A Vicious Cycle

A Dartmouth student comes to terms with life-threatening urges.

Nov/Dec 2008 Latria Graham ’08A Dartmouth student comes to terms with life-threatening urges.

Nov/Dec 2008 Latria Graham ’08A Dartmouth student comes to terms with life-threatening urges.

MY FIRST REAL MEMORY OF DOING something wrong is from when I was 7:1 ate some Girl Scout cookies I wasn't supposed to. After I was done I stuck the boxes under the edge of my mattress, certain no one would think to look there. Later my parents would search my room for something and find empty, flattened cookie boxes. Instead of learning that sneaking food was bad, I got smarter about hiding the evidence.

My closet eating started early, but it took a while to develop into an eating disorder. I started skipping meals. I tried not to think about food by occupying myself with other matters, but eventually I would break down and eat. I'm not talking about running to the corner store for a bag of potato chips. I'm talking about buying a tub of Oreo ice cream and devouring it on my way to pick up my brother from a friends house.

One day I finished the ice cream and felt horrible. Then I remembered something my P.E. coach taught me in elementary school when I said I was sick and didn't feel like running: I could continue to sit there, sick and miserable, or I could throw up, feel better and join the other kids. I asked him how I would go about it, and he showed me by pretending to stick his index and middle fingers down his throat. It looked painful, and I decided that I wasn't that sick.

A couple of years later I was that sick, so I decided to try it. Eventually purging became a system of checks and balances. I started losing weight, though not enough to satisfy me. I wanted to be thin, chic and sophisticated—like my mother.

In middle school I moved from Tennessee to Spartanburg, South Carolina, and was desperate to buy the same kind of designer jeans worn by a girl I admired. My mother told me I could get them if they fit. They didn't. She said if I lost "a little bit more," they would fit better. I forgot about the jeans but I focused on the words "a little bit more." It became my mantra.

By high school I was as awkward as ever but I had a group of band geek friends who were just as awkward. Music was my favorite hobby and I also got involved in all the organizations that didn't have conflicting schedules. I made more friends, which meant I had to keep track of which food lie I told to whom. I sometimes managed to avoid eating at school, but at home I ate anything and everything I could get my hands on. Sometimes I ate lots and lots of bread even though I hate bread. Other times it was just whatever happened to be there—jars of peanut butter, a vat of pasta sauce.

My parents never abandoned me or anything like that—they were in the picture, but I isolated myself. I would get up, go to school, attend one of my many meetings, go to dinner with my band friends, have band practice and then go home for potential dinner No. 2. When I wasn't at rehearsal I was in youth advisory board meetings or doing community service. I kept myself busy and my; parents accepted that.

Nonetheless the pressure was getting to me. The cycle of hinging and purging was now ingrained. I had rituals around it. I kept plastic bags in my room because I was too scared of getting caught throwing up in the bathroom. It no longer gave me the original feeling of relief and release: I needed something more.

I don't know where I got the idea of self-injuring. My mom thinks I got it from white kids at school—but she thinks I got everything bad from white kids at school: my eating disorder, my interest in veganism, my attraction to white boys. Wherever I got it from, I used it as a way of relieving stress—and as punishment for one of any possible reasons I might be mad at myself. At the ripe old age of 14 I would go to my underwear drawer, pull out the razors (I remember the brand—Helping Hand) and punish myself for my sins. At first it gave me a feeling of freedom. Over time it became a self-made prison. I stopped wearing short-sleeved shirts because people would ask too many questions.

People were starting to worry. During my sophomore year I read my academic team coach some of my more morose poems; later in the day I was summoned to the guidance counselors office.

Maybe my coach had seen the scars. I'd graduated from small slits from a serrated kitchen knife to long fluid lines that crept toward my wrists. This wasn't the first time I'd contemplated death. In the past I'd wanted to do it in my sleep after downing "medical cocktails," vile concoctions of pills from my parents' medicine cabinet mixed in cough syrup.

Before my parents could comprehend the trouble I was in I left home for boarding school. This was an idea I pursued against their wishes. I auditioned behind their backs—and gained admission—to the South Carolina Governors School for the Arts in Greenville. I convinced them to let me go. I got what I wanted—or got what I thought I wanted. It was change: I was leaving the people who knew me and going somewhere to excel at...something. It didn't matter what. It was a chance for change.

