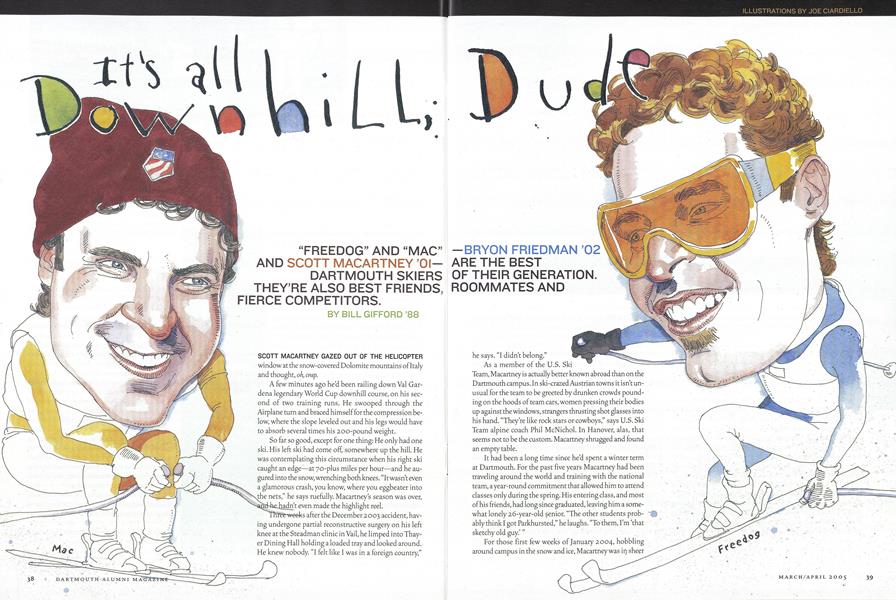

It’s All Downhill, Dude

“Freedog” and “Mac”—Bryon Friedman ’02 and Scott Macartney ’01—are the best Dartmouth skiers of their generation. They’re also best friends, roommates and fierce competitors.

Mar/Apr 2005 BILL GIFFORD ’88“Freedog” and “Mac”—Bryon Friedman ’02 and Scott Macartney ’01—are the best Dartmouth skiers of their generation. They’re also best friends, roommates and fierce competitors.

Mar/Apr 2005 BILL GIFFORD ’88"FREEDOG" AND "MAC" -BRYON FRIEDMAN '02 AND SCOTT MACARTNEY '01 SKIERS ARE THE BEST THEY'RE ALSO BEST FRIENDS,OF THEIR GENERATION. FIERCE COMPETITORS. ROOMMATES AND

SCOTT MACARTNEY GAZED OUT OF THE HELICOPTER window at the snow-covered Dolomite mountains of Italy and thought, oh, crap.

A few minutes ago he'd been railing down Val Gardena legendary World Cup downhill course, on his second of two training runs. He swooped through the Airplane turn and braced himself for the compression below, where the slope leveled out and his legs would have to absorb several times his 200-pound weight.

So far so good, except for one thing: He only had one ski. His left ski had come off;somewhere up the hill. He was contemplating this circumstance when his right ski caught an edge—at 70-plus miles per hour—and he augured into the snow, wrenching both knees. "It wasn't even a glamorous crash, you know, where you eggbeater into the nets," he says ruefully. Macartneys season was over, and he hadn't even made the highlight reel.

Three weeks after the December 2003 accident, having undergone partial reconstructive surgery on his left knee at the Steadman clinic in Vail, he limped into Thayer Dining Hall holding a loaded tray and looked around. He knew nobody. "I felt like I was in a foreign country," he says."I didn't belong."

As a member of the U.S.Ski Team,Macartney is actually better known abroad than on the Dartmouth campus. In ski-crazed Austrian towns it isn't unusual for the team to be greeted by drunken crowds pounding on the hoods of team cars, women pressing their bodies up against the windows, strangers thrusting shot glasses into his hand. "They're like rock stars or cowboys," says U.S. Ski Team alpine coach Phil McNichol. In Hanover, alas, that seems not to be the custom. Macartney shrugged and found an empty table.

