QUOTE/UNQUOTE "A full liberal arts education for our teachers is the best kind of homeland security for the long ran." HISTORIAN DAVID McCULLOUGH, SPEAKING AT COMMENCEMENT ON JUNE 8

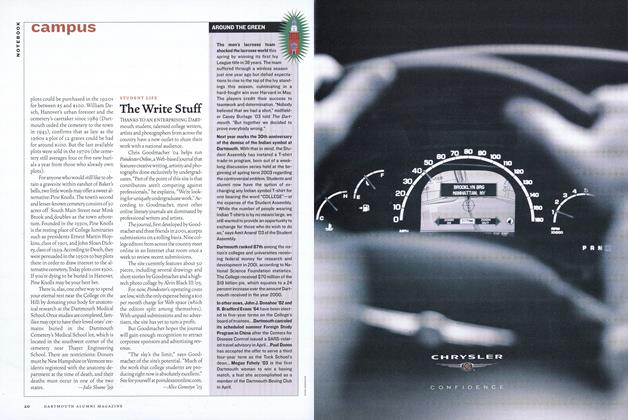

Last fall Kellen Haak '79, Collections manager for the Hood Museum of Art, ventured to Angoon, a small Alaskan fishing village, to return a rare ceremonial tunic to its Native residents. After 43 years at the Hood, the tunic was reunited with its original owners—for good.

The tunics long journey home was the culmination of years of research on Haak's part. In 1990 Congress mandated that Native American ceremonical objects housed in museums be returned to the tribes from which they'd come. Shortly thereafter, Haak gave himself the additional title of repatriation coordinator and set out to take stock of the thousands of Native American items at the Hood—many with uncertain histories. In 1995 Haak secured a grant from the National Park Service to bring a delegation of representatives from several Alaskan tribes, known collectively as the Tlingit, to Dartmouth to take a look at the Hoods collection firsthand.

Among the visitors was Matthew Fred, a Tlingit elder from Angoon, who made an exciting discovery. He recognized a canary-yellow tunic as the stuff of legends—a ceremonial object that once belonged to his ancestors, members of Angoons Kootznoowoo tribe. It had been missing for more than half a century. To prove ownership of the tunic, in accordance with the law, Fred provided an oral history of the piece—a story long passed on from generation to generation:

More than a hundred years ago, the tunic was a part of what was known as a Chilkat robe, a garment crafted out of mountain goat wool and cedar bark. Between its seams were woven various animal crests—important elements of a storied heritage. The robe itself bore tremendous ceremonial significance: The descendants of deceased tribe members wore the tunic during traditional Tlingit rituals honoring the dead.

The robe made its home in a wooden clan plank house called the Raven House. Two brothers, Kannalku and Kichnaalx, led the clan and served as the heads of the household. But one day the Raven House grew overcrowded and it was decided that Kichnaalx would leave to begin a new house. Because the robe could not be in two houses at once, it was split, with its two halves each made into a tunic, one for each house. For years afterward, the two tunics played vital roles in Tlingit funerary ceremonies.

Then, early in the 20th century, when an aggressive assimilation movement coerced indigenous people to shed and sell off reminders of their heritage, the tunics disappeared.

Museum records indicate that, in the 1920s or 19305, the Dartmouth tunic came into the possession of Axel Rasmussen, a school superintendent and a collector of Northwestern tribal objects. It was sold following Rasmussens death in 1945 and, after being passed across the country from collector to collector, the tunic was bought by a New York art dealer, who donated it to Dartmouth in 1959.

Just how much officials knew about the tunic when it first arrived in Hanover is a mystery, though Haak says that at the very least, they were aware that it had originated in Angoon. But those were the days long before repatriation became a buzzword among museum curators, and returning the tunic to its original owners likely didn't come up in conversation.

"The museum could have initiated a return, but that would have been very unusual," Haak says. "There is a different attitude now."

A new attitude doesn't always breed expediency. Though legal repatriation generally doesn't take longer than several months, the Kootznoowoo tribe found itself lacking the funds and the manpower to handle the paperwork necessary to formally reclaim the tunic. As a result, the process stalled.

In February 2002 Kootznoowoo tribal leaders asked the Central Council of the Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska, an organization representing several thousand Tlingit tribe members, to help in the repatriation effort. Thanks to the renewed support, the process was completed last October. Matthew Fred, the Tlingit elder who had originally identified the tunic, never lived to see it return to Angoon; he died in 1999. But Hood and Tlingit officials timed the tunics return to coincide with a memorial potlach—a traditional Native ceremony in which one or more guest tribes gather and receive gifts from the tribe hosting the event—being held in Fred's honor.

Haak arrived in Angoon last November, tunic in hand, and presented it to the tribe at the potlach. He recalls watching as Freds niece, in accordance with Tlingit custom, wore the tunic in tribute to her uncle. "It was terrific to see it immediately reintroduced into this cultural life," he says.

