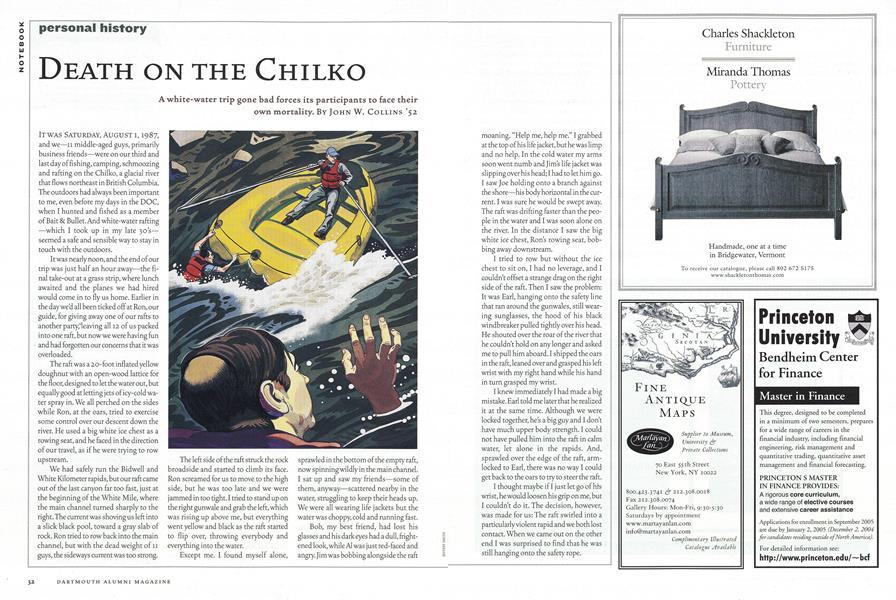

Death on the Chilko

A white-water trip gone bad forces its participants to face their own mortality.

Sept/Oct 2004 John W. Collins ’52A white-water trip gone bad forces its participants to face their own mortality.

Sept/Oct 2004 John W. Collins ’52A white-water trip gone bad forces its participants to face their own mortality.

IT WAS SATURDAY, AUGUST I, 1987, and we—11 middle-aged guys, primarily business friends—were on our third and last day of fishing, camping, schmoozing and rafting on the Chilko, a glacial river that flows northeast in British Columbia. The outdoors had always been important to me, even before my days in the DOC, when I hunted and fished as a member of Bait & Bullet. And white-water rafting —which I took up in my late 30sseemed a safe and sensible way to stay in touch with the outdoors.

It was nearly noon, and the end of our trip was just half an hour away—the fi- nal take-out at a grass strip, where lunch awaited and the planes we had hired would come in to fly us home. Earlier in the day weU all been ticked off at Ron, our guide, for giving away one of our rafts to another party,''leaving all 12 of us packed into one raft, but now we were having fun and had forgotten our concerns that it was overloaded.

The raft was a 20-foot inflated yellow doughnut with an open-wood lattice for the floor, designed to let the water out, but equally good at letting jets of icy-cold water spray in. We all perched on the sides while Ron, at the oars, tried to exercise some control over our descent down the river. He used a big white ice chest as a rowing seat, and he faced in the direction of our travel, as if he were trying to row upstream.

We had safely run the Bidwell and White Kilometer rapids, but our raft came out of the last canyon far too fast, just at the beginning of the White Mile, where the main channel turned sharply to the right. The current was shoving us left into a slick black pool, toward a gray slab of rock. Ron tried to row back into the main channel, but with the dead weight of 11 guys, the sideways current was too strong.

The left side of the raft struck the rock broadside and started to climb its face. Ron screamed for us to move to the high side, but he was too late and we were jammed in too tight. I tried to stand up on the right gunwale and grab the left, which was rising up above me, but everything went yellow and black as the raft started to flip over, throwing everybody and everything into the water.

