Getting the Ax

The Ivy League’s first and only lumberjacks maintain a tradition that’s a cut below the rest.

Sept/Oct 2003 Lisa GosselingThe Ivy League’s first and only lumberjacks maintain a tradition that’s a cut below the rest.

Sept/Oct 2003 Lisa GosselingThe Ivy League's first and only lumberjacks maintain a tradition that's a cut below the rest. By Lisa Gosselin

On a subfreezing Saturday in January, Ben Honig '05 and Phil Marvin '03 are lying in a field outside Montreal, huffing on kindling they have shaved and stacked with Martha Stewart precision. "Four minutes!" shouts a nearby woman holding a stopwatch and clipboard. The students blow on the fire, desperately trying to bring a can of water to boil. As the flames lick dangerously close to the men's faces, a crowd of spectators chants, "Allez! Allez!"

The water isn't close to bubbling.

The previous contestants, two burly sophomores from Nova Scotia Agricultural College, had their can frothing over in a little more than four and a half minutes. They furiously chopped, stacked and lit their fire, then huddled so close to blow on it that their pants began to burn and they had to wriggle awkwardly in the snow to cool off. "That's the way I always do it," says Nova Scotia's Scott Reed, glancing down at his singed threads. "I go through several pairs of pants a season."

"Ten minutes; time is up!" announces the timekeeper with the clipped finality reserved for losers on The Weakest Link. The Dartmouth students roll away, coughing up cinders and patting down sparks on their green plaid team jackets, their water warm but hardly boiling.

The water boil-teams are given a can of water, a cedar log, an ax and three matches—was just one of the events that drew the Dartmouth team to compete last year at the 49 th annual Woodsmen's Day, held at McGill University's Macdonald campus, located on a sprawling lakefront estate just 25 miles from downtown Montreal. The lineup for the one-day event included snowshoe races and pole climbs. But most of the events involved slinging axes, wielding chainsaws with the precision of a dental pick or powering a giant, two-handled crosscut saw through a tree trunk.

Dartmouth students have a longstanding tradition of participating at the Macdonald event, and an equally longstanding tradition of getting their Carhartt-clad butts handed to them. This year was no exception. Ag students from Nova Scotia, each weighing 250 pounds, manhandled a massive log up a deck ramp in 16 seconds. Future foresters from SUNY's Environmental Science and Forestry School sent axes flying into a bull's-eye. The University of New Brunswick team arrived in a bus emblazoned with their sponsors name, saw manufacturer Stihl, and showed they knew how to use the products. Honig and Marvin watched in dismay as the other teams unloaded the buses. The heft of these two Dartmouth foresters combined wouldn't tip the scale much past 300 pounds.

The two other Dartmouth team members, John McCall-Taylor '03 and Anne Raymond '06, struggled with their first event, the pulp toss. The bocce of logging, the pulp toss involves throwing 4-foot, 20-pound logs a distance of 20 feet—and they must fall neatly within four stakes. McCall-Taylor breathed heavily into an inhaler. First-time lumberjill Raymond (recruited earlier that week) threw the log with all her pigtailed might, watching it fall short of the mark by several feet. "Hey, we're here just for fun," says Marvin, a computer science major from southern California. "Plus, it's kind of neat to tell people you are a lumberjack."

No one was surprised when McGill/Macdonald's varsity mens and women's teams swept the day. The Macdonald Woodsmen hold more victories than any other varsity sports team at McGill. Their coach John Watson, is the son of the man who started the event. Watson also manages the campus arboretum—which happens to be North America's largest. Team workouts are from 6 to 8 every morning. Practice starts off with 80 pushups. Snow or shine. Outdoors.

And no one was surprised that Dartmouth finished dead last. As the Dartmouth Web site states: "While many other schools that the Dartmouth woodsmen's team competes with have forestry as a varsity sport and hold tryouts, our club team is different...we'll take anyone at all, especially if they are silly."

Silly they may be, but Dartmouth students have one claim to fame that Canadians can't take away. As Marvin notes, "We thought of this first."

Dartmouth, in fact, introduced timbersports to intercollegiate competition. In 1947, a full seven years before the Canadians went at it, Dartmouth's legendary woodcraft advisor, Ross McKenney, organized a Woodsmen's Weekend. Like most lumberjacking competitions, Dartmouth's original event involved using a lot of sharp tools. But woven in were some Ivy League niceties that bespoke a liberal arts approach to being an outdoorsman:fly and bait casting, a two-man canoe race, a cooking contest and, in 1948, a competitive birdwatching event—in which teams were handed binoculars and asked to identify a kingfisher's nesting hole. (None of the contestants succeeded.)

A handful of other schools, including Williams and Kimball Union, showed up to compete at that first meet. Now the annual affair rotates among three colleges, with Dartmouth next scheduled to host in 2004.

Although the Dartmouth teams have occasionally won some events, James Taylor '74, a veteran of the woodsmen's wars, sums up the team's competitive history in one word: "miserable." Taylor, a hefty engineering major better known by the nickname "Pork Roll," got his start in timbersports the way most Dartmouth students do: He was thrown into a competition. Some Outing Club friends handed him an ax, gave him a week to practice and persuaded him to come to a meet at Paul Smith's College the following weekend. The outcome was predictable: Dartmouth lost. Less predictable was what happened to Taylor: He was hooked.

