The Cost of Winning

From brawls to brushbacks, violence in sports sets a dangerous example for the nation’s youth.

Mar/Apr 2003 Professor Ray HallFrom brawls to brushbacks, violence in sports sets a dangerous example for the nation’s youth.

Mar/Apr 2003 Professor Ray HallFrom brawls to brushbacks, violence in sports sets a dangerous example for the nations youth.

VIOLENCE HAS LONG BEEN A growth industry in American society. This is especially true in sports today, from school playgrounds to collegiate and professional sports arenas. Violence in sports used to be taken for granted, but recently excessive intimidation, aggression, fighting, assaults, injuries and even death have catapulted gratuitous sports violence into a major societal concern.

Curbing sports violence is an uphill battle. Turn on ESPN any time to witness violence packaged as game highlights: brushback pitches and team brawls on the diamond, taunting and helmet-throwing on the gridiron, bloody cross-checking on the ice, intentional fouls on the basketball court. Long pervasive in male sports, such violence is escalating at nearly all levels of female sports, too. Women's basketball, ice and field hockey and soccer, among others, are becoming more and more "physical" (read: violent).

A crucial concern surrounding violence in sports—both men's and women's—is its impact on children. Some 25 to 30 million youngsters between the ages of 6 and 16 participate in formal sport programs. These activities provide one of the most important socialization experiences these youth will encounter. Public opinion on youth sports is divided precisely because of the potential psychological, social and physical effects organized sports may have on children. One side argues that competitive sports are detrimental to the healthy development of children, while the other believes that early socialization into competitive sports provides children with an advantage in highly competitive American society. There is general agreement, however, that violence in adult sports has a negative impact on youth sports.

It must not be forgotten that violence

is an integral part of Western sports culture and thus not new to American society. While the Roman Colosseum conjures up the most infamous form of Western sports violence, in ancient Greece it was legal to kill a man for entertainment purposes. Even in this country today, if a person is killed in the playing of a game or sport, it is regarded as unfortunate but not a criminal offense.

Contemporary concern with sports violence should be seen against the backdrop of prevailing explanations of sports. For-quite some time athletics have been seen as constructive and healthy expressions of energy, including aggressive energy. In this view, sports build character, instill respect for authority and promote discipline and perseverance, enhancing individual success in later life. This perspective on sports stems from the drivedischarge hypothesis in evolutionary

biology that humans are programmed for aggression because it serves speciesmaintaining and species-preserving functions. Psychological theory suggests that when an obstacle blocks efforts to achieve a goal, aggression is often utilized to overcome frustration. The frustrationaggression hypothesis continues to be used to explain individual acts of violence in sports.

Competing explanations include social learning theory, which argues that human behavior, aggressive and otherwise, is learned through reward and punishment. If violent behavior in sport—as in society at large—is reinforced with monetary or social rewards (praise, recognition or awards) the rewarded behavior will increase in frequency—and perhaps in intensity. Youngsters quickly learn that aggression earns reward, not punishment.

What to do to stem the tide of violence in sports? There is no easy solution. Sports operate in a different world, where aggression is part of the game, and violence resulting from competition and aggression tends to be "within the rules" of competition.

The legal system has been less than definitive on sports violence. No specialized sports law exists. While some argue that laws should define acceptable levels of violence and establish fair and consistent consequences, we are not there yet.

One response to sports violence fo- cuses on reducing or eliminating rules, regulations and conventions that contribute to violence and injuries. The National Hockey League has initiated steps

to reduce fighting. The commissioner of the National Basketball Association levies heavy fines on and often suspends individuals involved in altercations. Baseball has cracked down on deliberate brushback pitches. Professional football, intrinsically violent as a contact sport, has nonetheless initiated several rules, including the outlawing of taunting, geared to protect excessive aggression, especially against vulnerable quarterbacks and wide receivers. Unfortunately, these efforts have not gained widespread public support. The sad truth is that many fans like sports violence.

What of violence in school sports? I know coaches who stress nonviolence and take drastic corrective measures if a player violates this ethic. (As a proud parent of a daughter who plays Division I basketball, I would take drastic measures, with the coach if he condoned gratuitous violence in the pursuit of winning!) Unfortunately, the ethic of winning at all costs is alive and well in sports, among both coaches and parents. Not only are youngsters egged on by coaches to win by any means necessary, but losing exposes the children to reproach from their parents.

