Animal Attraction

Where else but at Dartmouth would a librarian construct a ladder to help wayward chipmunks?

Mar/Apr 2004 Ted LevinWhere else but at Dartmouth would a librarian construct a ladder to help wayward chipmunks?

Mar/Apr 2004 Ted LevinWhere else but at Dartmouth would a librarian construct a ladder to help wayward chipmunks?

You ALREADY KNOW THAT DARTMOUTH College sits between the Connecticut River and the rolling hills of New Hampshire's western flank. It's an academic oasis, an urban island surrounded by the "green silence of wilderness," to borrow a line from Anne Morrow Lindbergh. You also already know that the campus is laced with greenbelts, some so spacious you could disappear for a while. But you may not know that wild quadrupeds and birds regularly appear on, over and in the College, attracted to the fruit, seeds, nuts, leaves, flowers, stems and flesh (theirs, not yours) found around campus, and to the pulse of the seasons and the lay of the land.

Sometimes they're also drawn to open windows. Buildings, and for no apparent reason, libraries in particular, are prime spots for sighting wildlife. About 20 years ago I caught a little brown bat in the stacks at Baker Library, not far from the mystery novels, and kept it alive for weeks on a diet of mealworms. And there's a crew of chipmunks, I'm told, that climb into the windows at Baker. Once inside, they need assistance getting back out. Chipmunks used to visit the old Map Room too, which prompted one cartographic librarian to build a rope ladder, which he hung out the window so the chipmunks could escape.

One spring about 15 years ago a male parula warbler, one of the most beautiful birds in eastern North America, landed on the sill of an open window at 102 Bradley Hall and began crooning during Tom Bickle's math class, punctuating the lecture with a rising, buzzy trill. Fortunately for the warbler, Bickle loves birds.

Many years ago the late Lawrence Kilham, a virologist at the Medical School, pulled into the horseshoe drive in front of Dana Library to find a barred owl in the midst of killing a gray squirrel, one of dozens of campus miscreants that depend on the largesse of philanthropic students to survive the winter.

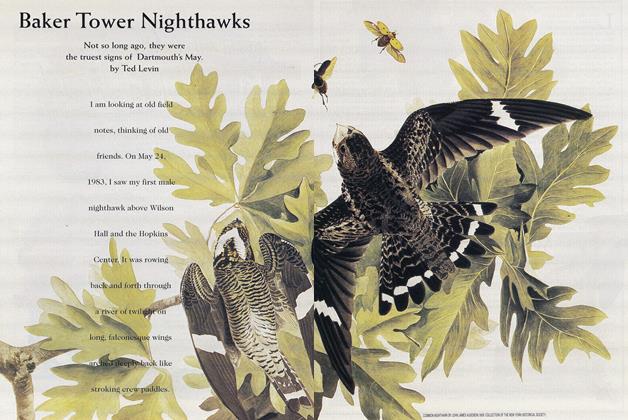

On warm February afternoons I've watched big brown bats trolling for bugs in front of the old Dartmouth gym, where I assume they spent the winter hibernating in the attic, lulled to sleep by dribbling basketballs. And up until the mid-1980s nighthawks courted above the Baker Clock Tower and nested on the gravel rooftops of nearby Kiewit and Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital. Sadly, they're gone now, part of a wave of change as open-field animals give way to those of the woodlands, which, of course, means different species appear on campus.

For a few days 10 years ago, a black bear destroyed birdfeeders on Occom Ridge, gorging on black oil sunflower seeds before moving off to points unknown. During the spring of 1995 a sow gave birth to twin cubs along Mink Brook, a heartbeat from downtown Hanover. When the cubs were fit enough to travel, the trio crossed Route 10, swam the Connecticut River and took up residence in Norwich for three weeks, grazing the green fields of the Montshire Museum. This past September another bear visited the campus. The animal got around—it was seen in front of Parkhurst, outside Berry Library's Novack Cafe, near the town athletic fields below Rip Road, near the apartments off North Park Street and in front of Baker Library, where more than 50 curious students surrounded it. The bear, somewhat disturbed by the attention, retreated up a nearby tree. By then the Hanover Police and Safety & Security officers were on the scene, directing the pedestrian traffic. Eventually the bear disappeared down a wooded ravine off Webster Avenue.