"This was a sport that was completely different—it didn't matter who won. There wasn't a tremendous amount of rivalry. We were all just out there chopping wood and having a good time," he recalls. All true, except Taylor decided it would be more fun if Dartmouth did better in the standings. So he set out to do something novel: practice, really practice. He began chopping regularly. He helped raise money for the team and they bought some good axes and blades (which can run to $300 each). He befriended a woodsman from the University of New Hampshire and they competed professionally on the county fair circuit one summer.

Next thing, Dartmouth was hosting the weekend again. And winning some of the events. And, like every real team, they had uniforms, which in this case were T-shirts declaring the men "Wood Peckers" and the women "Wood Pussies."

"Some of the best times of my life were those afternoons we'd be out chopping at Oak Hill," Taylor recalls. "I remember the smell of wood and the late afternoon spring sun and the good feeling you got after splitting a few logs."

Back in Montreal, the Dartmouth mouth lumberjacks are winding down. The chainsaws are, for now, quiet, and a bonfire roars. The raucous drinking that might have gone on in years past has been replaced with an athletic stoicism. John McCall-Taylor (no relation to Pork Roll) stands with an elbow propped on Raymonds shoulder. Her cheeks are flushed and she is talking a mile a minute. "I missed the first three times but I got the ax in the bark," she says. Marvin laughs and says, "Hey,you did great!" He goes on to tell the story of another first-time forester—the politically correct term, he notes, for "woodsmen"—they recruited several years earlier who came to Macdonald and won the ax-throwing event. "See, Anne, that could be you next year."

"And I'm going to stick around campus and help out," says McCall-Taylor.

"Yeah, and maybe we'll get Pork Roll back to coach some sessions," says Honig.

"We're hosting the Woodsmen's Weekend next year," says Marvin. "You know, we could win that."

Yes, Dartmouth could. But old traditions die hard.

Lisa Gosselin is a freelance writer and theformer editor of Audubon Magazine

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Seduction of a Corporate Recruit

September | October 2003 By JONATHAN E. ZIMMERMAN ’98 -

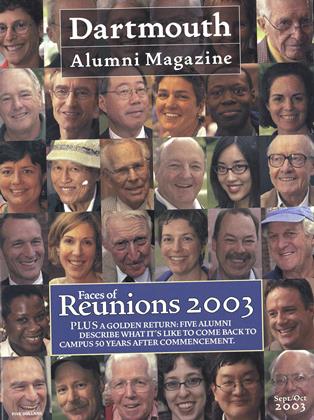

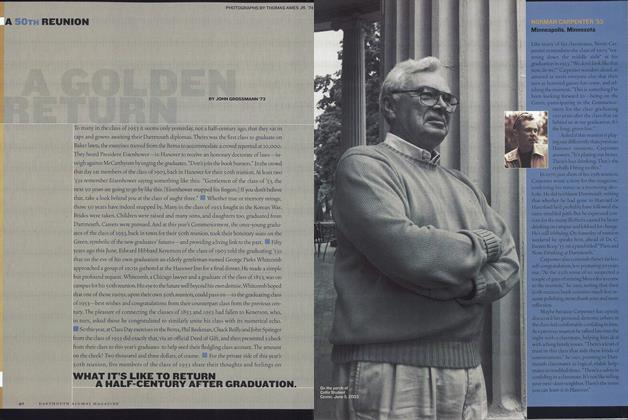

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Golden Return

September | October 2003 By JOHN GROSSMAN ’73 -

Feature

FeatureO Julie!

September | October 2003 By MEG SOMMERFELD ’90 -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

September | October 2003 By MIKE MAHONEY '92 -

Student Opinion

Student OpinionLet the Hype Begin!

September | October 2003 By Kabir Sehgal ’05 -

Article

ArticleBack Where It Belongs

September | October 2003 By Alice Gomstyn '03

Outside

-

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEStill Trippin’

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2014 By ED GRAY ’67 -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEThe Allure of Beauty

May/June 2003 By Henry Homeyer ’68 -

Outside

OutsideThe Literature of the Logbooks

Nov/Dec 2002 By Madeleine Eno -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEConfluences

MAY | JUNE 2014 By MICHAEL CALDWELL ’75 -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEFrugal Brugals

Nov/Dec 2003 By Nelson Bryant ’46 -

OUTSIDE

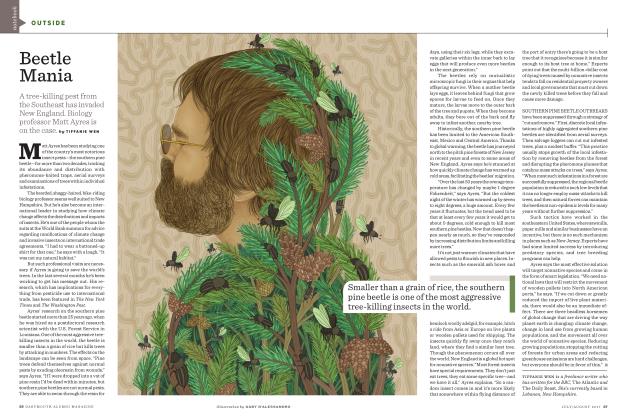

OUTSIDEBeetle Mania

JULY | AUGUST 2017 By TIFFANIE WEN