Once I got to school the work went well, at least in the beginning. I was used to not having to work too hard, to performing after just a few minutes of practicing. This school was different. I realized I wasn't as good at the clarinet as I had been led to believe.

During this time my bulimia was at its most volatile. Some of my classes ran through lunch and dinner periods, and my parents didn't want me to skip meals, so they took me grocery shopping every week. This meant a lot of food in my room. The school cafeteria was buf- fet style, which was dangerous. If I had the time I would eat, throw up, finish eating, sneak off to the science wing and throw up again. On Fridays my friends and I would get together and mass order Chinese food for dinner. Sometimes in my room by myself I'd order meals from Steak-Out then throw up in a trash bag.

One day my roommate saw my arms and told the school nurse. I was sum- moned from European history to Nurse Gail's office. She asked to see my arms. I resisted. She asked until I finally yielded. Her ensuing horror was warranted: My entire left arm was a series of strawberry gashes—some fresh from earlier that day. She called my dean, who called my parents, and they had a serious chat. My mother had known for more than a year that I was doing something to my arms but I think it was too much for her to process. I went home for the weekend and my mom told me I had to see someone to talk about my problems—or I had to leave school.

I chose the former. I ended up with a therapist who looked like Donna Karan but dressed like a lumberjack. I hated her. She was trying to take me off my path to greatness. If I stopped cutting, I knew I would fall apart. If I could make it through the year then I might be able to entertain the thought of stopping, but not before then. So I learned to fake it and play the therapists game. She tried to tease out my words, but I shut her down.

One of my suitemates must have squealed about my food issues, because somewhere along the line Donna Karan accused me of having an eating disorder. My parents and I vehemently denied it. I was fine. I mean, I was a little plump but that could be fixed with some exercise. The reality was that I had my head in the toilet three to four times a day. I couldn't play my clarinet half the time because my fingers were swollen from edema, but I was absolutely fucking fine!

My senior spring a school friend noticed that I was taking a lot of laxatives. She approached me about it, and I told her the truth. She was the first person I could talk to about my semiadult fears: I didn't know where I was going to go to college (I applied to 40 of them) and I thought my habits were so out of hand that they were going to eventually kill me. She helped me talk about my issues, but our paths would soon split: It was time for college.

My parents wanted me to go to col- lege in the South, but I said it was time for a change. I decided to branch out. I applied to Dartmouth and after being accepted came to visit the campus. I had a wonderful host, and even though there were spots of snow on the ground in April, I thought I was in love. I submitted my contract for admission before I left the campus. I chose not to think about how competitive it would be. When I arrived in the fall I realized I was with the same type of intense students I knew from high school. I wanted to impress people, so I pushed myself. I knew I was a great cook, so I started hosting dinner parties in McCulloch, my dorm. I bent over backwards to please people who didn't give a damn about me. In addition to the parties I read other peoples papers, volunteered with the Dartmouth Alliance for Children of Color and worked at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center. Later I served as an undergraduate advisor for freshmen, maintained a social life as i a sister at Tabard and tried to go to class—the latter with mixed results. I wasn't happy. I began to wonder if Id chosen the wrong school. I'd changed everything and still there was no magic: I wasn't the beautiful, articulate college girl I'd dreamed of being.

had from high school, which had keloided over, leaving thick raised tracks on my arms. I wasn't ready to shatter the illusion that I was perfect and completely together.

As it turned out one of my professors would do that for me. My freshman summer I decided to take a Shakespeare course for my English major. After a couple of botched papers and many missed classes the professor told me I had to talk to him or someone in student health services about whatever was bothering me. I chose health services because I could lie there—even as I realized lying had gotten me nowhere.

The therapist from student services was much better than Donna Karan. I started being honest about what was going on—and had been going on for years. But even a good therapist couldn't stop the downward spiral I was in. I was cutting myself several times a day and bingeing and purging even more. I started thinking about suicide again. I told a friend about my idea of setting myself on fire and he told my dean, who sent me home on medical leave midway through sophomore year.

During the next nine months I went to two treatment centers. The second one was only for people with eating disorders, so I had something in common with the other patients. But there I focused on another level of difference. I was a double minority: the only plus-sized patient and the only person of color.