It had been a long time since he'd spent a winter term at Dartmouth. For the past five years Macartney had been traveling around the world and training with the national team, a year-round commitment that allowed him to attend classes only during the spring. His entering class, and most of his friends, had long since graduated, leaving him a some- what lonely 26-year-old senior. "The other students probably think I got Parkhursted," he laughs. "To them, I'm 'that sketchy old guy.'"

For those first few weeks of January 2004, hobbling around campus in the snow and ice, Macartney was in sheer misery. His left knee was a swollen, aching mess, and the right one, which the doctors had left alone, wasn't much better. Taking two economics classes at once, to complete his major, didn't help.

He lived for Saturday afternoons, when he'd comandeer a Woodward dorm TV and watch his teammates on the Outdoor Life Network, shouting and ranting and probably scaring the other residents. He didn't care: These were his buddies. For one day a week, he got to be with them, albeit as a TV viewer, in St. Anton or Kitzbuhel or Chamonix or wherever the World Cup ski parly happened to be that weekend.

He cheered the loudest for Bryon Friedman '02, his best friend and roommate both on the road and at Dartmouth. On the ski circuit they were inseparable, known by their nicknames "Mac" and "Freedog"—and now the 23-year-old Friedman, at least, was having the best season of his career. Macartneys pleasure was bittersweet. "It was frustrating," he says, "because I'd see my teammates not skiing well, on courses I liked, and I'd go, 'I definitely should have been there!' "

JUST TWO WEEKS BEFORE MACARTNEY'S DECEMBER 2003 crash, both he and Friedman had been on the verge of breakout seasons after years of fighting their way through the ranks of international competition. Macartney had raced in a few World Cups already and had even skied in the 2002 Olympics in Salt Lake City, finishing 25th in the Super Giant slalom (Super G). But he'd been discombobulated by injuries since then, and he hadn't had any good results in a while. Friedman, an up-and-comer, was entering his rookie season on the World Cup circuit.

They'd spent previous years skiing the lower-profile Europa Cup, a series of events held at smaller venues across Europe. "It's the bush leagues," Macartney says. Sometimes they'd show up to find six inches of snow on the hill, the race canceled, and nobody would have bothered to tell the Americans. But Friedman placed well in some Europa Cups, while Macartney won a North American Cup title (for Super G) in 2003. They were ready for more. By early that December they were poised for the second World Cup downhill of the season, at Beaver Creek, near Vail. It was a packed weekend of skiing, including two World Cup downhills and a Super G. The only problem: Just one of them would be able to start the downhills. Because of complex World Cup selection rules, Friedman and Macartney were competing against each other for the last U.S. starting spot.

"That was unfortunate," Friedman says now. "You can't help but think, I wanna race. But the way I look at it, if Scott's skiing faster, he should get that spot." They tried not to be awkward around each other, but the situation underscored the reality of life at the top level of sport, where friendship matters a lot less than results. "It's a dogfight at the races, and it can be a dogfight within the team, as well," says one U.S. coach.

As it happened, one of their teammates crashed and injured himself in training, so both Friedman and Macartney got to climb to the start house at the top of Beaver Creeks double-black-diamond Birds of Prey course, one of the steepest on the World Cup circuit. Their speed coach, John McBride, was looking for both to finish in the top 30 of these races, which meant they would score World Cup points—and, more importantly, earn confidence and better start positions in future races.

Friedman started first, since he'd had a faster qualifying run. On that sunny Friday in December he swooped down the course to take 23rd place and pumped his fist for joy—for a World Cup rookie, 23 rd is like a victory. A few minutes later, Macartney broke the timing beam in 32nd, scant hundredths of a second out of the points. Two days later Macartney redeemed himself with a 26 th place in the Super G and rewarded himself with a little fist-pump of his own. But the guy everyone was talking about was Friedman, World Cup rookie.

In the following weeks Friedman announced his arrival on the World Cup scene. At Val Gardena, where Macartney crashed, Friedman clocked the second-fastest training run, shocking competitors and coaches alike. In early January, at Chamonix, he finished an amazing 10th place in the downhill—beating several European favorites. By the end of the season he was a consistent top-20 finisher and he'd "won" two training runs.(In downhill, training runs are timed and used to determine start order.) Friedman finished the season as the 27th-ranked downhiller in the world—and iced the cake by winning the U.S. National Championships in Alaska by two full seconds over his No. 2 ranked teammate, Daron Rahlves.

