SEVERAL WELL-PUBLICIZED STUDIES this past winter have highlighted what Dr. Michael Sateia, professor of psychiatry and director of Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Centers 33-year-old Sleep Disorders Center (SDC), already knew: Alot of people don't get enough sleep—and not because they can't find enough time.

'At least 40 million Americans suffer from some sort of sleep disorder," says Sateia, president of the prestigious American Insomnia Association, who's made a career of studying and treating them. "In our DHMC clinic we've got six beds and they're in use five or six nights a week. In three other facilities [in Keene and Berlin, New Hampshire, and Berlin, Vermont] we've got six more beds and they're just as busy." A newly referred patient can expect to wait two to three weeks to get into one of them, be wired to a bank of instruments and spend a technician-monitored night in a quiet room appointed more like a pleasant hotel suite than a hospital room.

Seventy percent of the overnight patients treated at SDC are suffering from obstructive sleep apnea—recurring breathing pauses brought about by a blockage of airflow to the lungs, caused by a musclerelaxed collapse of soft tissues in the back of the throat. When the oxygen deprivation gets strong enough, the sufferer wakes briefly, starts breathing normally again and falls back asleep. When it happens 20 to 30 times a night, a patient needs aggressive treatment and is usually referred to a pulmonary specialist.

In the center's outpatient clinic, insomnia is by far the No. 1 complaint. Once external factors such as a drug interaction or disruption by a sleep partner are ruled out, diagnosis falls within the centers primary expertise: a psychiatric evaluation to find out why a patient can't sleep. It can be difficult. "We have some patients who come in so sleepy that they can't stay awake long enough for us to take a history from them," says Sateia. And it can be frightening: "We've had school bus drivers, airline pilots and nuclear power plant operators," he says.

Besides its clinical role, the center also carries a research function. Because SDC's physicians and technicians have tradi- tionally come from psychiatry—as op- posed to the pulmonary specialists who dominate sleep centers at other institu- tions—its primary research focus has been on insomnia. Wil Pigeon, a post- doctorate fellow in behavioral medicine, is currently applying cognitive behavioral therapy, which addresses thinking that affects behavior, to some cases.

Education is also a priority, and be- cause SDC has been around so long (when the center opened in 1971 it was one of two in the country, now there are more than 470), graduates of the Dart- mouth Medical School (DMS) are well grounded in the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia. Courses are required in all four years, while at many other medical schools there is no requirement at all. To Sateia, who teaches at DMS and is making progress toward getting sleep medicine formally recognized nationally as a medical sub-specialty, all the recent media attention has been a good thing.

But do the stories mean sleep disorders are on the rise? "We don't know," says Sateia. "There's no hard data. What is measurably on the rise, however, is peoples awareness of them. We're working to take that even higher." —Ed Gray '67, Tu '71

Logging Z's The Sleep Disorders Centerat DHMC is one of the country's oldest.

QOUTE/UNQUOTE Discoveries that impact health and disease are often made at the edge of fields, where differences between fields become blurred. It is here that novel insights are made." DMS PROFESSOR ETHAN DMITROVSKY, DELIVERING THE 17TH ANNUAL PRESIDENTIAL LECTURE ON HIS GROUND-BREAKING TREATMENT OF LUNG CANCER, FEBRUARY 11

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Great Disconnect

May | June 2004 By ED GRAY ’67, TU’71 -

Feature

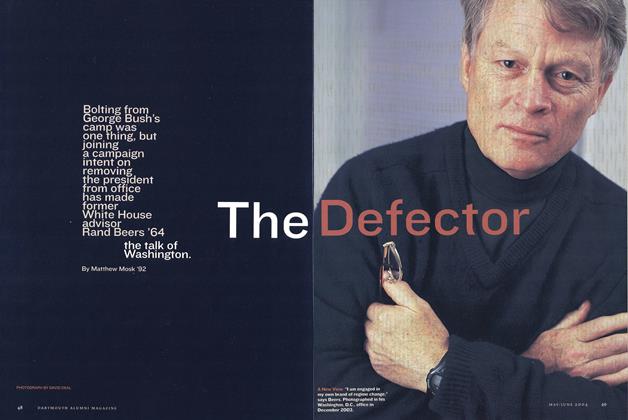

FeatureThe Defector

May | June 2004 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

FeatureYou Can’t Always Give What You Want

May | June 2004 By ALICE GOMSTYN ’03 -

Feature

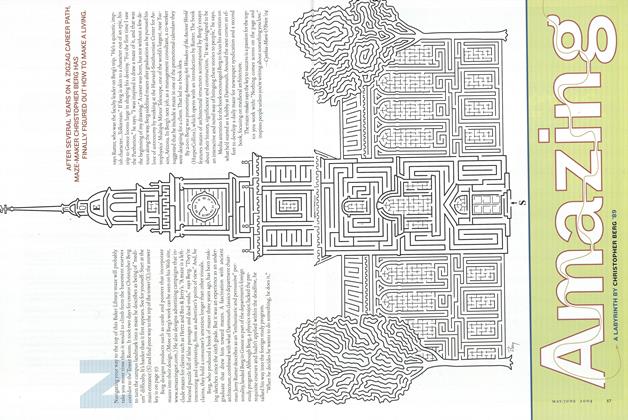

FeatureAmazing

May | June 2004 By Cynthia-Marie O'Brien '04, CHRISTOPHER BERG '89 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

May | June 2004 By MIKE MAHONEY '92 -

Sports

SportsStraight Shooter

May | June 2004 By Ed Gray ’67, Tu’71