Although I liked and got along with the other patients sometimes it was painful to listen to them. People who were going blind from malnutrition talked in groups about feeling fat. Even harder was the separation I felt because of my skin color. When I was younger I didn't think about race, but that changed after I came to Dartmouth. It's a very race-conscious place. There's a general sense that the white students look down on the minorities as affirmative action admits, and minority students tend to self-segregate intensely to deal with the oppression and stereotypes. As a freshman, when I was the only black person in my English seminar I thought nothing of it; as a junior, when I realized I was the only black person in my medieval literature class, I almost had a panic attack. That's how much Dartmouth had changed me.

Fortunately I had a great therapist at the treatment center who was a minority and a plus-sized woman. We talked about my family and the pressure I put on myself to be like my mother. We talked about the pressures that Dartmouth's white, male-dominated atmosphere put on me and the limited roles I could play: I could be the motherly black woman who cares for everyone or I could raise my voice and be defined as a bitch. When I imagined myself in the future—as a corporate lawyer, which at the time was my goal—I pictured someone who used her reasoning to manipulate people in a smooth, ladylike way. As I talked to my therapist I began to realize that this isn't the future I want.

I wish I could write about some miracle for the ending of this story, but there isn't one. No one rode in on a white horse and saved me. I didn't have a life-changing epiphany. God didn't perform a miracle and cure me so that I never thought about food again. He did make it possible for me to get the help that I needed, and now, two years out of treatment, I've begun to believe. When something goes wrong that I don't understand I realize I can get through it. I still have bad days but maintain hope. I have a supportive group of Dartmouth friends, a supportive Gospel Choir family, and I'm starting to accept who I am. I don't expect to be perfect but I do think I can be happy. I'm allowing myself to enjoy things along the way. Recently I auditioned for a play. In short sleeves.

At the ripe old age of 14I would pull out the razors and punish myself for my sins.

Many people had put me in a ' racialized," gendered box. The box became oppressive.

LATRIA GRAHAM is living in New YorkCity, completing her degree. This is adaptedfrom Going Hungry: Writers on Desire, Self-Denial, and Overcoming Anorexia, edited by Kate Taylor and published in September,with permission of Anchor Books, a divisionof Random House.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

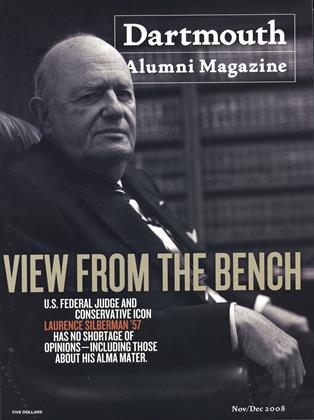

COVER STORY

COVER STORYView From the Bench

November | December 2008 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

FeatureOn the Money

November | December 2008 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

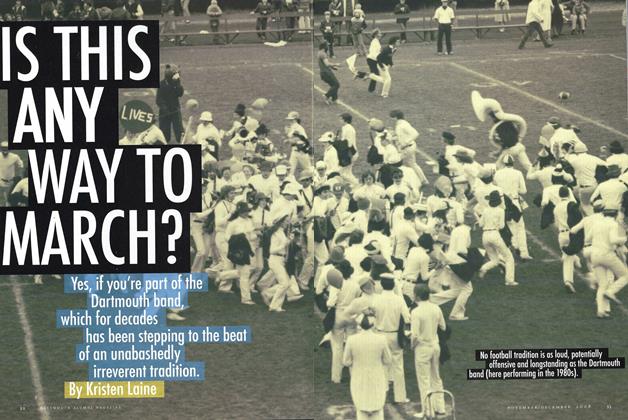

Feature

FeatureIs This Any Way To March?

November | December 2008 By Kristen Laine -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

November | December 2008 By TIM FITZGERALD -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

November | December 2008 By Bruce Beasley '61 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTELuck of the Draw

November | December 2008 By Bryant Urstadt ’91

PERSONAL HISTORY

-

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYLosing The Lottery

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2015 By DAVID M. WOOD ’77 -

Personal History

Personal HistoryMeryl, Overrated?

MAY | JUNE 2017 By DENIS O'NEILL ’70 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYPaying the Price

Nov/Dec 2005 By JEFF DUDYCHA ’93 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYThe Quantum World

Mar/Apr 2009 By Louisa Gilder ’00 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYOne of the Boys

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2014 By LYNN LOBBAN -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYMeasure of the Mind

Mar/Apr 2002 By Robbing Barstow ’41