"He's got a really nice, light touch," says McBride of Friedman. "He's gonna do great stuff."

As of early January 2005, Friedman had started his season with anything but a "light touch," scoring an amazing seventh place at Beaver Creek—just behind his teammates Bode Miller and Rahlves, who finished first and second. Ski Racing magazine called it "the greatest day in U.S. downhill history."

"Freedog's charging," said McBride.

But if there's one certainty about downhill racing, it's that things happen fast, for better and for worse. Just ask Mac.

THEY ALL LOOK FAST ON TELEVISION. BUT THE CAMERA LIES: It flattens the slope and slows the racers until they look like they're just schussing easily down a wide, gentle slope. It might surprise you, then, to stand beside the downhill course at Beaver Creek, on a run called Golden Eagle, and watch the racers fly past.

The hill is steep; its double-black-diamond rating means it is terrain for experts. Without skis, you can barely stand up. Most skiers would take slow, careful turns here—but downhillers don't turn so much as careen, or maybe plummet, with nothing but a double layer of orange safety netting between them and the emergency room.

A minute apart, each racer comes screaming into the top of the chute, announcing his arrival with a little plume of snow that hangs in the sunlight for a moment as the tiny, brightly colored figure shoots across the slope and plunges down the fall line, accelerating past the point of no return. In seconds they're past us, topping 70 miles per hour, skis chattering harshly on the ice {the course is watered at night, so it freezes like a skating rink). One more big, sweeping turn takes them down onto the flats, then around a clump of evergreen trees and soaring off a jump. Then they are gone. And you realize that this isn't skiing as you've ever conceived it; this is Formula One racing, without the cars.

THEY MET DURING MAC'S FRESHMAN FALL, IN 1997, WHEN Friedman visited as a prospective student. They hailed from opposite corners of the country—Macartney from suburban Seattle, Friedman originally from Atlanta, though his family later moved to Park City, Utah. They'd bumped into each other on the skiracing circuit, each trying to make a name for himself and hoping to be chosen for the U.S. Ski Team, an elite crew of 23 racers.

As a teenager Macartney had dreamed of attending Dartmouth, though he'd never even visited Hanover. All he knew was that the school had lots of snow and good academics, and the ski team was pretty decent, in case the U.S. team didn't work out for him. He applied early decision, sight unseen, and was accepted. "I just decided to go for it," he says, displaying the sort of hell-bent attitude you'd expect from someone who takes Golden Eagle without really turning.

Friedman was a little less certain. He visited on a Friday night, and Macartney took him out, sneaking into fraternity parties through fire-escape windows, and staying up very, very late. Sold.

"I'll never forget that night," Friedman says, though he's a little vague on the details—something about a "Disco Inferno" party and a woozy ride back to Logan Airport in Boston the next day, with his father peppering him with questions.

Since then the downhill duo has spent every spring term at Dartmouth, Macartney majoring in economics and Friedman in history. The rest of the year, June through late March, belongs to the ski team.

Life on the road with the team resembles a cross between a hard-core ski trip and a roving frat party. In New Zealand, where the team trained at Treble Cone ski area, near Queenstown, the routine was always the same: up at 6, on the hill by 7:30, before the lifts opened. They'd ski hard all morning, running a couple of different courses; in the afternoon they'd face a couple more hours of grueling "dryland" training, such as playing soccer, lifting weights or going through an excruciating "core" strength workout (to get a taste of this, try doing sit-ups with someone pressing down on your chest).

They're as hard on their equipment as they are on their bodies. One morning Macartney crashed and broke a pair of Super G skis. He went to the base and replaced them (his ski sponsor, Salomon, gives him several pairs for the season). In the afternoon he skidded out of a giant slalom course and broke the second pair.

In the evenings they retire to their rooms to read, watch movies or check e-mail from home. Friedman can usually be found strumming his guitar; he takes it everywhere he goes and has played a few coffeehouse gigs in Europe. With his curly brown hair, he resembles—vaguely—a beefed-up Bob Dylan.

