Dog Day Afternoons

What you need to know about taking man’s best friend hiking on DOC trails and elsewhere.

Nov/Dec 2005 LISA DENSMORE ’83What you need to know about taking man’s best friend hiking on DOC trails and elsewhere.

Nov/Dec 2005 LISA DENSMORE ’83What you need to know about taking man's best friend hiking on DOC trails and elsewhere.

SOME DAYS I HAVE TO HIKE SIMPLY because of my dog, Bravo. We both get exercise. We both get to be outside, together. I enjoy the views. He enjoys the extra belly rubs and the odd scrap of sandwich. But hiking safely and responsibly with a dog involves more than simply walking through the woods with your favorite canine companion. The pitfalls can be as small as a tick or as big as a moose. And because dogs are often blamed for adverse environmental impact, it's important to minimize erosion.

Every time a person steps onto a trail with his pooch, both are ambassadors for everyone else who hikes with dogs. With increasing numbers of people and, therefore, dogs in back country areas, dog access has become a hot topic among many trail maintenance organizations, landowners and the various government agencies that oversee the trail systems.

While most dogs hike without problems, it only takes a few trailside incidents, a couple of outspoken dog-haters or several expensive dog rescues for wilderness areas to become more restricted to dogs—thus the following Ten Rules of Canine Trail Etiquette:

1. Limit the total number of dogs in your hiking group to two, regardless of the number of humans. Three or more dogs hiking together become a pack of dogs, which can intimidate other hikers. Three or more dogs are less likely to mind their manners with that much peer pressure, and the trample effect increases because paws and feet tend to land in the same spots.

2. Put your dog on a leash whenever you meet others—people or dogs—on the trail. You never know if other hikers are fond of dogs or dog-phobic. A dog may be friendly in general, but an odd body odor, the sound of hiking poles clattering on the rocks or a huge frame pack (which makes the approaching hiker look like a giant) can put a dog on the defensive. Even if your Rover is a total beta dog, you have better control over unexpected behavior if he's on a leash.

3. Dogless hikers have the right of way. The accepted rule of the trail is that uphill hikers have the right of way, but if you meet a dogless human, he has the right of way no matter which way he is heading. Besides putting your dog on a leash, you should step to the uphill side of the trail with your dog held close to you.

4. No jumping up, sniffing, licking, growling or barking. None of these should be an issue, assuming a basic level of obedience training and socialization, with the exception of sniffing. Dogs sniff as a way to identify other things and because they are natural hunters and scavengers. It is a rare dog that will not "ask" for a taste of someone else's lunch, but if you satisfy your dog with its own snacks and water, it will be less likely to beg from others. 5. Shout a cordial hello to tell your dog that it is a friend—not a foe—approaching. People usually greet each other on the trail, but it is a prerequisite when you hike with dogs, which are naturally protective of their masters. As soon as you see another person, say hello and exude friendliness. This will put your pet at ease.

6. Clean up after your dog. Dogs are not wild animals. Their refuse is not part of nature. No one appreciates dog poop on the trail. As with human waste, either bag it or bury it. When burying it, do so at least 200 feet from the trail and water sources, and at least 6 inches deep.

7. Keep your dog on the trail. The party line says keep your dog with you and under control at all times, but let's be reasonable. Pick the moments it may romp with unbridled glee when it won't bother other people, dogs or wildlife and where it will have limited impact on the environment. The exception is on summits above 4,000 feet, among them Mt. Moosilauke, where vegetation is extremely rare and fragile. In the alpine zone, it is imperative that you prevent your dog from roaming.

8. Leave plants and wild animals alone. Common plants are necessary for controlling trail erosion. If your dog nibbles a few dandelions, it will not hurt anything, but if it digs up the dandelions, it will. Likewise, do not allowyour pet to terrorize the native fauna. A dog rarely catches anything, but the chase forces a wild animal to expend extra energy, which might weaken it among its natural predators, particularly during the winter, when food sources are scarce.

9. Be careful of untreated water. People are warned never to drink water in the backcountry no matter how pure it looks, due to the risk of ingesting the giardia lamblia parasite or another nasty organism. Dogs are susceptible to waterborne illnesses too, so technically, you should discourage your dog from drinking water along the trail. Yeah, right. Only the most prudish dogs will ignore a babbling brook, and most will jump into a swampy pool of stagnant algae if they are hot and thirsty enough. While the party line says no, the voice of reason says guide your dogs to clear, running water as much as you can. Always carry enough water for both you and your dog, as water sources often dry up. In the rare case that your pet contracts diarrhea or shows other symptoms, take it to a veterinarian as soon as possible.

10. Be prepared for wildlife encounters. Most wildlife is nocturnal and extremely shy, but dogs have a keen sense of smell and an instinctive ability to track other animals. Though rare, wildlife encounters do happen. If a wild animal approaches, particularly during daylight hours and if its fur is mangy and it drools or has foam around its mouth, put your dog on a leash immediately, grab a long, sturdy stick (to ensure the animal stays a distance from you and your dog) and depart the area. If you or your dog is bitten through the skin, seek medical attention as soon as possible. If you or your dog touches the animal, you must wash the area thoroughly with soap and water. The rule of thumb is to scrub for 20 minutes!

