Double Trouble

Whether he’s skiing the slopes or riding the dusty trail, two-sport phenom Carl Swenson ’92 stays at the top of his game.

Sept/Oct 2004 Chris Milliman, Adv’96Whether he’s skiing the slopes or riding the dusty trail, two-sport phenom Carl Swenson ’92 stays at the top of his game.

Sept/Oct 2004 Chris Milliman, Adv’96Whether he's skiing the slopes or riding the dusty trail, two-sport phenom Carl Swenson '92 stays at the top of his game.

AS THE PREEMINENT TWO-SPORT endurance athlete in the world, Carl Swenson may be the greatest American athlete you've never heard of. While Swenson spends the winter crisscrossing North America and northern Europe as the captain of the U.S. Nordic ski squad, he passes his summers competing as one of Americas top professional mountain bike racers. When one season ends, with the cheers from race spectators still echoing in his ears, Swenson drops everything from one sport and picks up the tools of the other.

Swenson has accomplished enough in each sport that either one would qualify as a successful career on its own. On his skis, he's raced in two Olympics (1994 and 2002), won 10 national championships and finished fifth in the 50-kilo-meter race at the 2003 Nordic World Championships, the best result by an American in 20 years. On his bicycle, Swenson has won two national championships (2000 and 2001), medaled at numerous national events and raced as part of the U.S. team at the world championships since 1998. Outside magazine recently place Swenson No. 8 on its list of "Ultimate Bad Boys of the Outdoors," calling him an "endurance freak" and the "fittest athlete in the country."

Answering the obvious questionhow can he do it?—Swenson is nearly nonchalant. "Doing two sports, in distinct seasons and environments, keeps it exciting and fresh," says the former twotime captain of Dartmouth's Nordic team. "I haven't gotten tired of it so far; it's been fun for me."

A top-level skier even in the junior ranks, Swenson didn't take up bike racing until 1994, when he entered his first mountain bike race at the urging of his older brother. Two years later he signed a professional contract with the BMW-ProFlexTeam. In college Swenson had demonstrated a knack for turning the pedals: He commuted home several times for school breaks by biking 100 miles to his home in North Conway, New Hampshire, requiring him to maneuver the ups and downs of the mountainous Kancamagus Highway. "It's a great ride," says Swenson, who majored in political philosophy.

Dartmouth Nordic head coach Ruff Patterson coached Swenson for four years and has remained close with his former team captain, seeing him several times a year at mountain bike and ski races. For Patterson, Swenson's singular ability to enjoy competition and not get frustrated by failure separates him from other top athletes.

"That guy absolutely loves racing," says Patterson. "For sure he loves the training component. I have never seen anybody so unafraid to compete and race. He's one of the few guys who can be get- ting hammered in a race series, and when you talk to him its like nothings going on. He can't wait until the next day. He's been that way as long as I've known him. He's different from most people: He's totally unafraid of what a poor outcome might be."

Skier Peter Vordenberg has viewed Swenson from just about every angle. The two raced against each other in high school and college, and were teammates at the 1994 Olympics. Now one of the U.S. teams coaches, Vordenberg marvels at Swenson's seemingly imperturbable optimism.

"One of the greatest things about having him on the team is that the younger athletes can see him finish 50th one day, and the very next day he finish- es in the top 15," says Vordenberg. "The young skiers see that and it helps them battle through hard times."

Swenson's ability to float seamlessly between the ski and bike worlds may hinge on the distinct hemispheres in which the two sports operate. He has carved out rep- utations in each sport that don't rely on his accomplishments in the other. This, says Vordenberg, keeps Swenson from getting tired of either. But it may also prevent him from getting enough credit for both.

Swenson races his bike nearly every weekend from April through August, then takes a few weeks off to train before starting the international ski season in November, racing nearly every weekend until the season ends in March.

