Portrait of an Artist

The lively work of illustrator Dan Adel ’84 has appeared in publications ranging from Esquire magazine to Superman comics. Now his paintings have become the talk of the gallery scene.

Mar/Apr 2003 Jake Tapper ’91The lively work of illustrator Dan Adel ’84 has appeared in publications ranging from Esquire magazine to Superman comics. Now his paintings have become the talk of the gallery scene.

Mar/Apr 2003 Jake Tapper ’91THE LIVELY WORK OF ILLUSTRATOR DAN ADEL '84 HAS APPEARED IN PUBLICATIONS RANGING FROM ESQUIRE MAGAZINE TO SUPERMAN COMICS. NOW HIS PAINTINGS HAVE BECOME THE TALK OF THE GALLERY SCENE.

"He's top tier right now," New York magazine design director Michael I Picon says of illustrator Daniel Adel. "He's in our superstar class." But there was a dark period when things didn't seem to be worki ng out, and Adel would have thrown it all away had he not been saved by a cat.

It was the early 1990s, at the peak of the (first) Bush recession. Although Adel had been making a living, his artistic career didn't seem to be taking off the way he had hoped. There were dark days and underwhelming earnings and disappointment in his own art. Hewas close to enrolling in graduate school to pursue a more traditional and professional career, more like his classmates from Dartmouth and Mamaroneck High School (alma mater of Norman Rockwell) in New Rochelle, New York.

"I hadn't even figured out yet what kind of grad school," Adel says. "I hadn't even narrowed it down among law school and grad school and business school."

Then he met children's author Jon Scieszka of the famous kids books The Stinky Cheese Man and The True Story of the Three Little Pigs. Scieszka convinced Adel to illustrate his latest effort, The Book That Jack Wrote. "It was the first time anyone asked me to be funny," Adel says.

A weird deconstructive book-within-a-book-within-a-book, TheBook That Jack Wrote took Adel six months to illustrate, six months of laborious toil during which Adel, quite fittingly, painted over paintings over paintings until he discovered a key component: his very own humorous style. It's clearly embodied in the warped and fascinating illustration of a masticating feline (see page 51). "I was trying to work on my style, so each painting is literally layers and layers of paint," he says. "There are 20 cats under that one."

Beforehand, the work of the art major had been "a lot of unbearably pretentious conceptual stuff. Dark. Depressing," he says. "For some reason I was the go-to guy whenever someone wanted to illustrate an article on car-jacking or domestic violence." He notes that Theodor Geisel '25 went through a similar process to find his proper muse, "not to suggest more than a passing parallel to the great Dr. Seuss."

From the book—and that cat, to a degree—came a lot. "I'm sure it's done some serious psychological damage to at least a handful of kids," Adel chuckles. Well, that too, but also awards and notice and a contract with Esquire, which led to a contract with Vanity Fair and work for Entertainment Weekly and a portrait of Madonna as The Empress for Steven Spielberg's Starbright book project and on and on. And money. And an apartment in Phillip Roth's building and a studio in lower Manhattan. And work! And happiness with work. And variety—such as the cover Adel did for the March 2002 comic book, The Adventures of Superman. His work has also appeared in Dartmouth Alumni Magazine. But it's not just illustrations anymore—Adel regularly receives commissions to paint private portraits.

And of course—finally—the exhibit. Last November 7, Adel was the man of the hour at the Arcadia Fine Arts gallery in Soho. Among 30 majestic still-life oil paintings of crumpled paper and swooping sheets—some on sale for upwards of $27,000—Adel looked like the cat that ate the canary. Bohemians mixed with Upper East Siders, family members kvelled while sophisticates furrowed their brows.

All of this because of a cat. And he doesn't even like cats. He's allergic. Which, in Adel's life, makes a perfect kind of sense.

Adel sits in his studio and takes a long draw on a Marlboro Red. He's almost 40—it shows in his graying, slightly receding hairbut he bubbles with a certain hipster youth. Short and trim, he wears the official bohemian Manhattan black. His voice twangs perhaps a bit consciously, not unlike Christian Slaters.