Some argue that support for sports violence rests outside the athletic arena. Some blame the media, particularly television, with promoting sports violence. With the use of instant replay, a violent or unnecessarily aggressive play can be seen over and over by more people than ever before. (Dare we wonder what impact the monstrous violence heaped on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon September 11, shown over and over by the visual media, will have on youngsters' views of violence in general?) Others blame the violent nature of American society. As noted sports sociologist Jay Coakley put it in 1999: "Historically, the very freedom most Americans enjoy grew out of violence." Moreover, sports aggression is intimately connected with a number of core American values, such as individualism, competition, hard work and success, all of which are keys to upward mobility.

Johan Huizinga, the renowned Dutch historian, warned nearly 70 years ago in his book Homo Ludens that to allow the play element of sport and culture to be displaced by violence diminishes our humanity. We must never lose sight of the potential impact that violence—including aggressive sports—is having on young people. Clearly it is yet another source of violence to which American youngsters are exposed. Instances such as the Columbine shooting and the numerous other outbreaks of unspeakable youth violence in and outside schools remind us that something is desperately out of kilter when youngsters are continuing the tradition of violence that has too long possessed American society.

Fortunately, awareness is afoot. Americans are beginning to see sports violence for what it is—deviant behavior—rather than an acceptable part of the game.

Egged on by coaches, youngsters quickly learn that aggression earns reward, not punishment.

RAY HALL is a sociology professor who teaches a course on the sociology of sports.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWomen on the Verge

March | April 2003 By Jennifer Kay ’01 -

Feature

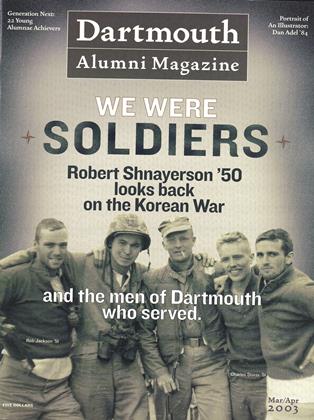

FeatureWe Were Soldiers

March | April 2003 By CASEY NOGA '00 -

Cover Story

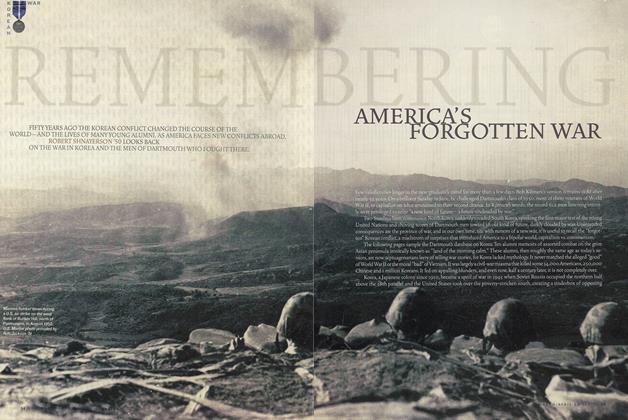

Cover StoryRemembering America’s Forgotten War

March | April 2003 By ROBERT SHNAYERSON ’50 -

Feature

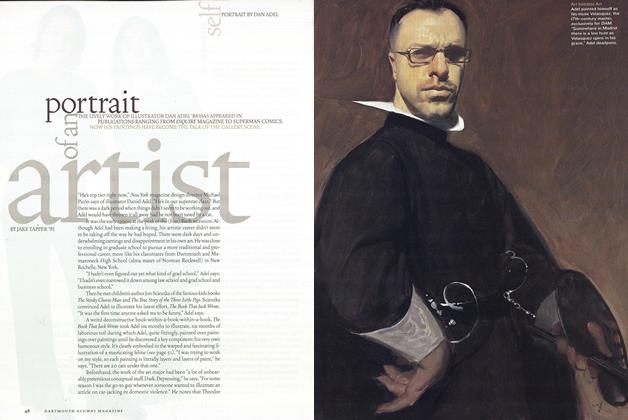

FeaturePortrait of an Artist

March | April 2003 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Alumni Opinion

Alumni OpinionLoaded Canon

March | April 2003 By Dinesh D’Souza ’83 -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

March | April 2003 By MIKE MAHONEY '92

Faculty Opinion

-

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONEggheads vs. Meatheads?

Nov/Dec 2005 By DAVID KANG AND ALLAN STAM -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONSlow Medicine

May/June 2009 By Dennis McCullough, M.D. -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONA Well-Traveled Story

July/Aug 2009 By Ernest Hebert -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONA Sorry State of Affairs

Jan/Feb 2008 By Jennifer Lind -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONSpeaking in Tongues

May/June 2006 By John Rassias ’49A, ’76A -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionWater Under Fire

July/August 2001 By Joshua Hamilton