Every few days the boys need to blow off steam with a night on the town. One such evening they stumbled into the last open bar in the small town of Wanaka, only to find the entire coaching staff already there, up to their eyeballs in Steinlager, the local beer. (The skiers prefer Red Bull and vodka.) I wound up playing quarters, for the first time in 15 years, with Friedman and Macartney. The next day I spent most of my 30-hour trip home thinking about what a mistake that had been.

LAST MAY FRIEDMAN AND MACARTNEY WERE STRESSING OUT. It was the last week of classes and both were scrambling to finish out their last Dartmouth term. In a few weeks they'd have to face the graduate's ultimate question: "Now what am I going to do?"

In Macartneys case, the answer was easy: Ski for the U.S. team. But that also meant going home to live with his parents. "I'm 26 years old and I'll be living at home," he moaned. "It sucks." But he had no other choice, since his earnings—from sponsorships and ski contracts—barely covered two terms of Dartmouth tuition (with a little left over for Red Bull-and-vodkas). While his teammate Miller recently signed a $2 millionski deal with Atomic, Macartney scrapes by. "I didn't even have to pay taxes last year," he says.

Friedman still lives in Park City, where he rents a place of his own, but he has financial struggles, too. The ski team doesn't pay either athlete; they rely on sponsors. Sometimes they have to buy their own plane tickets to Europe. Last year Friedman and a teammate held a fundraiser to help cover their expenses, which didn't please the ski team's P.R. office very much.

This year is crucial for both athletes, especially Macartney. He needs to keep his body whole so' he can regain his former confidence. "Once you've been injured, it's hard to get back on the horse," says Coach McBride. "But Freedog has shown he can perform at the World Cup level, and Mac hasn't done that yet. Time is definitely not on his side. He's gonna have to perform this year."

Back in May, though, Macartney seemed more worried about how he was going to perform a tricky regression analysis for one of his economics classes. He tried not to think about it too much as he tucked into a steak and sipped a beer at the Hanover Inn. In fact, although Hanover spring was blossoming all around him and the air was balmy and graduation finally within reach, all he could think about was next winter. "I can't wait for this season," he said. "I feel like I've just scraped the surface of my potential.

As of January Mac had scored a few points in the World Cup but still wasn't skiing the way he felt he could. In an e-mail from Europe, he wrote, "I'll be right in there for four of five sections [of a course], then have one where I make a big mistake and finish out of the points."

Freedog was having the career-making season. After Beaver Creek he'd finished seventh again at Val Gardena—this time beating his elders, Miller and Rahlves, who tied for 14th. Then, on January 5, during a training run at Chamonix—the same course where he had won his first top-10 placing a yean earlier—Friedman lost his balance on a bump and careened out of control, sliding right past McBride at more than 50 miles per hour on his way into the safety nets.

McBride dashed down the hill and found, to his relief, that Friedman was still conscious, though he'd cut his face. He had, however, broken both bones in his lower right leg as well as several bones in his left hand, and McBride knew his young star's season was over. The course medics stabilized him, and it was Friedman's turn to take a helicopter ride.

EDITOR'S NOTE: After breaking his leg, Friedman suffered a complication known as "compartment syndrome," requiringsurgery; he was kept in intensive care for several days, and is now recovering at home in Park City."It's always hard to see one of the boys get injured badly, and it's especially ablow to the team, as he has been skiing so well, "saysMcBride. "I am sure he'llbe back next year, but he has some nasty injuries to his lower leg and will probably need a few surgeries to make sure everything is A-okay."

Two of a Kind Macartney (left) helped convince Friedman (right) to attend Dartmouth, where the duo bonded on and off the slopes.

AT THE TOP LEVEL OF SPORT, FRIENDSHIP MATTERS A LOT LESS THAN RESULTS.