While his teammates in either sport pour all their energies into preseason preparations, Swenson grits his teeth and absorbs the jarring transition from one sport to the other. Unlike most athletes, who spend the majority of their year preparing for competition, Swenson uses competition as his training. With so little time between the bike and ski seasons, extended blocks of training are a luxury he cannot afford.

"Going into bike racing is so hard because I go right into racing, whereas with skiing I have four weeks of dry-land and a month of ski training before I have to do a race," he says. "I can't keep up with anybody on roller skis when I first start. It's a tough transition for the first few weeks. I really enjoy being able to focus 100 percent on cycling in the summer and then same thing in the winter for skiing."

Swenson's hectic schedule leaves him with no fixed spot to call home. For 10 months a year training camps and race sites around the world fill the bill. Such an unrelenting schedule has its advantages—principally, seeing the world and making a living doing what he lovesbut has left no time to start a family. A salary from his mountain bike contract, endorsement money from ski sponsors and the support of the U.S. Olympic Committee keep the bank account full enough for the time being. With nothing like mortgage or car payments to make, Swenson has chosen a life stripped of fixed financial obligations.

"I get a days-on-the-road deduction," he says, laughing. "I travel a good twothirds to three-quarters of the year. All my friends from college are lawyers and doctors and they're all having kids right now. I keep getting baby pictures. It's funny to see that."

Looking down the road, Swenson sees the 2006 Winter Olympics in Turin, Italy, as a possible endpoint for his career as an elite athlete. At 33 Swenson is old enough to know all the tricks but not old enough to feel the ravages of age. For now, his preparations for the 2004-05 ski sea- son and his hopes for a much-coveted spot on the World Cup medal stand involve riding a bike for a living. He'll prepare for winter's frostbite cold by baking on his bike through summer's dusty heat.

"All this sports stuff is nutty," says Vordenberg. "He's just one special nut among other nuts."

He Glides, He Rides “I don't feel like Ihave to decide which sport is myfavorite,” says the endurance racer.

CHRIS MILLIMAN is a writer and photographer living in Lyme, New Hampshire. He isa correspondent for VeloNews.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

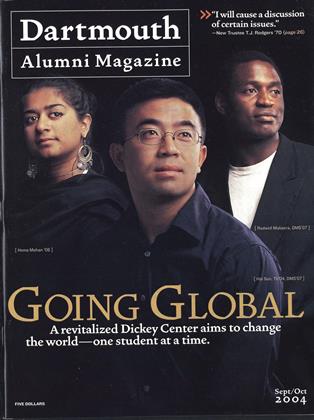

Cover StoryThe Global Classroom

September | October 2004 By CHRISTOPHER S. WREN ’57 -

Feature

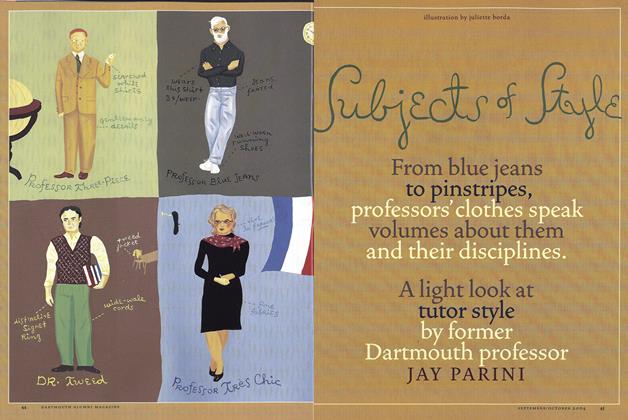

FeatureSubjects of Style

September | October 2004 By JAY PARINI -

Feature

FeaturePiano Man

September | October 2004 By BONNIE BARBER -

Personal History

Personal HistoryDeath on the Chilko

September | October 2004 By John W. Collins ’52 -

Interview

Interview“A Change Agent”

September | October 2004 By Lisa Furlong -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

September | October 2004 By MIKE MAHONEY '92