When dogs pick up bear scent or the scent of any large animal, most will pause and begin to growl nervously, although a few breeds (hounds in particular) will want to chase it. Put your dog on a leash right away If you see a bear, you should remain calm and keep a firm grip on your dog's leash at heeling length. Do not run, as this might trigger a prey-chase reaction. Talk calmly in a low voice, which tells the bear you are human. Hold your free arm out to the side, or open your jacket and hold it out to make yourself seem larger. If the bear charges anyway or even bluffs a charge (which is often a precursor to the real thing), let your dog go. Fight back by kicking or punching. If it perceives you as difficult prey, it might depart in search of an easier meal.

A moose is the largest animal that you will most likely see in the woods, particularly in swampy areas. Like all wild animals they will usually wander away if humans are near, although sometimes they will just stand and stare, and, in rare instances, they will charge if protecting young or during the rutting season (early fall). If a moose blocks the trail, keep your dog on its leash, then shout loudly to shoo the beast away. If the moose does not move or if it seems aggressive, take a detour yourself. And if it charges, your best chance is to put a large tree between you and the animal.

LISA DENSMORE'S second book, Best Hikes with Dogs: New Hampshire & Vermont (Mountaineers Books) was published inSeptember. She lives in Hanover.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureForged by Flame

November | December 2005 By LEE MICHAELIDES -

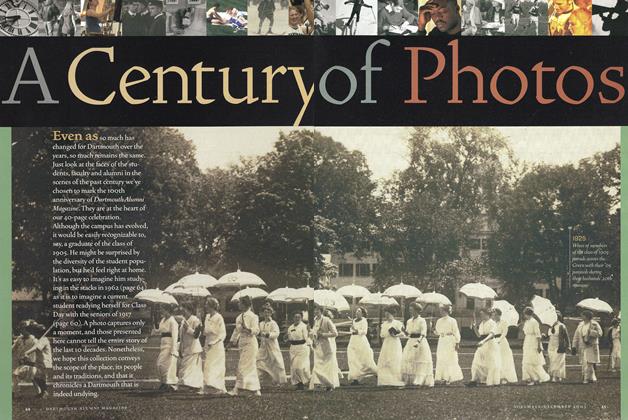

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Century of Photos

November | December 2005 -

Feature

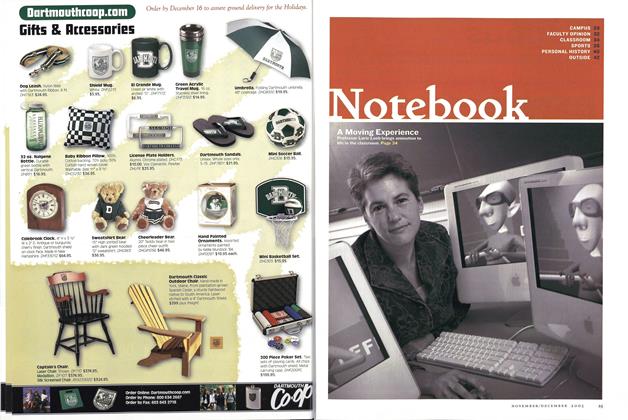

FeatureNotebook

November | December 2005 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

November | December 2005 By Heather Brubaker '97, Heather Brubaker '97 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYPaying the Price

November | December 2005 By JEFF DUDYCHA ’93 -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONEggheads vs. Meatheads?

November | December 2005 By DAVID KANG AND ALLAN STAM

LISA DENSMORE ’83

OUTSIDE

-

OUTSIDE

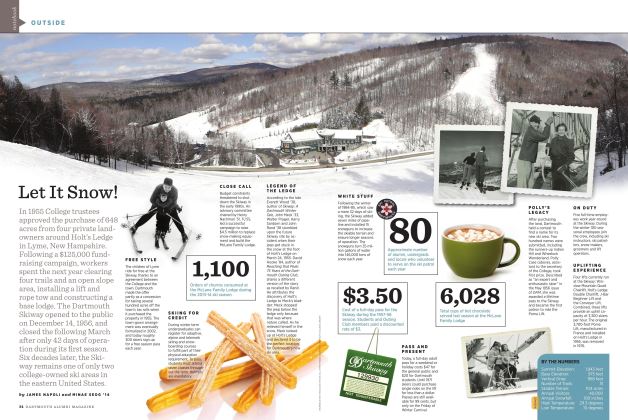

OUTSIDELet It Snow!

JAnuAry | FebruAry -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEHarvard Leads the Way

Jan/Feb 2005 By Bryant Urstadt '91 -

Outside

OutsideRunning With Wild Abandon

July/Aug 2002 By Jay Heinrichs -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEConfluences

MAY | JUNE 2014 By MICHAEL CALDWELL ’75 -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDECall Me Kook

May/June 2011 By Peter heller ’82 -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEThe Skipper

July/Aug 2009 By Sarah Tuff