BILL GIFFORD, now a correspondent for Outside magazine, says hewas possibly the worst development-team skier in Dartmouth history. Heis working on a biography of John Ledyard, class of 1776.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

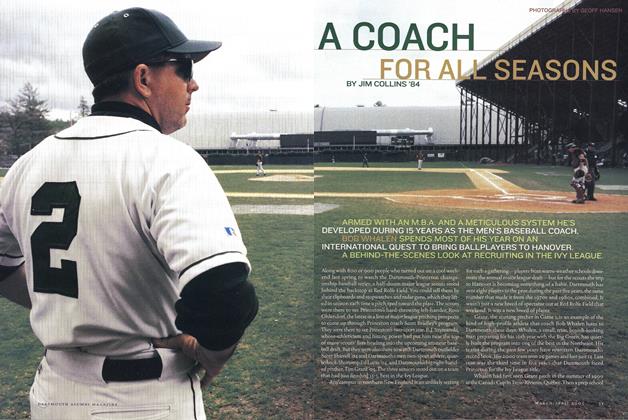

Cover StoryA Coach For All Seasons

March | April 2005 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

Feature

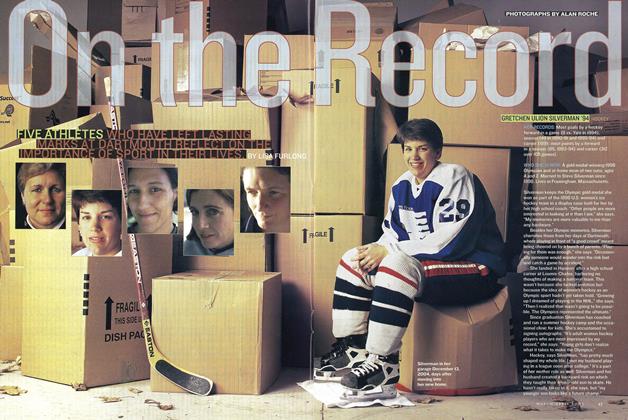

FeatureOn the Record

March | April 2005 By LISA FURLONG -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

March | April 2005 By THOMAS AMES JR. '74 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

March | April 2005 By Gray Mercer '83 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYOut of Control

March | April 2005 By Lance Roberts ’66 -

NEWS ANALYSIS

NEWS ANALYSISFraming the Letter

March | April 2005 By Brad Parks ’96

BILL GIFFORD ’88

Features

-

Feature

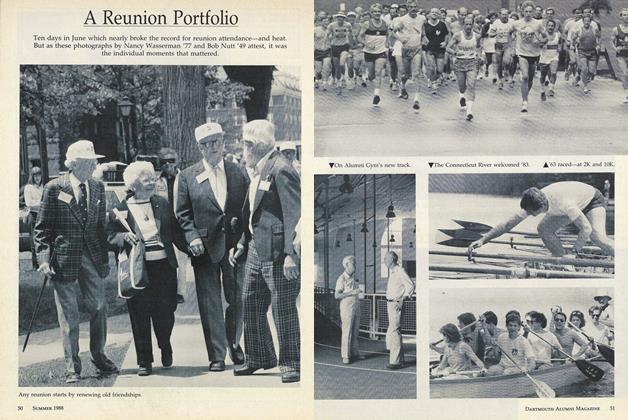

FeatureA Reunion Portfolio

June • 1988 -

Feature

FeatureTwelve Hours and Their Aftermath: The Student Seizure of Parkhurst Hall

JUNE 1969 By C.E.W. -

Feature

FeatureSon of Animal House

SEPTEMBER 1989 By Ed. -

Feature

FeatureOh Behave!

July/August 2012 By Julie Sloane ’99 -

Cover Story

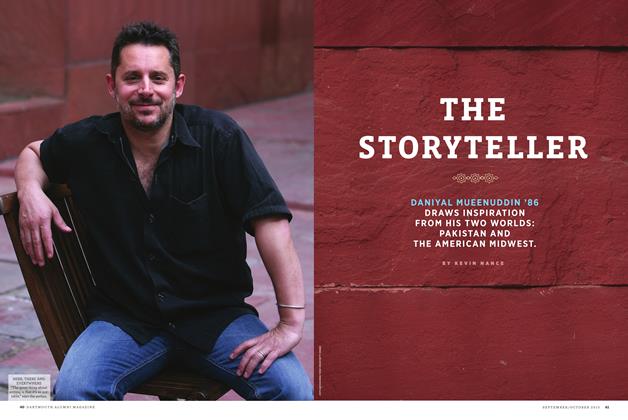

Cover StoryThe Storyteller

September | October 2013 By KEVIN NANCE -

FEATURES

FEATURESThe Class of Covid-19

MAY | JUNE 2021 By Svati Kirsten Narula ’13