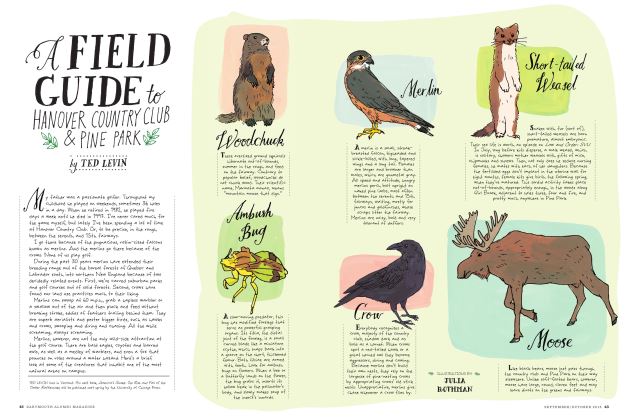

Deer are spotted regularly around campus and occasionally moose appear, much to the chagrin of police, who must contend with the traffic that inevitably results. Last spring a young moose created a minor jam on West Wheelock Street, where it stood watching the watchers halfway between the College and Ledyard Bridge. Several years ago a moose trotted across the Green in broad daylight.

Birding around the College can be both predictable and unpredictable. Every fall and spring migrating warblers pour through, pausing to feed and roost, en route to either the wintering grounds in the neotropics or the breeding grounds in the north. If weather patterns aren't favorable the birds may bivouac for days, enriching my strolls around the College. Last spring, for instance, a Cape May warbler, perhaps the most difficult warbler to spot in New England, spent three days luxuriating on campus. Also last spring a barred owl survived a crash into a window at Gilman Hall after being chased by a posse of crows, while across campus a pair of amorous pileated woodpeckers drummed on an elm outside President Wrights office in Parkhurst. In winter, birds from the far north sometimes settle across campus, feeding on crabapples, box elder seeds and elm buds. During the winter of 2002 flocks of bohemian waxwings and pine grosbeaks splashed red and yellow across the otherwise gaunt winter landscape.

Then there are random sightings: an adult bald eagle above Steele Hall, a peregrine falcon chasing pigeons over the Green, a kettle of broadwing hawks high above Bradley Hall. A couple of years ago a pair of merlins—small, swift, pugnacious falcons whose range is usually much farther north—nested in a pine on the golf course not far from the clubhouse. The merlins raised four young while entertaining a small army of birders. Every morning for several weeks the parents came screaming down the golf course to deliver food to their chicks, limp songbirds in their talons.

No animal sighting around campus, however, compares with the 1977 Animal Control Agents Report for the town of Hanover, given to me by a friend. Listed last below 961 animal complaints, including one gerbil bite and two runaway jackasses, was a note that read: "Investigated a report of an otter chasing a mailman." Animal control agent Stan Milo confirmed the report that he received a call from a mailman, who after being chased down the street by an otter, took refuge in someone's house. The post office offered no comment. The late E.B. White did, though. My friend sent the report to TheNew Yorker, and White responded: "Maybe that's what the postal service needs."

TED LEVIN, a naturalist, writer and photographer,is the author of Liquid Land: A Journey Through the Florida Everglades (University of Georgia Press). He lives in Thetford,Vermont.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

