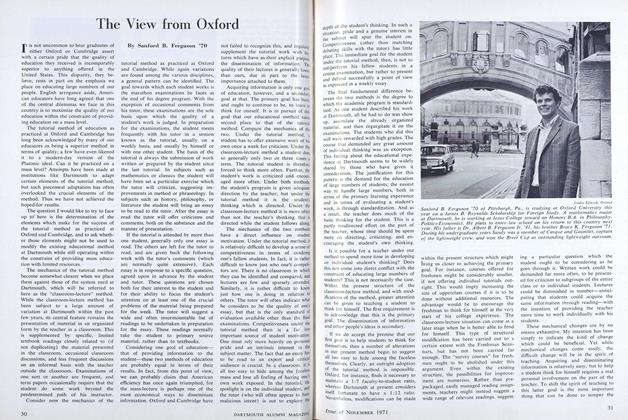

The Global Classroom

A revitalized Dickey Center for International Understanding aims to change the world—one student at a time.

Sept/Oct 2004 CHRISTOPHER S. WREN ’57A revitalized Dickey Center for International Understanding aims to change the world—one student at a time.

Sept/Oct 2004 CHRISTOPHER S. WREN ’57A REVITALIZED DICKEY CENTER FOR INTERNATIONAL UNDERSTANDING AIMS TO CHANGE THE WORLD—ONE STUDENT AT A TIME.

Basking in the sun-dappled splendor of early autumn, the Dartmouth campus feels blissfully remote from the woes of the world. Yet the Iraq war and other conflicts, globalization tensions, climactic change, the AIDS .scourge and other seemingly intractible problems are not overlooked on the second floor of the southeast wing of Baker Library, the current home of the John Sloan Dickey Center for International Understanding.

The Dickey Center was established to honor Dartmouth's 12th president, who in 1946 told students—among them returning war veterans—that "the worlds troubles are your troubles." Through his tenure from 1945 to 1970, Dickey maintained that "there is nothing wrong with the world that better human beings cannot fix."

Since 1982 the Dickey Center (initially the Dickey Endowment) has applied President Dickeys vision of an international Dartmouth education by linking academic scholarship to foreign realities. The center sponsors a minor in war and peace studies as well as student programs such as the World Affairs Council and the Dartmouth Coalition on Global Health. The center, with a staff of five employees, also provides financial assistance through the Dickey International Internships, awarded to about-29 students a year, which cover airline tickets and bare-bones living expenses abroad. It also has devised other research opportunities for students and some faculty members.

A College report in 1999 endorsed a pivotal role for the Dickey Center in enhancing the international dimensions of a Dartmouth education. Although it long ago outgrew its undeserved reputation as an ATM machine for students looking to travel, some people are still hard pressed to say what the center does. That should change after die center moves to higher-profile quarters in the Haldeman Academic Centers building, a new complex to be built next year on Main Street north of Baker Library.

The greatest impetus for internationalism may be the dazzling technological innovations, from the Internet to jet-age travel, that have shrunk the dimensions of the world. Nearly two-thirds of Dartmouth students now spend some time studying abroad.

"Theivorld is growing smaller and together, but also breaking into piece's in a very dangerous way," says the Dickey Centers director, Kenneth Yalowitz, a former American ambassador to Belarus and Georgia. Yalowitz came to the centerin July 2003 after 35 years as a career diplomat, mostly in the forme? Soviet Union. He has wit- nessed the centripetal forces drawing people together across national barriers through, for example, communications. Yet other centrifugal forces, manifested in ethnic and religious conflicts, keep people apart, he says, as does the economic chasm segregating haves from have-nots. "Dickey has a critical role in making these international realities, and low to deal With them, an integral part of a Dartmouth education," Yalowitz says. "No student should leave here without a basic understanding of such pressing issues."

Yalowitz has resurrected "Great Issues," a course Introduced by President Dickey, in the form of public lectures. Yalowitz also helped create a faculty committee to advise the center and is promoting faculty groups on democracy building, global health and other interdisciplinary concerns. He envisions a visiting fellows program that would invite prominent specialists from around the world to the center as scholars-in-residence. The expanding range of programs will stretch thin a budget, funded mostly by alumni, amounting to a little more than $1 million a year.