Except me. I found myself alone, sprawled in the bottom of the empty raft, now spinning wildly in the main channel. I sat up and saw my friends—some of them, anyway—scattered nearby in the water, struggling to keep their heads up. We were all wearing life jackets but the water was choppy, cold and running fast.

Bob, my best friend, had lost his glasses and his dark eyes had a dull, frightened look, while Al was just red-faced and angry. Jim was bobbing alongside the raft moaning, "Help me, help me." I grabbed at the top of his life jacket, but he was limp and no help. In the cold water my arms soon went numb and Jims life jacket was slipping over his head; I had to let him go. I saw Joe holding onto a branch against the shore—his body horizontal in the current. I was sure he would be swept away. The raft was drifting faster than the people in the water and I was soon alone on the river. In the distance I saw the big white ice chest, Ron's rowing seat, bobbing away downstream.

I tried to row but without the ice chest to sit on, I had no leverage, and I couldn't offset a strange drag on the right side of the raft. Then I saw the problem: It was Earl, hanging onto the safety line that ran around the gunwales, still wearing sunglasses, the hood of his black windbreaker pulled tightly over his head. He shouted over the roar of the river that he couldn't hold on any longer and asked me to pull him aboard. I shipped the oars in the raft, leaned over and grasped his left wrist with my right hand while his hand in turn grasped my wrist.

I knew immediately I had made a big mistake. Earl told me later that he realized it at the same time. Although we were locked together, he's a big guy and I don't have much upper body strength. I could not have pulled him into the raft in calm water, let alone in the rapids. And, sprawled over the edge of the raft, armlocked to Earl, there was no way I could get back to the oars to try to steer the raft.

I thought maybe if I just let go of his wrist, he would loosen his grip on me, but I couldn't do it. The decision, however, was made for us: The raft swirled into a particularly violent rapid and we both lost contact. When we came out on the other end I was surprised to find that? he was still hanging onto the safety rope.

I tried again to row but we barreled down into another rapid and I lost an oar overboard. We spun out of control in the current, banging into rocks, crashing over falls into churning white canyons, more rocks, more rapids. Earl was taking a terrible beating. The river was so steep I could see we were going downhill, moving faster and faster. I remember a sour, metallic taste in my mouth; the constant roar of the rapids; repeatedly being thrown into the bottom of the raft; the sky and the sun swirling around the steep, gray canyon walls; green then white water curling over the raft and washing out through the floor boards.

Then we drifted into relatively calm water, and, miraculously, I found the missing oar floating alongside the raft. In my mind it was now every man for himself. I kept thinking that if I could just get rid of Earl I would be okay: It wasn't fair for him to be hanging onto my raft and I wished he would just let go so I could save myself.

Up ahead I saw something red and blue caught in an eddy, moving slower than we were. As we drew closer I saw it was Dick, floating very peacefully in his life jacket, face down in the water. I still remember saying to myself, "There will be deaths." Earl was on the other side of the raft and I didn't tell him about Dick.

I don't know how long we were on the water. People later told us we went more than a mile through the rapids, but I have no memory of time or distance—just of more rapids and more rocks and more noise. I was dead tired and my arms ached, and I could no longer pull on the oars. Then, surprisingly, the current again eased and we were sucked up close to shore. I shouted to Earl to grab a passing tree branch. He let go of the raft, grabbed the branch and was gently swung by the current into the bank.

Right away I had control of the raft and with one stroke pushed up to the shore, where I tied up to a tree just a few yards below Earl. He was hypothermic and shivering uncontrollably. I took off my life jacket and shirt, cut loose his jacket and wet shirt, and held my bare chest against his until he started to feel warm and I started to shiver. It was very warm on shore, and after a while we felt better, although both of us were exhausted and he was badly bruised.

We sat on the bank for half an hour trying to figure out what to do. I told him about Dick's body, and we agreed that everyone else was dead and that no one else would be coming down the river that day. We debated what to do. I wanted us to get back in the raft but Earl said there was no way he could go back on the water. He wanted to climb up out of the canyon, but I was more afraid of heights than of the river.

