the 38 th parallel, deep into North Korea and well on the way to Chinas Manchurian border.

Unintended consequences loomed again. That Mac Arthur had been seduced by his enormous ego was rapidly confirmed, first by his boast that the war would be "over by Christmas," and second by his utter surprise at the predictable glitch. Far from appealing to Stalin, who had already lost control of his North Korean caper. Communist China suddenly defended its territory by pouring 300,000 seasoned troops into Korea, driving the U.N. forces southward in subzero weather, a harrowing winter retreat featuring epic ordeals such as the Ist Marine Divisions stand against six Chinese divisions at the Chosin Reservoir. By January 1951 U.N. forces were defending a line considerably south of Seoul.

In April the Chinese launched a savage spring offensive, but the U.N. line held and slowly moved forward again, this time with no foolhardy rush north. And this time without Douglas MacArthur.

The nations foremost military hero, an honorific he would not consider immodest, had tarnished his glamour in March. When Truman suggested that the time had come to negotiate peace in Korea, Mac Arthur quickly one-upped the president. He issued a public statement that he stood ready not only to handle such negotiations, but also to invade Communist China, which he claimed would rapidly collapse upon his arrival. Truman was incensed. He fired Mac Arthur for what he considered a blatant affront to civilian control of the military. The general's subsequent don't-blame-me speech to Congress was worthy of a 19th-century Shakespearean actor, especially his throaty last line: "Old soldiers never die, they just fade away."

The war did not fade away. Vicious fighting persisted for the next two years as both sides made small advances and retreats, trying to dominate a line roughly along the 38th parallel. Armistice talks finally began in 1951 but stalled when thousands of the Souths communist prisoners refused to be repatriated and the North demanded their return. It remained to a very different kind of American general, Dwight Eisenhower, to force through a truce.

As the Republican presidential candidate in 1952,, Ike perceived that Americas frustration over the Korean war had enabled political opportunists, notably Senator Joseph McCarthy, to manipulate the country's fears of subversion in high places. Ike promised, "I shall go to Korea," and beat Adlai Stevenson by a landslide. As president, he did go to Korea, backed a plan for partitioning the peninsula and overcame the foot-dragging of Syngman Rhee, the Souths autocratic president, who had long envisioned himself ruling the entire country. The armistice signed on July 27,1953, brought calm if not quite peace, secured by a U.S. military presence that has lasted decades beyond the heyday of McCarthy, who ran out of political gas soon after Korea disappeared from the headlines.

CLASS WARFARE

Those tumultuous events yanked Dartmouth students out of a campus bubble that made Bob Kilmarx's valedictory perfect for graduation day, june 11,1950, and pretty much toast two weeks later.

Arriving in 1946, the huge post-war class had no parallels before or after. That fall Hanover was divided between freshman veterans wearing military castoffs and those a mere birthday or so younger who seemed to envy their elders for having experienced some mystical rite of passage. Hallowed campus customs did not survive. The freshman tug of war was laughed off the Green. Perhaps six freshmen heads sported beanies. Dartmouth drinking soared, but so did the proportion of students able to hold their liquor. Strange times.

Both groups soon merged peacefully enough, bewitched by brilliant foliage, bright snowscapes and a somewhat dazed America on leave from great-power pressures, blissfully unaware that its escape was only temporary.

The nation then consisted of 150 million Americans, a little over half the current population. The cultural milestones of the day ranged from South Pacific to Death of a Salesman; from Orwell's 1984 to Salinger's Catcher in the Rye; from Charles Shulz's Peanuts cartoons to Jackson Pollock's drip paintings. Scientific breakthroughs included Salk's polio vaccine, the first mass-produced computer, the structure of DNA and the hydrogen bomb. The Yankees won the World Series five years in a row, and Dartmouth was the equivalent powerhouse in college hockey.

Thanks to the "Great Issues" course, a splendid innovation of the day, Dartmouth seniors were more worldly wise than many other Ivy Leaguers. "G.I." imported a river of outside speakers to brief students on key concerns. One evening you could hear Senator William Fulbright's acerbic views of his demagogic colleague Joe McCarthy. Another evening it might be historian Arthur Schlesinger pondering the duties of the modern state. The briefers included diplomats, governors, theologians and civil-rights lawyers. They discussed everything from Asian power politics to certain parallels between religion and fascism.