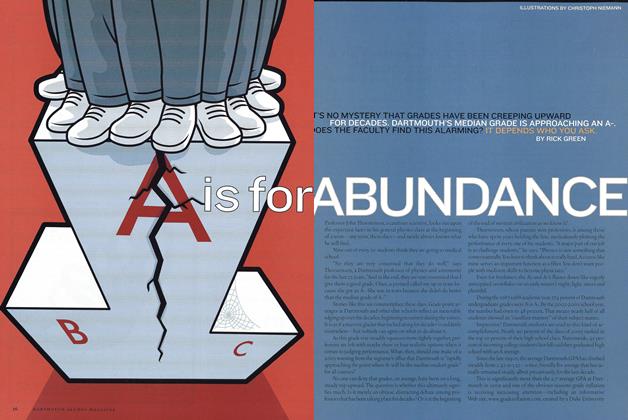

Cover StoryA is for Abundance

March | April 2004 By RICK GREEN -

Feature

FeatureA Day in the Life

March | April 2004 By JONI COLE, MALS ’95 -

Feature

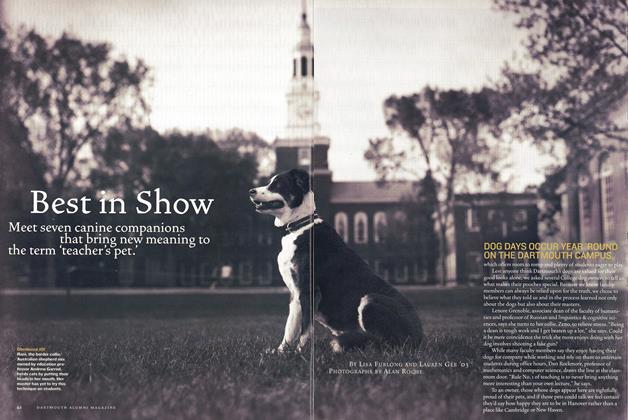

FeatureBest in Show

March | April 2004 By Lisa Furlong and Lauren Gee ’03 -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

March | April 2004 By MIKE MAHONEY '92 -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionSaturate, Don’t Isolate

March | April 2004 By David C. Kang -

From the Dean

From the DeanThe Fourth ‘R’

March | April 2004 By Michael S. Gazzaniga ’61

Ted Levin

OUTSIDE

-

OUTSIDE

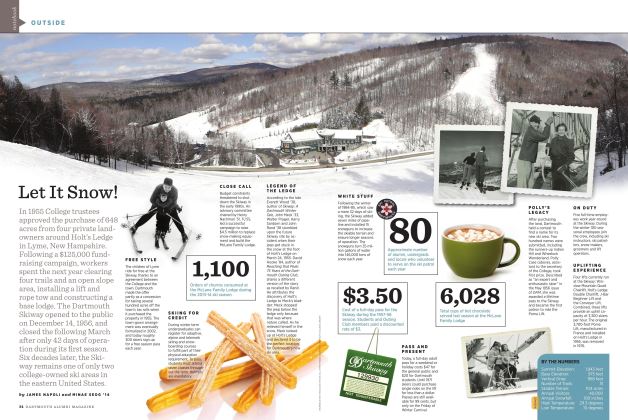

OUTSIDELet It Snow!

JAnuAry | FebruAry -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEThe Creek Kid

MAY | JUNE By BILL GIFFORD ’88 -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEThe Allure of Beauty

May/June 2003 By Henry Homeyer ’68 -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEDog Day Afternoons

Nov/Dec 2005 By LISA DENSMORE ’83 -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEConfluences

MAY | JUNE 2014 By MICHAEL CALDWELL ’75 -

OUTSIDE

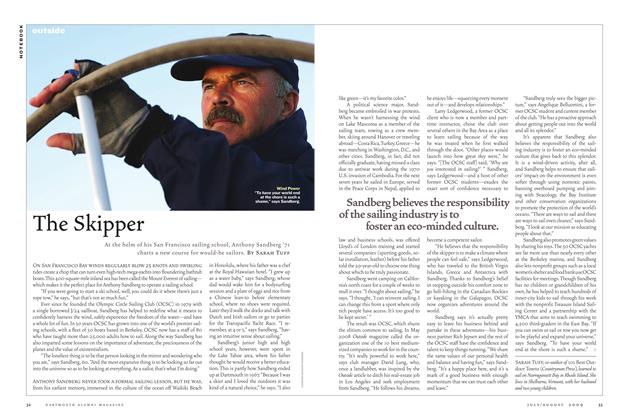

OUTSIDEThe Skipper

July/Aug 2009 By Sarah Tuff