We did agreed that we shouldn't separate, and I finally said I'd try it his way. We started to climb the canyon wall, digging our feet in the loose, gray rocks and pulling ourselves up on scrawny branches. A couple of times we nearly lost our footing, and wed watch a small avalanche of loose shale clatter and tumble back down the slope and splash into the river. I was far more frightened than I had been on the river. We later found out that the fiercest rapids lay just beyond where we put in, and had we gone back on the water, we probably would have perished.

We finally got to the top of the canyon, and followed game trails along the high bluff, a quarter mile above the water. At one point we looked down at the river and saw a group of brightly colored kayaks clustered on the far shore, well out of earshot. The kayakers were gathered around the big white ice chest and what looked like a body. We speculated about who it might be, and then continued along the ridge. After about four hours a Royal Canadian Mounted Police helicopter that was searching for survivors found us and took us to the landing strip where we were to have had lunch at the end of our vacation.

We later found out that our guide, Ron—younger and more athletic—had abandoned us by jumping onto the rock without even getting his feet wet. To his credit, he did organize the rescue effort. Five in our party were found dead: my old and closest friend, Bob, the guy who had lost his glasses; Jim, whom I failed to pull into the raft; Dick, whose body I saw floating; and Gene and Stu, neither of whom I remember seeing in the water. Six of us survived, includingjoe, the guy I saw cling- ing to a branch, sure he would be swept away. Mike and Arthur were only in the water a few seconds; both remembered seeing me in the raft heading downstream. Al drifted the greatest distance—he must have gone past me at some point—and was banged up worse than Earl, but had finally got himself to shore and was rescued just about the time Earl and I were picked up by the helicopter.

I know that each of us still wonders why we were chosen to live. And now, some 17 years later, though I no longer have bad dreams about it, I am still haunted—especially in late July—by that sunny first day of August on the Chilko.

JOHN W. COLLINS retired as president andCOO of Clorox in 1989. He lives in Cloverdale,California, and wrote this story for a correspondence course taught by Tom Hyman '58.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Global Classroom

September | October 2004 By CHRISTOPHER S. WREN ’57 -

Feature

FeatureSubjects of Style

September | October 2004 By JAY PARINI -

Feature

FeaturePiano Man

September | October 2004 By BONNIE BARBER -

Interview

Interview“A Change Agent”

September | October 2004 By Lisa Furlong -

Sports

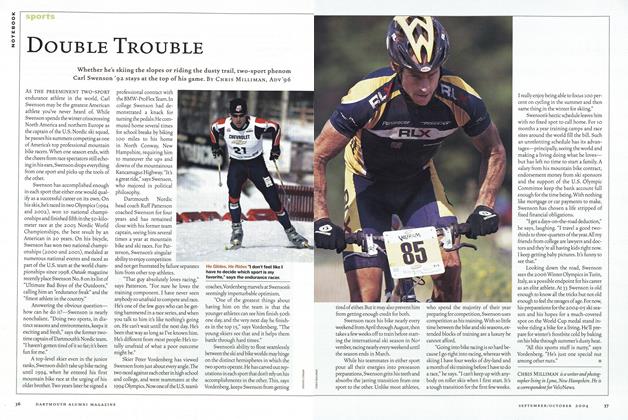

SportsDouble Trouble

September | October 2004 By Chris Milliman, Adv’96 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

September | October 2004 By MIKE MAHONEY '92

Personal History

-

Personal History

Personal HistoryMeryl, Overrated?

MAY | JUNE 2017 By DENIS O'NEILL ’70 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYPaying the Price

Nov/Dec 2005 By JEFF DUDYCHA ’93 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYGolden Girl

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2013 By JUDITH GREENBERG ’88 -

Personal History

Personal HistoryBody Of Knowledge

Nov/Dec 2003 By Kirsten Andrews ’97 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYMeet the Beatles!

JULY | AUGUST 2019 By RICHARD HERSHENSON ’67 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYMeasure of the Mind

Mar/Apr 2002 By Robbing Barstow ’41