Even so, Korea was hardly the graduation present anybody expected. Those in the ROTC units had mainly joined for reasons such as avoiding the reactivated draft, not to suddenly become Marine shavetails or Navy ensigns. Still, war tends to excite young men, especially those entrusted with incredible machines such as menacing destroyers or sleek fighter planes. For those who hadn't been in the big war, Korea was a credible cause and a chance to share a singular experience. Enthusiasm trumped fear. There was a rush to sign up, even among those who weren't good at machinery or had to memorize the eye chart to get into Officer Candidate School.

Some early losses ensued. One of the first was Alan Tarr '50, an Exeter graduate and a brilliant actor whose performances in TheGlass Menagerie and other campus productions made him president of the Dartmouth Players and gave the class of 1950 a special glow. Tarr seemed born to master emotions rather than, say, machines. He was quite possibly a future Richard Burton, one of those charismatic classmates you know the world will be lionizing in 10 years. Instead, he joined the Air Force and learned to fly fighter planes. People in his squadron apparently admired his skill. But he had been in Korea only a few weeks when his F-84 spun out of control and crashed into the sea. He was 24.

Most of Dartmouth's Korean veterans seem to have few regrets. They speak hauntingly of the massive casualties on both sides, and, given the Vietnam mess on top of Korea, they have no interest in another Asian land war anytime soon. But time is a great editor; at this remove, the positives survive. In Korea, the veterans note, the United Nations trumped the old League of Nations by backing collective action to stop aggression for the first time. The United States itself took a giant step toward global superpower, for good or ill. The war enabled South Korea to leap from poverty to prosperity as a freemarket democracy. And though the North hangs on with a cruel despot pursuing nuclear arms, the country is so desperately poor that its tough talk may be as much a pitch for aid as a serious threat. North Korea is evil, yes, but Iraq is something else.

Half a century later, our Korean War alumni say the experience changed their lives, not necessarily for the worse.

Howie Weston '50 joined the Air Force because, "I was draft bait and didn't want to be a grunt." He flew 100 missions in F-86s, the first sweptwing jet fighters, mainly escorting bombers and photo reconnaisance planes. "I broke even," he says. "I didn't kill anybody and nobody killed me." In fact, he liked flying so much that he spent his next2s or so years working for TWA. If he has any advice for today's college seniors, Weston says, it's simple: "Don't count on anything. This week's world won't be next week's world. Keep an open mind. And if you get a chance to go into the military, don't dread it. Take it. Have fun. It was better than I ever expected."

Gene Carver '50 says he especially valued the Army's leadership training and his early exposure to racial integration, which the Army was just then pioneering. Carver spent his Korean year as a first lieutenant nursing 155 mm howitzers for the 3rd Infantry Division. He particularly remembers the night of the armistice in 1953 because one of his big guns accidentally went off after the deadline, causing fears the war had resumed.

Carver came home intact to a successful career as a mortgage banker in the Pacific Northwest; he retired in 1998. He thinks todays students need to be much better informed about the real world that often escapes their attention. If he could address the class of 2003, he would implore them to stay open-minded and allergic to conventional wisdom. "Listen to more than TV sound bites," he says. "Read and keep reading. Read past the headlines. Read conflicting books and periodicals. Understand opinions you don't agree with. Look over the edge.Think for yourself...think."

Marines hunker down during a U.S. air strike on the west flank of Bunker Hill, north of Panmunjom, in August 1952. U.S. Marine photo provided byRob Jackson '51

KOREAWAS HARDLY THE GRADUATION PRESENT ANYBODY EXPECTED. STILL, ENTHUSIASM TRUMPED FEAR, AND THERESAS A RUSH TO SIGN UP

"I BROKE EVEN" SAYS AIR FORCE PILOT HOWIE AND NOBODY KILLED ME." WESTON '50. "I DIDN'T KILL ANYBODY

Clockwise from top right: Richard Paul '44 (right) with a Korean colonel at Sojol-li command post in February 1951; Hank Fry '53 teaches a mapping class to MPs near the 38th parallel; Korean laborers carry supplies up a road created by U.S. engineers, including Buck Scott '51: Whitey Hand '51 and Henry Nachman '51 of the 5th Regimental Combat Team in June 1953; Robert Myers '50 aboard the USS John A. Bole; 50-caliber truck-mounted machine guns photographed at the front by Scott; Fry's winter home of 1954 ("It was like a small dormitory," he says); a Scott photo of a pontoon bridge used for ferrying tanks and supplies at Hwachon Reservoir.