On his desk is a sketch he's working on that few will ever see. The Sopranos is preparing a new ad campaign featuring the angst-ridden HBO crime family in Hell. Celebrity photographer Annie Leibovitz will take the pictures, but before the studio time can commence, she needs to sell show creator David Chase on the concept. He can't see it. So Leibovitz hired Adel to help explain it. Great as Leibovitz is, there's a lot to be said for simply using Adel's painting in the ad campaign. His caricatures live in a netherworld between reality and just off of reality, the way dear friends and enemies start to appear late nights, illuminated by neon and fuzzed by abused substances. Leibovitz will no doubt have fun capturing actor James Gandolfini. Adel would capture his character, Tony Soprano.

On his easel is art for a Newsweek cover, a tribute to three prominent African-American CEOs. His studio is neat, in a messy kind of way. Brushes, many brushes. Pieces of statues. Glossy magazines, stained by drinks and ash. A copy of Alexis de Tocqueville's Democracy in America.

On the wall is a piece from his exhibit, a painting of a swirling canopy, billowing upward in a spiral as if the Venus it cloaked had just been snatched. Two models of another subject—a carburetor removed from an engine—sit on the floor nearby.

"I could never bear to paint fruit and flowers," Adel says. "Somehow, tulips don't say anything about late-20th-century, early-21st-century America. We're not really about tulips anymore."

About 20 samples of the work he's best known for peer from the walls. From The New Yorker: a perverse, slobbering Ken Starr byway of Victor Hugo—with a quill scribbling furiously, frantically, angrily. You'can almost smell those infamous Starr Report footnotes. Then there's boxer George Foreman grilling himself on his late-night-infomercial product The Grillmaster, done for Men's Health. From comes a monster-sized Anna Nicole Smith with teeny workers primping, sculpting, constructing her from the scaffolding she already so generously provides. There's also an "I Want You" portrait of Rudy Giuliani from New York magazine, which appeared in the wake of September 11.

Adel's girlfriend had called him that fateful morning. She lived three blocks from the towers. People were fleeing in the streets and she couldn't figure out why; her TV wasn't working. At home—free-lance hours: Adel sleeps to about 10 a.m.; he returns home from work at around 3 a.m.—the artist turned on his TV. "Get the hell out of there!" he commanded her. He also advised her to take the dog but leave behind her fat cat, to whom he is allergic. She fled, ignoring his advice about the cat.

A letter from Henry Kissinger hangs from Adel's wall, requesting a Weekly Standard cover he painted. The former Secretary of State writes that he "didn't like the review" of his book done in the Standard, but he "loved the cover. Could I have the original?"

Dense and almost Baroque (the painter seems to owe more to Caravaggio than Levine), Adel's caricatures aren't particularly mean. "I'm a fairly kindly satirist," he admits. He says he's only offended one of his subjects, the comic writer Jack Handey, whom Adel liked when he met and whom he thought he was flattering by cleaning up his flawed choppers. 'At no extra charge, I gave him major orthodontia," says Adel. "Lightening, caps—the works!" Handey didn't think so; the editors of Texas Monthly, which commissioned the piece, received a nasty note written on his lawyer's stationery.

Adel remains bewildered to this day. (And disappointed, too, as he liked Handey and seems to share his appreciation for the absurd.) The caricature is rather benign; Handey zooms along a highway, two of his Saturday Night Live creations—Toonses the Driving Cat and the Unfrozen Caveman Lawyer—by his side. If Handey is truly as goofy-looking as Adel attests, the artist did in fact do him a favor.

But Handey is an exception. Rich folk—the most recent being New York chief judge-turned-jailbird Sol Wachtler—regularly ask Adel to capture them in portraiture, which he says was his first love." He does two or three a year; one took a few weeks to finish, another remained in his studio as a work-in-progress for five and a half years. The best wall space-in his studio belongs to a portrait of his grandfather that Adel did for his mother; his grandfather died soon after it was finished. It's a lovely picture: serious, stern, respectful. He's wearing a hat.