No one was more excited than the Tlingit themselves. Daniel Johnson, an Angoon native now living in Wrangell, Alaska, says the return of the Dartmouth tunic (the location of the second tunic remains unknown) and other cultural items from across the country is launching a resurgence of Tlingit pride. "Our little community is beginning to thrive again," he says.

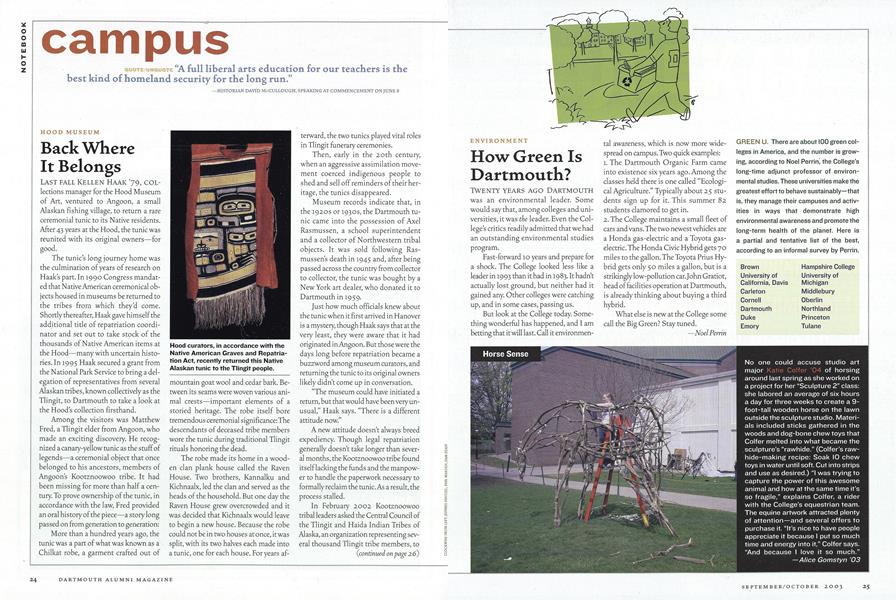

Hood curators, in accordance with theNative American Graves and RepatriationAct, recently returned this NativeAlaskan tunic to the Tlingit people.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Seduction of a Corporate Recruit

September | October 2003 By JONATHAN E. ZIMMERMAN ’98 -

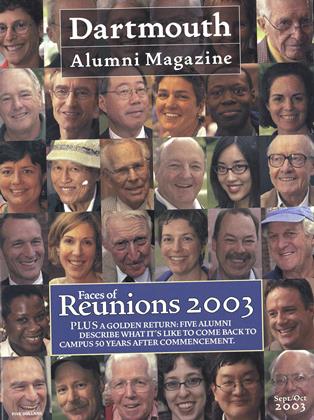

Cover Story

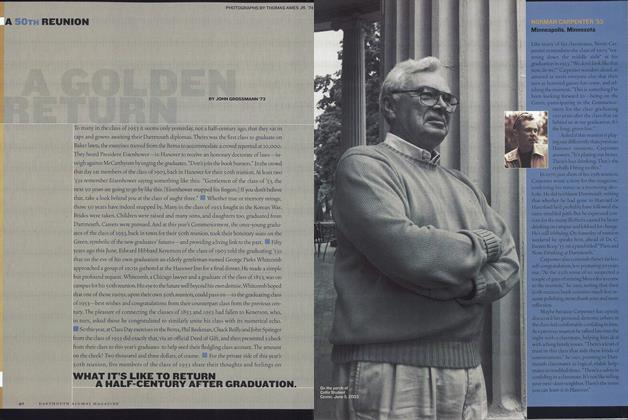

Cover StoryA Golden Return

September | October 2003 By JOHN GROSSMAN ’73 -

Feature

FeatureO Julie!

September | October 2003 By MEG SOMMERFELD ’90 -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

September | October 2003 By MIKE MAHONEY '92 -

Outside

OutsideGetting the Ax

September | October 2003 By Lisa Gosseling -

Student Opinion

Student OpinionLet the Hype Begin!

September | October 2003 By Kabir Sehgal ’05

Alice Gomstyn '03

-

Article

ArticleThe Write Stuff

July/Aug 2003 By Alice Gomstyn '03 -

Article

ArticleHorse Sense

Sept/Oct 2003 By Alice Gomstyn '03 -

Article

ArticleA Different Shade of Green

Nov/Dec 2003 By Alice Gomstyn '03 -

Interview

InterviewQ & A

Nov/Dec 2003 By Alice Gomstyn '03 -

Article

ArticleAddressing Success

Jan/Feb 2004 By Alice Gomstyn '03 -

Article

ArticleHire Education

May/June 2007 By Alice Gomstyn '03