The Dickey Center insists that applicants come up with their own projects and work out the logistics themselves. Here's a look at five students and their projects, all conducted during the pastyear:

HEMA MOHAN '06

For Mohan, studying standard Arabic at Dartmouth left her curious to hear how the classical language of the Middle East metamorphosed into the colloquial dialect spoken in the United Arab Emirates, a federation of seven sheikdoms along the Persian Gulf.

A practicing Hindu, Mohan wanted to see how non-Muslim women get treated under Islamic law; ethnic Indians make up half of the population of the Emirates. Her own parents immigrated from southern India to Morristown, New Jersey.

Mohan represents the kind of longterm investment that the Dickey Center has made in nearly 500 Dartmouth students during the last 18 years. "It gives them a chance to really explore, to take a new direction," explains Margot de l'Etoile, who administers the internships.

Students do not earn academic credit for the internships. Still, Mohan elected to spend a winter term at the American University of Sharjah, an emirate subject to Islamic law. She worked for Munsin al-Musawi, an Iraqi-born specialist in Arabic exile literature. NonMuslims like herself, she found, were exempted from the strict standards of dress demanded of Muslim women, though occasionally she did don the hejab, or traditional head covering.

Mohan was impressed by the diversity among the Gulf Arabs and the warmth of their hospitality. "I did leave here with the image of the archtypical Arab," she says. "I came back realizing that it was a very varied culture."

Since returning from Sharjah, Mohan has decided to major in Arabic with a minor in Islamic cultural anthropology and earn a Ph.D. Then she wants to join the State Department as an Arabic-speaking diplomat.

"Now I don't find the ignorant comments people make about Arabs funny," she says. "They're just people."

HAI SUN, TH'04, DMS'07

Sun has traveled a winding road from the impoverished Chinese province of Guizhou to the Thayer School of Engineering, where he just earned his doctorate. Sun studied computer science in Anhui province before winning a scholarship to St. Johns College in Annapolis, Maryland, where he started over, studying philosophy and history. Then he applied to Thayer to master biomedical engineering. "I had a different background, but Thayer is very interested in that," Sun says.

During his six years in Hanover, Sun also made rime to complete his first year at Dartmouth Medical School. With some funding from the Dickey Center, Sun went off to western Zambia for five weeks with the Dartmouth International Health Group, where he worked in a rural health clinic near the Zambezi River. He tested children for pediatric bladder stones and detected the prevalence of schistosomiasis, a snail-borne parasite that, if left untreated, can destroy the kidney. The clinic lacked even a centrifuge to separate the tell-tale sediment of parasites in hundreds of urine samples he collected.

When he returned to Hanover, Sun searched the Web for a second-hand centrifuge compact enough to be flown back to the clinic in Zambia. It cost $2OO, so, Sun says, "We did a bake sale at Thayer School. All my friends contributed."

Sun intends to apply his engineering skills from Thayer to image-guided neurosurgery after he graduates from Dartmouth Medical School. "Neurosurgery requires a lot of accuracy," he explains. "The current mechanism assumes the brain is a rigid structure, like steel, but apparently that is not true. Brain tissue begins to deform during surgery." By taking images during surgery to compensate for such changes, Sun hopes to pioneer a more accurate navigation of the brain when surgeons operate.

RODWELL MABAERA, DMS'07

When Mabaera, 25, left his native Zimbabwe five years ago, it was a country ravaged by AIDS. After studying chemistry and mathematics at Colby College, he enrolled at Dartmouth Medical School, despite his difficulties with snowy winters and classes in English. He had spoken Shona at home in Chinhoye.

After his first year at medical school, Mabaera returned to Zimbabwe for two months, with support from the Dickey Center and the Dartmouth International Health Group, to study the distribution of rural health care. He began at a teaching hospital in Harare, where, he said, "I spent two weeks delivering babies because they didn't have anyone else to do it."

Traveling 50 miles northeast to Makumbe, he surveyed residents about their awareness of AIDS and the HIV virus that causes it. AIDS victims were grateful to talk to someone who cared. "It made a difference that somebody was interested in their lives," he says. "I'd talk about the AIDS problem every chance I got."

Twenty-five percent of Zimbabweans are infected with the virus that causes AIDS, according to Mabaera. Some clinics report HIV rates as high as 40 percent, he says, though these fell to 10 or 20 percent in conservative rural areas. For the young people he counseled, AIDS was a daily reality. "These people wake up and say, 'My father is going to die,' or 'l'm going to get married; what am I going to do?' " he says.