"The first drawings I did as a kid that I really remember getting a thrill out of were the portraits," Adel says. His first published art of any sort was the cover of the program for his elementary school production of The Tempest, but he pooh-poohs it as a rush job composed of waves and "abstract garbage." Adel 'took mostly art history classes at Dartmouth. He seems to feel that he was coasting back then. After salad days and time putting himself through four years at the National Academy of Design in Manhattan, where he learned to paint, he is no longer apologetic.

Nor is Adel under any delusions. "I know I'm in the midst of my heyday as an illustrator," he says. He knows how it works. He's hot now, but "in a few years I'll begin my slow decline." New York's Picon agrees that the business is fickle, but notes that people come back. "Dan's lucky in that he does portraiture, and there's never gonna be a lack for portraiture."

Still, the capricious whims of publishing may be one of the reasons for his diverse portfolio—the illustrations, the portraits and the work for his show in Soho—though Adel says he enjoys being able to do all three and that the variety keeps him interested. The non-studio work also enables him to deal with other human beings. "I don't think I could paint in solitude fulltime without becoming a complete freak," he says. Plus it's not bad to have stuff in popular magazines. "It's nice to be out there participating in what is essentially journalistic discourse. And of course no one likes to labor in obscurity.""Artists in the past enjoyed lives of more community than today, he says.

"[French artist Adolphe-William] Bouguereau had an entire family of naked Italians living with him" as models, Adel says by way of contrast. Pause. "I've tried to find a family of naked Italians for myself, but for some reason they're hard to find."

The night has fallen and Adel's girlfriend calls to see when he's coming home. We're wrapping it up, I assure him Just tell me which of all these paintings is your favorite—a question that almost all authors and artists will beg off lazily, annoyingly comparing their work to their equally beloved children. But not Adel.

"I'm pretty sentimental about that cat,' he says. He points up to it. It's still grinning contentedly, creepily, a rat's tail hanging from its mouth like linguini about to be slurped. All that paint underneath the cat is starting to bubble.

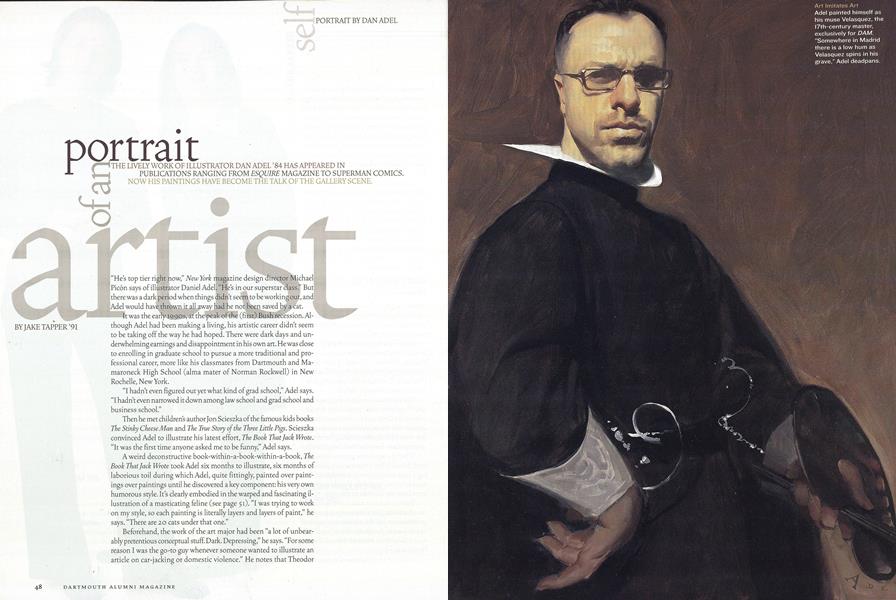

Art Imitates Art Adel painted himself as his muse Velasquez, the 17th-century master, exclusively for DAM. "Somewhere in Madrid there is a low hum as Velasquez spins in his grave," Adel deadpans.