BOB SHNAYERSON did not go to Korea, having already done his bit in theNavy during World War II, but many of his classmates did. Shnayerson spentsubsequent years as a magazine editor (Time, Life, Harper's, Quest) andfathering Dartmouth students Michael '76 and Maggie '03.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWomen on the Verge

March | April 2003 By Jennifer Kay ’01 -

Feature

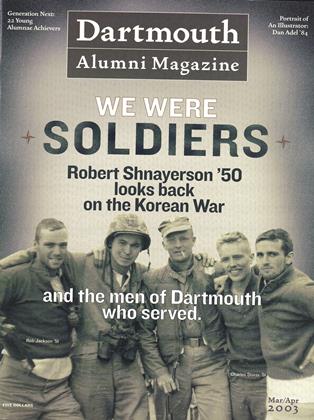

FeatureWe Were Soldiers

March | April 2003 By CASEY NOGA '00 -

Feature

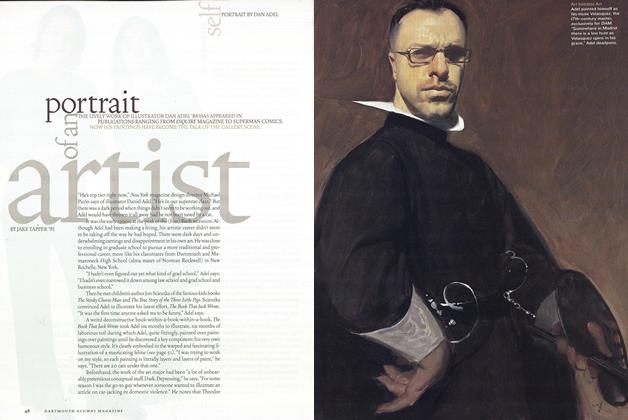

FeaturePortrait of an Artist

March | April 2003 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Alumni Opinion

Alumni OpinionLoaded Canon

March | April 2003 By Dinesh D’Souza ’83 -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

March | April 2003 By MIKE MAHONEY '92 -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionThe Cost of Winning

March | April 2003 By Professor Ray Hall

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryRIDE of a LIFETIME

May/June 2013 -

Feature

FeatureHigh On Your Dial

December 1975 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

FeatureThe Fated Morning

FEBRUARY 1964 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21 -

COVER STORY

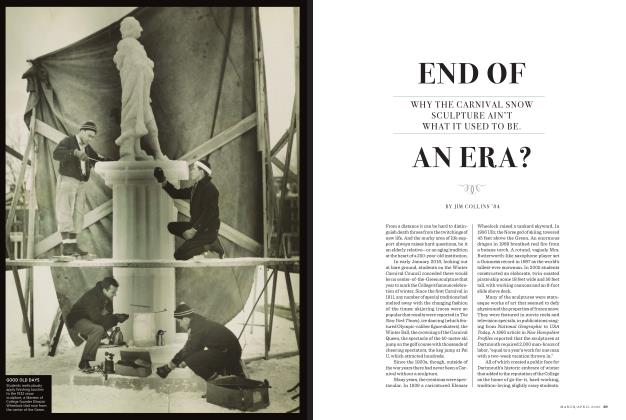

COVER STORYEnd of an Era?

MARCH | APRIL 2020 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

Feature

FeatureThe Day I Got Chewed Out By Red Blaik

NOVEMBER 1989 By Rodger S. Harrison '39 -

Feature

FeatureTesting the Body's Competitiveness

NOVEMBER • 1987 By Teri Allbright