Back at Dartmouth Mabaera presented his field research on Zimbabwean attitudes toward AIDS. "Just being at home for those two months," he says, "I felt I made a difference in the medical community."

Once he earns his Dartmouth medical degree, Mabaera hopes to practice family medicine, or possibly surgery, in Zimbabwe. "Then maybe I'll make a difference at a higher level," he says.

ALEX GELMAN '06

Gelman turned to the Dickey Center last winter to help fund an internship at the International Bar Association in London, where he researched human rights abuses. This last summer he sought help with a more ambitious project.

Gelman, who is from Oceanside, New York, led a team of Dartmouth students to restore a neglected Jewish cemetery in Kaminka, a town in Belarus. Before the Nazis occupied Kaminka in World War 11, 90 percent of the towns 3,000 residents were Jews. Now, Gelman said, 1,500 people, none of them Jewish, live there.

The students found the cemetery clogged with weeds and trampled by cows. Some headstones had been stolen. The students cleaned up the graves and built a fence to mark "holy ground." The Russian Gelman learned at home from his Ukrainian immigrant parents let him interpret for other Dartmouth students.

This was the third time that Dartmouth students have worked on cemeteries in Belarus, with funding from the College, the Dickey Center and the Jewish student organization Hillel. Not all students were Jews.' 'We wanted to make sure there was diversity," says Gelman,who is Jewish. "Jews and non-Jews pickup on different things. The Jewish kids know the history of the Holocaust." The work trip included what he called "spiritual" visits to the old Jewish ghetto in Warsaw and the Nazi death camp at Auschwitz.

"Every single Dartmouth student said it changed their life," Gelman says. "A lifechanging experience for 15 people—we had to be doing something right."

It was Gelmans second such trip to Belarus, to the distress of his parents, who remember the persecution of Jews in Ukraine. "My mother was very much against me going," he admits. But Gelman, who is majoring in philosophy and economics, had no regrets about taking time to restore dignity to the Jewish graves.

"If we didn't do it, who would?" he asks. "It had to get done."

ANNE BELLOWS '06

Bellows was lured to Dartmouth by its smorgasbord of foreign language courses. Her brother John Bellows 'O4, learned Chinese. "I thought, if he can do it, maybe I can learn several languages," she says. "I'm now studying French, and I want to audit Russian or Arabic."

Growing up in Fort Collins, Colorado, Bellows also studied Spanish for six years. An interest in sustainable agriculture took her as a Dickey intern to live three months in the dirt-poor Achuapa Valley of rural Nicaragua. Idealistic intentions did not carry her very far.

"Whenever you're trying to do good, there's an implication that you're superior," she says. "But when I went down there, that was not the case. I gave up a lot of ideas and said, 'How can I fit in?' "

Bellows' culture shock included wading daily to work through a river where families were washing their clothes, children and pigs. When the electricity failed, she cooked and ate by candlelight. Village leaders hesitated to show her around or confide their needs. "There's a certain shame imposed by poverty, even if it's poverty beyond your control," she says.

As she struggled to win over the farmers, she says, "they accepted me as a student who was learning from them. My presence became less about helping and more about relating to them as a person."

Bellows built a Web site to help the farmers market their crop of sesame seeds, pressed into sesame oil. Sometimes she joined them in the fields, swinging a hoe. They wouldn't entrust her with a machete, she complains, "because I was a girl."

Bellows returned to Dartmouth prepared to do much more. "I am still passionate about alleviating suffering created by an unjust world," she says, "and at some point I'd like to accomplish something."

CHRISTOPHER S. WREN worked for more than 28 years for The New York Times as a reporter, foreign correspondent and editor. He now lives inFairlee, Vermont, and senes on the board of visitorsfor the Dickey Center.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureSubjects of Style

September | October 2004 By JAY PARINI -

Feature

FeaturePiano Man

September | October 2004 By BONNIE BARBER -

Personal History

Personal HistoryDeath on the Chilko

September | October 2004 By John W. Collins ’52 -

Interview

Interview“A Change Agent”

September | October 2004 By Lisa Furlong -

Sports

SportsDouble Trouble

September | October 2004 By Chris Milliman, Adv’96 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

September | October 2004 By MIKE MAHONEY '92