DRAPERY #5(2002), FROM ADEL'S RECENT NEW YORK SHOW. OPPOSITE: THE CAT FROM THE BOOKTHAT JACK WROTE, HUGH GRANT FOR ESQUIRE, GEORGE W. BUSH FOR BUSINESSWEEK.

"I COULD NEVER BEAR SOMEHOW, TULIPS DON'T WE'RE NOT REALLY O PAINT fruit and flowers. AY ANYTHING ABOUT 21ST-CENTURY AMERICA. BOUT TULIPS ANYMORE."

JAKE TAPPER is national correspondent for Salon.com. Dan Adel's Website is www.danieladel.com.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWomen on the Verge

March | April 2003 By Jennifer Kay ’01 -

Feature

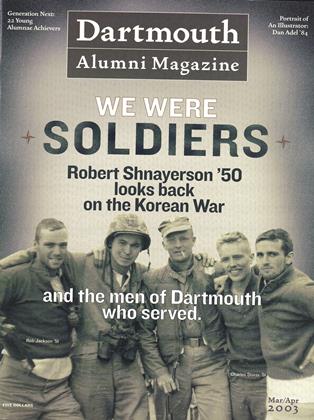

FeatureWe Were Soldiers

March | April 2003 By CASEY NOGA '00 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryRemembering America’s Forgotten War

March | April 2003 By ROBERT SHNAYERSON ’50 -

Alumni Opinion

Alumni OpinionLoaded Canon

March | April 2003 By Dinesh D’Souza ’83 -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

March | April 2003 By MIKE MAHONEY '92 -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionThe Cost of Winning

March | April 2003 By Professor Ray Hall

Jake Tapper ’91

-

Cover Story

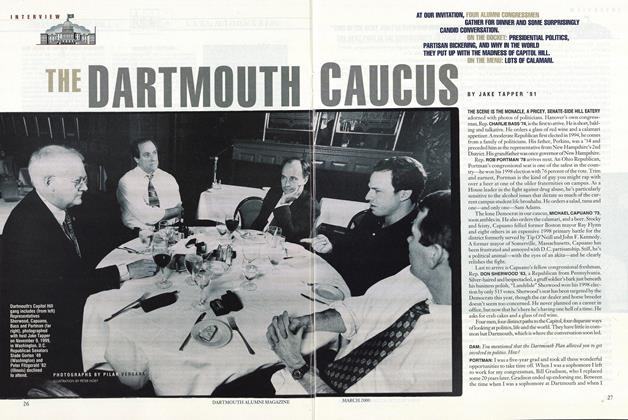

Cover StoryThe Dartmouth Caucus

MARCH 2000 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Feature

FeaturePolitical Junkie

Nov/Dec 2000 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Feature

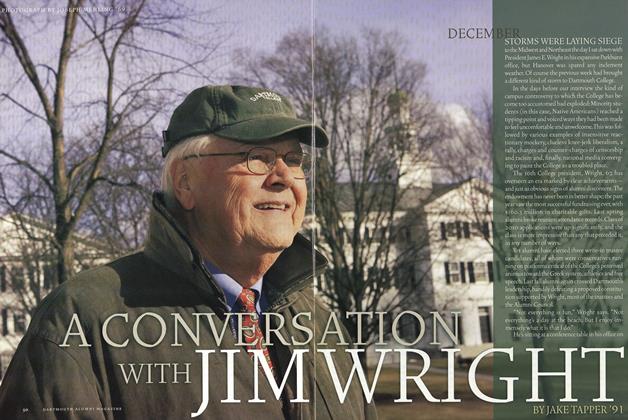

FeatureA Conversation With Jim Wright

Mar/Apr 2007 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

THE DAM INTERVIEW

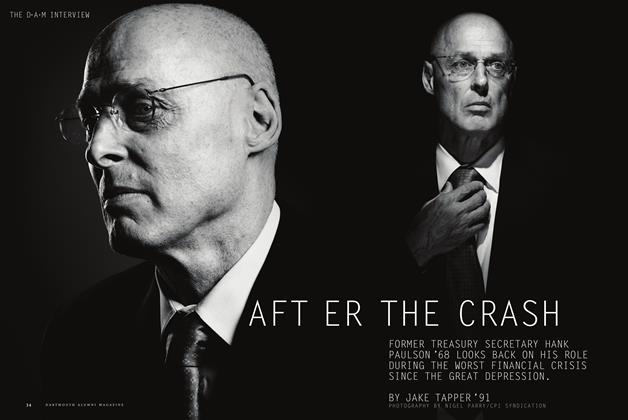

THE DAM INTERVIEWAfter the Crash

Mar/Apr 2010 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Cover Story

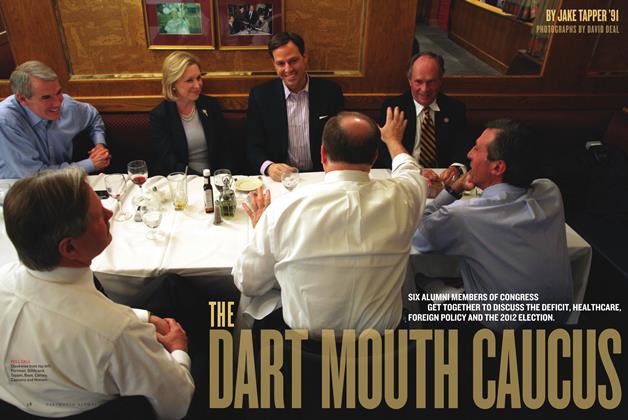

Cover StoryThe Dartmouth Caucus

July/August 2011 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

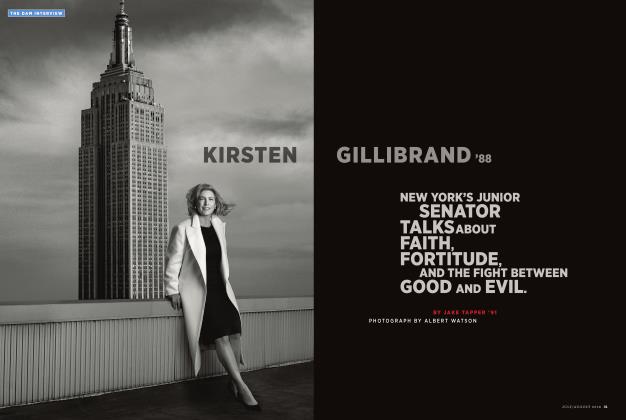

The DAM Interview

The DAM InterviewKirsten Gillibrand ’88

JULY | AUGUST 2018 By Jake Tapper ’91

Features

-

Feature

FeatureKappa Kappa Grandpa

MAY 1985 By Gabrielle Guise '85 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO BUY A BETTER TWO-BY-FOUR

Sept/Oct 2001 By HERBERT KATZ '52 -

COVER STORY

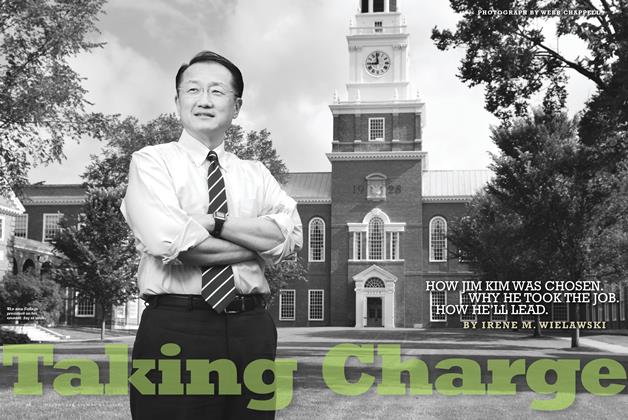

COVER STORYTaking Charge

Sept/Oct 2009 By Irene M. Wielawski -

Feature

FeatureIt's Where We're Coming From, Citizens

November 1979 By Jeffrey Hart -

Feature

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT 1972

JULY 1972 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Feature

FeatureThe Affirming Flame

May/June 2003 By SUSAN DENTZER ’77